As an amateur scholar and die-hard enthusiast of everything to do with Alice in Wonderland, I have launched a podcast that takes on Alice’s everlasting influence on pop culture. As an author who draws on Lewis Carroll’s iconic masterpiece for my Looking Glass Wars universe, I’m well acquainted with the process of dipping into Wonderland for inspiration.

The journey has brought me into contact with a fantastic community of artists and creators from all walks of life—and this podcast will be the platform where we come together to answer the fascinating question: “What is it about Alice?”

For this episode, it was my great pleasure to have Arnold Hirshon join me as my guest on this episode! Read on to explore our conversation and check out the whole series on your favorite podcasting platform to listen to the full interview.

Frank Beddor

Thanks a lot for being on the show. I’m chatting with Arnold Hirshon, who’s the president of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America. I'm really interested in the Lewis Carroll Society. I wrote The Looking Glass Wars books and part of my metafiction was some confrontations with Lewis Carroll Society members. When I was first publishing my book in the UK, I was invited on the BBC to talk about Alice and why I decided to write it. There was a little controversy because I'm an American rewriting it and it was even worse that I was a movie producer. So when I got on the show, there were all these Lewis Carroll Society members protesting and they had placards with “Off with Frank Beddor’s Head!” I thought, “Oh, my God, I'm going to be interviewing the president of the Lewis Carroll Society, I got to give that story up to start.”

Arnold Hirshon

Was that the UK society or was that the North American?

FB

I didn't know there were multiple societies. Maybe you could start by filling our listeners in on the various societies and how the North American Society was formed and your involvement and what the mandate is.

AH

The Lewis Carroll Society of North America, the one I'm President of, started 50 years ago. The basic purpose is to advance the study and interest in any of the works by Lewis Carroll, the mathematical works, logical works, games, puzzles, and of course, the Alice books, The Hunting of the Snark, Phantasmagoria, anything. And it could be any aspect. It can be the literature itself, it can be illustration, music, movies, plays, the whole gamut. All of that is part of our remit. The Lewis Carroll Society in the UK, which is known as the Lewis Carroll Society, continues to do its work, There are also societies in Brazil, the Netherlands, and Japan, and we're all loosely affiliated in our interest. But ours, the North America society, is probably the one with the greatest reach and the most international membership. About 10-15%, 20% of our members are actually outside of North America.

FB

What do the members do in terms of interacting with all of this work? Because it's obviously so deep-seated in pop culture, I imagine you could spend your life studying and trying to keep up with it and not even scratch the surface. What are the members mostly interested in?

AH

It’s a combination of things. We have a journal that comes out two times a year, the Knight Letter, which is pretty extensive. It is everything from scholarly articles to fun facts and the latest occurrences found in popular culture, whether it's a political cartoon or a quote. It includes information about newly published editions, illustrated editions typically, anywhere in the world. That’s one element of our educational programming.

We also run two conferences per year, one virtual, and one in person. The last one was in Cleveland this past September and we're looking to hold another one in the fall of 2024 as a celebration of our 50th anniversary. Those topics can be a very wide range. This last time, there were people discussing Alice in popular music and rock music. We had people discussing Alice in dance, Alice in literature, Alice in Japan. So those conferences tend to be a fairly wide gamut. Then we run typically about eight to 10 virtual programs throughout the year which could be an illustrator discussing a work in progress, or a recently published book. It can be Alice in the movies. Those, again, run that whole range and it is not just Alice-related. We also have collectors talking about their collections and latest acquisitions.

FB

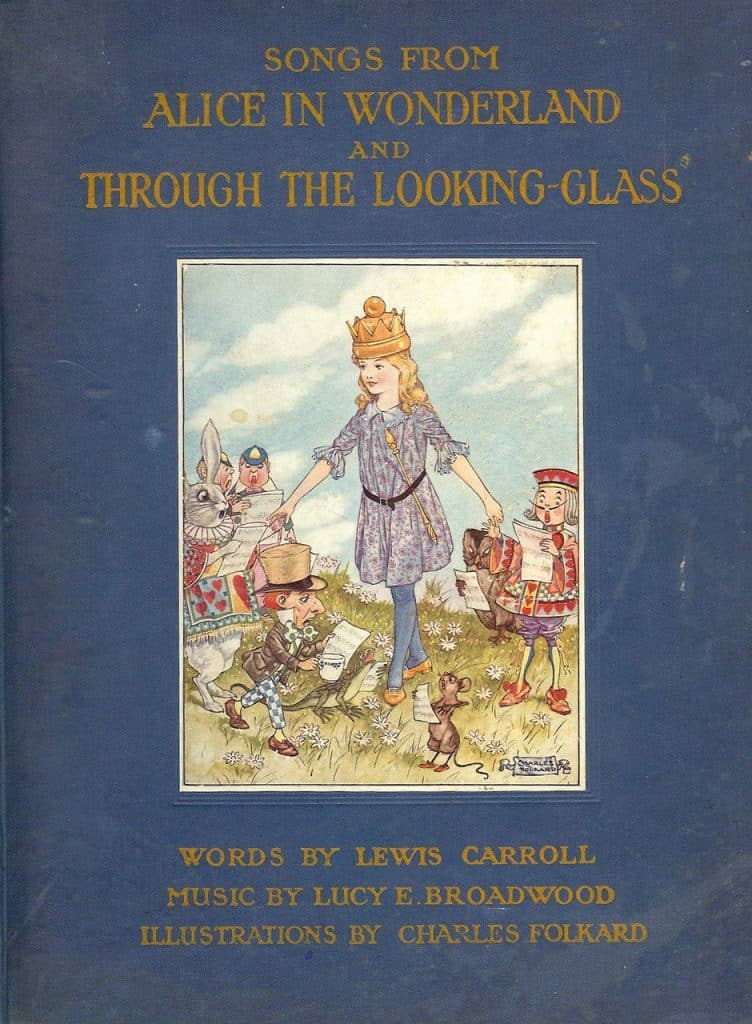

That seems like it would be a big section of the membership because there is so much to collect. There are so many interesting books. I have a book, Songs from Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.

AH

Yes, absolutely. I know it well.

FB

I was fascinated with the lyrics. It was published in 1921. The art is amazing.

AH

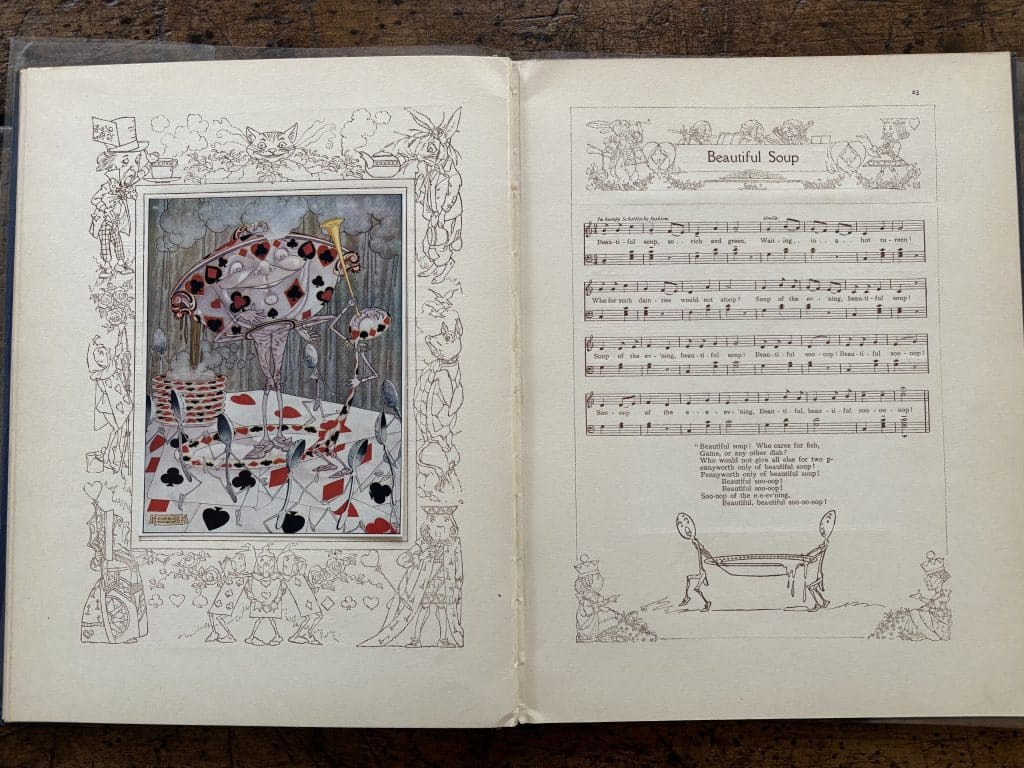

I have a copy of it sitting over there on my shelves. I actually have both that version, which is the original, as well as a couple of reprinted versions. There's a delightful illustration of Beautiful Soup in that book, the Soup Bowl has this long pair of legs.

FB

Yes, I love that image. Love it.

AH

Charles Folkard is a brilliant illustrator. I also have the original sheet music of two of the three Alice in Wonderland songs that Irving Berlin composed in the early 20th century. There’s a whole wide range of things. I was an English major in college so my interest started from the literature side, from the text. But more and more it gravitated towards the illustrations. The Alice books in particular are, by far, the most illustrated books of fiction in the world.

FB

There are so many remarkable facts. It’s the second-most quoted literary work in the world behind the Bible. There are more translations than Harry Potter. I think it's 175 or 190 countries. I didn't know there were that many countries.

AH

Sometimes it can be two or three dialects from the same country. It could be Catalan, in Spain, as well as in Spanish. There are also multiple dialects in Chinese.

FB

Is there somebody that collects everything that's coming out so you have an archive? You brought up political cartoons and during the Trump administration, there was a massive use of Alice in Wonderland to describe the functionality of the government. “Down the rabbit hole” “Off with your head” and “Through the looking-glass”. Tweedledum and Tweedledee were used. Often to great comedic effect. So does somebody collect those things for your society? Or are they just talked about at these conferences?

AH

It’s all individual collectors. There are some institutions, certainly, that collect but I don't think that any institution by any means has comprehensive collections, meaning exhaustive, what we would call completist. I am not a completist collector. There were hundreds published by the original publisher Macmillan. So you have the first 1,000, the first 2,000, then you have the first 10,000. Some people collect all of those, every single one. I do not. If I have one good copy of Tenniel, it's enough, because I use my collection for research and personal interest. I'm not necessarily trying to collect a perfect copy of a first edition of something. I want representative illustrations from that Illustrator. I want something that I can also afford because some of these things can go literally into the millions of dollars, and many of them will go into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

There are certainly some very major collections in not just the British Library, but also in North America at the University of Texas, New York University, the University of Toronto, Harvard, and the Morgan Library in New York. There are probably about 20 I could rattle off that have significant collections. But very often, they stopped collecting at a certain point, they're not necessarily collecting late 20th century, early 21st century. Because I'm interested in illustration and so many of these illustrators have come out and continue to come out now, trying to keep up with all of the new ones that are coming out is just impossible.

FB

It would be amazing to have an institution that collects everything that they can find in pop culture. My daughter loves Taylor Swift and I recently wrote a blog about her song, “Wonderland” which I did not realize before there was such a thing. Suddenly, I was a very cool dad for 24 hours. There's so much out there and it's really interesting. Visually, it's really interesting, whether it's the album or, as you said, the illustrations or photographs of gardens. There are cartoons I find terrific and it would be great to have the movie posters.

AH

Absolutely, and not just movie posters but there are also pop culture posters from theatrical productions and concerts. So there are people who collect and there are a lot of people who, like me, have a more specialized collection. Some people collect just posters, some collect just sculptures, or even just soft sculptures. So you get this wide variety of people who have very varying interests and we’re all joined together by sharing some element of interest in the works of Lewis Carroll.

FB

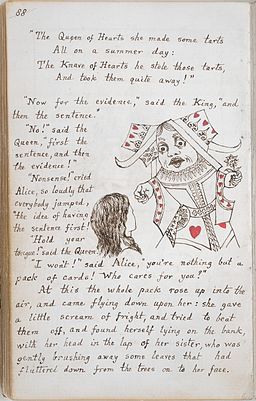

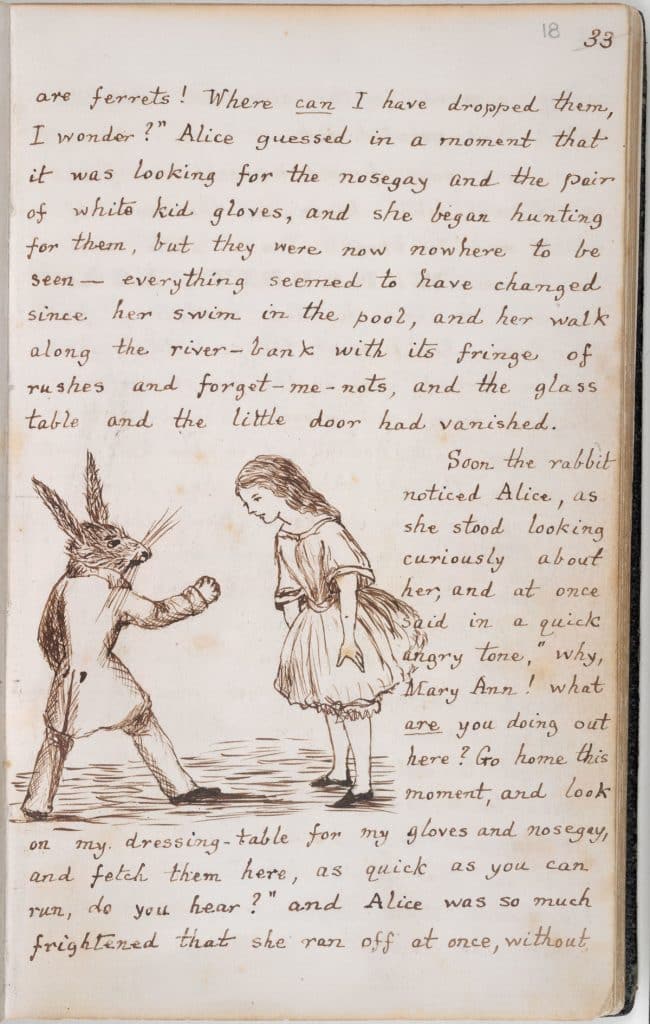

The original manuscript with Lewis Carroll's drawings must be very expensive.

AH

There's only one copy of it. There have been facsimile editions but the original is in the British Library. Unfortunately, the British Library recently had a cyber attack so you cannot currently access it online but they normally have that available online as well. On the very last page, there was a photograph of Alice Liddell and an oval-sized picture of her and underneath that, he had originally drawn a picture of her. For decades, people had no idea the drawing existed but they finally realized it so now you can see both the original drawing and the picture of six-year-old Alice.

FB

So the listeners realize the book was originally titled Alice's Adventures Underground and that's the book we're speaking of. Is it a book that you can just touch there? I imagine not.

AH

Somebody would have to have a lot of scholarly credentials.

FB

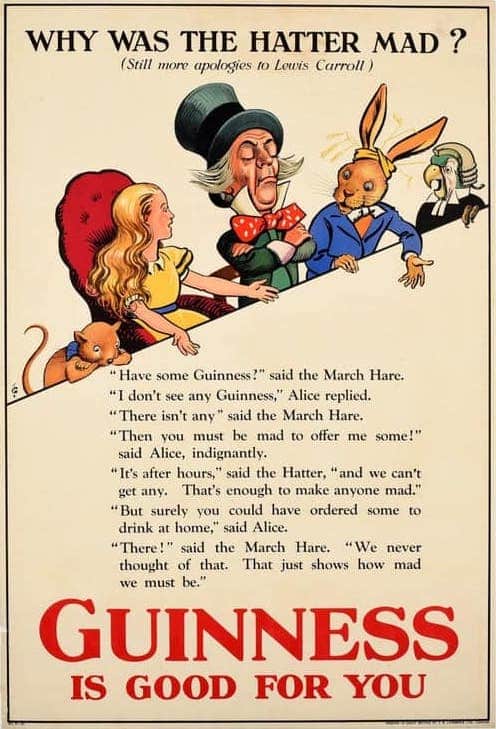

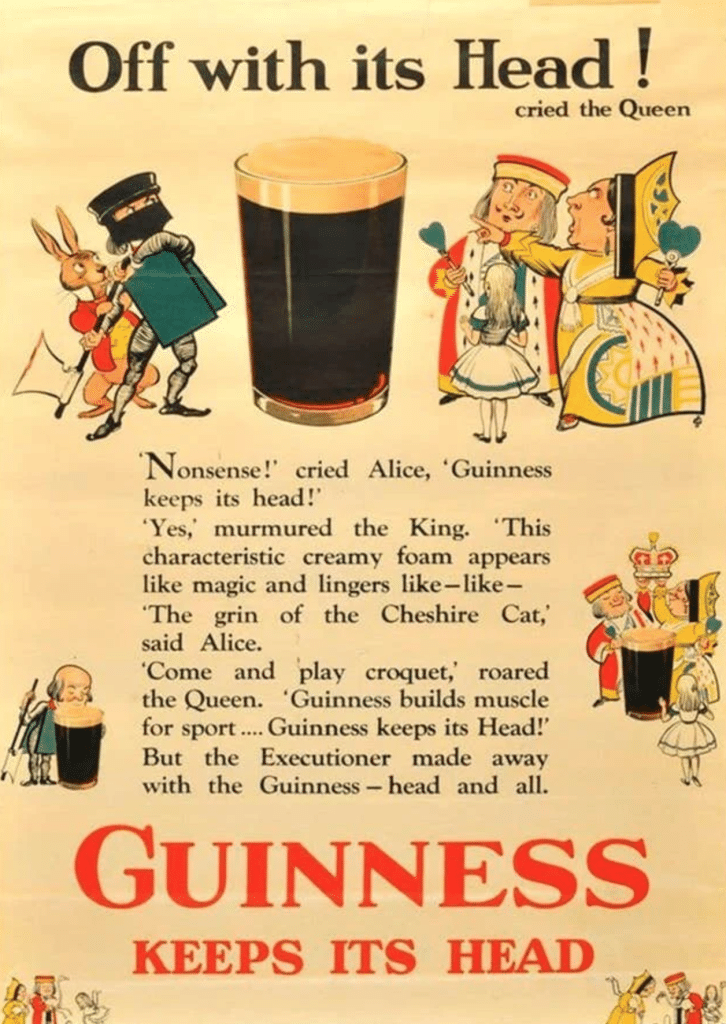

I’m very interested in doing a documentary about Alice, not so much about how deep Alice runs in pop culture, but why Alice is a muse for so many artists like Taylor Swift and the Wachowskis who did The Matrix and using that to bring people into this deeper Lewis Carroll world. Show them things like the Guinness beer ads, which used Alice for years and years and years.

Why does Alice last? What is it about Alice that inspires us to keep reinventing her to reflect our contemporary world?

AH

Just on the Guinness point, those ads were being used to promote the health benefits of beer. They were sending these things to doctors. When it started in the 1930s and through the 1960s, they were using Alice because everybody would know what the cultural reference was.

But Alice herself is essentially a cipher. Alice is not the main character, all the other characters are the main. All these things are getting absorbed through Alice and she's learning as she's going along. She makes for the perfect foil for any number of characters who come into her life and then leave her life in the next episode, which is essentially usually the next chapter. But there are so many ways of interpreting so much of the text. There are so many ways of visually representing Alice. For example, the Disney character is, to some people, more common than the Tenniel version of it. They have no idea that Disney's was not the first movie, that there had been 50 years of Alice movie-making before Disney showed up on the scene. And he would have done it himself earlier, but he dropped the project and picked it up later. So there are all of those threads that keep coming through.

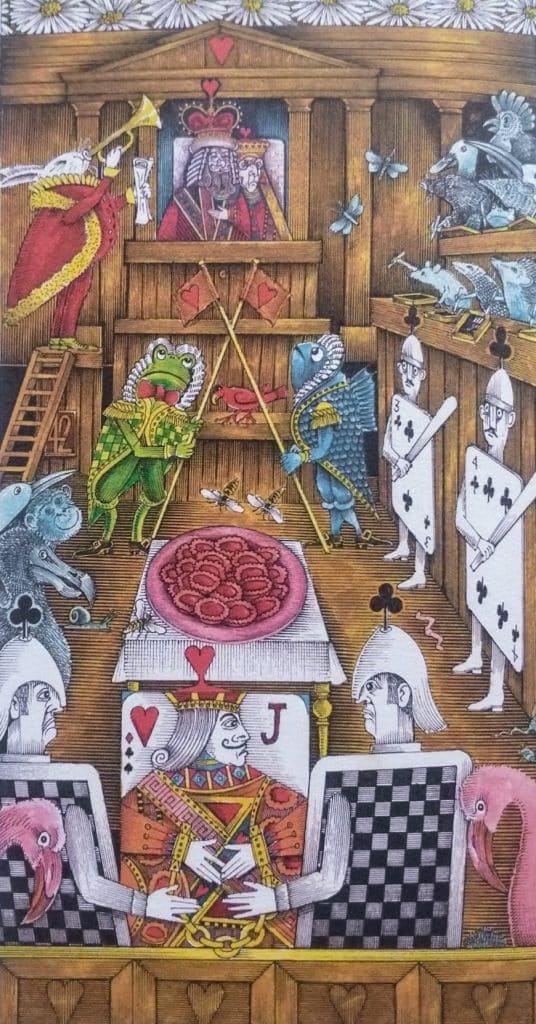

There's so much ambiguity in the story. The scenes are not plotted out in any strict order. You could move the chapters in a different order, not so much in Through the Looking-glass but certainly in Wonderland, you could change the order if you were reading it to a child who never had read the books before. Except for the very beginning and the very end, the child would have no idea what order you're reading them in, because there's no logical sequence to it. There's no description of the backgrounds. There's no description of most of the things on the table in the Mad Tea Party, they're not mentioned at all. So that gives, whether it's a filmmaker or whether it's an illustrator, license to make it up as they go along.

FB

To your point, until Tim Burton came along all the other adaptations have had the flaw of being episodic and trying to give agency to Alice. One of the reasons I wrote my novels was to give her that agency. She meets Lewis Carroll who doesn't believe her story but ultimately, she is destined, and ultimately, it's her agency. Then she moves through enough of a plot that it feels more contemporary. There was more agency in The Wizard of Oz for Dorothy than for Alice because Dorothy had a very specific goal and there were obstacles along the way, and those obstacles became friends and then they helped her in the end. What you're saying is that as a cipher, Alice affords creators so many choices with the other characters. That's probably a really strong reason why she's such an amazing muse for so many creators.

AH

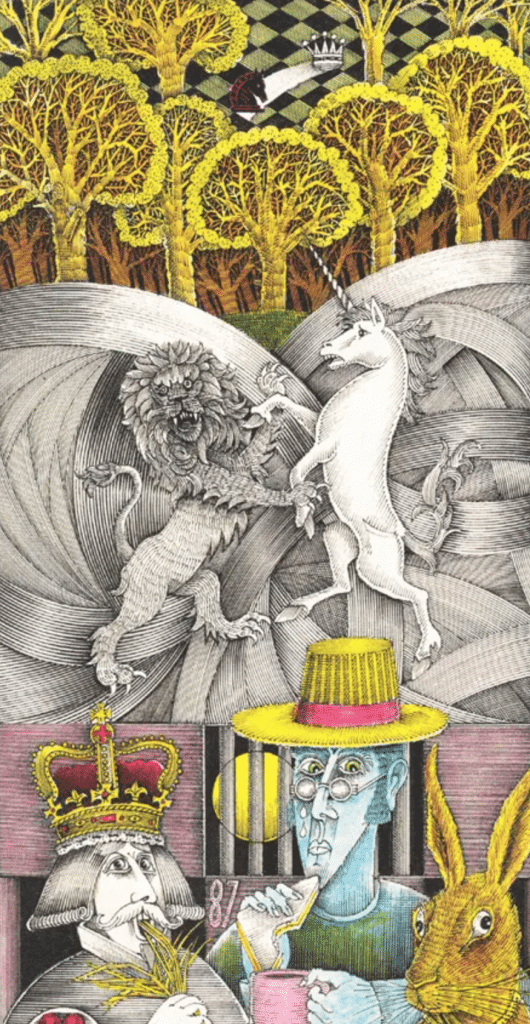

That’s the difference also between Wonderland and Looking-glass. I've often described Wonderland as a vertical tale. Alice falls down a rabbit hole and then proceeds through things without any rhyme or reason. Her conversation with the Cheshire Cat, “Where should I go?” “If you don’t know where you're going, any road will take you there.” Whereas Looking-glass is a very horizontal tale. Alice has an objective, she wants to get from one end of the chessboard to the other end of the chessboard so she can be crowned queen. Along the way, she's going to meet people who she hopes will help her along the way and most of them in Looking-glass do help her whereas in Wonderland, many of them don't care. Hatter and the March Hare, they're living their own life so they're not going to do very much to help. Some of the Looking-glass ones don't either. Tweedledum and Tweedledee are not the most helpful characters in the world.

FB

I think that is very helpful in terms of breaking down the two books. It seems that there are two camps. There's the whimsical fantasy dream aspect of the texts that people take away and then there is the surreal nightmare in the illogical and self-inflicted insanity that happens in the book. Do you fall into either of those camps? Or, as a scholar, is there another camp that you look at the works from?

AH

It’s an interesting question. I think the difference that you're speaking to is, in part, is this an adult book for adults?” Or is this a book for children? The first part of what you said to me is more the children's book, which can be appreciated by children at a certain level. But even in Victorian times, there were going to be any number of references in the text that no child was going to really pick up on. To me, the books are, in essence, adult tales. To really appreciate the text, you do need to be an adult not just to understand the cultural references of Carroll's time, but to understand the life experiences. When I was a university administrator I would say to people, “Just read Alice in Wonderland and you'll know everything you need to know about management.” Every chapter will teach you, and sometimes every paragraph will teach you something that you need to know about how to manage in a situation - how to get yourself extricated, how to deal with conflict management. I probably lean more towards your second category than I do towards the first for that reason.

Many, many years ago I read that one needs to read Cervantes’ Don Quixote as a teen, as a young adult, and in old age, because you will understand and read things into it and see things differently at different ages in your life. I think the Alice books are very much like that. You come to appreciate different things and even those of us who have read the texts many times, and can recite whole passages, will still reread it or reread a chapter or reread one of the poems and see something that we never saw before. There's so much to distill in every one of those chapters and in each one of the poems. That's why it's such a brilliant work. It's also one of the things that I think separates it from The Wizard of Oz.

FB

I agree with that. I read it to my daughter when she was eight or nine and she thought it was very funny and weird. But during Lewis Carroll's time, there weren’t all the categories of publishing that we have now. He wasn't writing for middle grade or YA. So who was he writing for? It's very satirical of the Victorian era and he referenced the government a lot. He makes fun of the emphasis on memorization in education, but he was telling the story to these young kids. What do you think he was thinking in terms of how his audience was gonna react?

AH

Originally, he had an audience of Alice and her sisters, and himself. He was writing this to amuse them but also himself. So he was not really thinking about publishing it when he first told the tales. Alice Liddell was amused by the stories and she asked him to write them down so he wrote them down and illustrated them. Originally, I think he thought, “That's it, I'm done.” But then other people read it and said, “You really should publish this.”

Of course, one of the key elements of the Alice books is they were the first books that did not speak down to children. They were not moralistic tales. This was “Adventures” in Wonderland. I think that was intentional. I think that's what he was after for his audience, to speak to children as if they are young adults, not to speak to children as if they are little children. Whether Alice herself reread the books later in life and saw things we probably don't know. But I think that certainly other people, and generations of people, have. I have a granddaughter who's five years old and I brought her a copy. She can look through the pictures. It's the classic, “What's the use of a book without pictures?” I was giving her the five-minute version for a five-year-old. But after I left, her parents told me she went back to the book and she was spending a long time looking at the pictures. Every audience will appreciate it looking for different things.

FB

I started with a pop-up book. I think it was the first pop-up book my daughter had ever seen. Any way to engage kids visually and then synopsize the story and use your voice because those things stick with them. Then they'll come back to it, as you suggested, later in life.

I know that you're the son of a photographer and your kids, one’s an editor and one’s an illustrator.

AH

I am the son of a photographer. My son Daniel is a film editor and photographer who actually published an Alice street photography book, Alice in Manhattan: A Photographic Trip Down New York City’s Rabbit Holes, which uses his own photography with quotes from Alice.

My other son, Michael is an illustrator and a professor of Illustration at the University of Utah.

FB

That’s where I went to school. That’s wonderful for both of your sons.

So you would be well equipped to share with listeners Lewis Carroll and his early photography, which would be considered cutting edge by today's standards compared to where the art of photography was when he first started. I don't know if many people realize that he took photos of Alice Liddell and some of her sisters and he also had a lot of interesting techniques with his photography.

AH

In the days when he was doing photography, the subjects had to sit very still for a longer period of time just for the exposure to be able to take. So he used to costume more girls, girls and boys, and adults, as well. It was very heavily portraiture, but he would enact scenes. There's a picture of Alice in a beggar costume. He would have these typically painted backdrops that he would use. He had pictures of people who were prominent at the time. Ellen Terry was an actress, for example, that he photographed. He experimented quite a bit and then when he lost interest, he just dropped it entirely. Probably around the 1880s, he just stopped doing photography entirely.

FB

Will Brooker, the author of Alice's Adventures: Lewis Carroll in Popular Culture, which is a terrific book, has that Alice as a beggar photograph you mentioned on the cover. It’s a remarkable photograph given when it was taken. It’s so vibrant and she comes to life.

AH

His composition was excellent. He knew exactly how to pose whoever he was taking the photograph of. Sometimes it would be two or three children, for example, in the same picture and he would very elegantly pose mis-en-scenes for his audience and that audience was typically the family. He was not setting up a shop. He wasn’t a portrait photographer by trade. Nor was he trying to sell these as works of art. If you try and buy them now, they're expensive works, but, at the time, he was doing this basically for his own enjoyment.

FB

So far in our conversation, we have only referenced him by his pen name, Lewis Carroll, and not his actual name, Charles Dodgson. In your experience in terms of randomly speaking with folks about Lewis Carroll, do people know Charles Dodgson?

AH

Probably not. Unless I'm speaking with a mathematician or logician, probably not. Most people who know Carroll’s work reasonably well have some knowledge of him. If you said the name, they would probably recognize it, but not necessarily make the immediate association.

FB

Interestingly, his real name has not become more prominent with all of the outlets out there. It's always been Lewis Carroll. Because, in my conversations, nobody seems to know who Charles Dodgson is unless they're a big fan of his.

AH

Right. That was intentional on his part as he wanted to keep his professional life as an Oxford don teaching mathematics and logic, separate from his creative, fictional characters. Especially once Alice came out, people started to know that this Oxford don was Lewis Carroll. But he continued to publish the books under a pseudonym. He had two parts of his life and he wanted to keep them separate.

FB

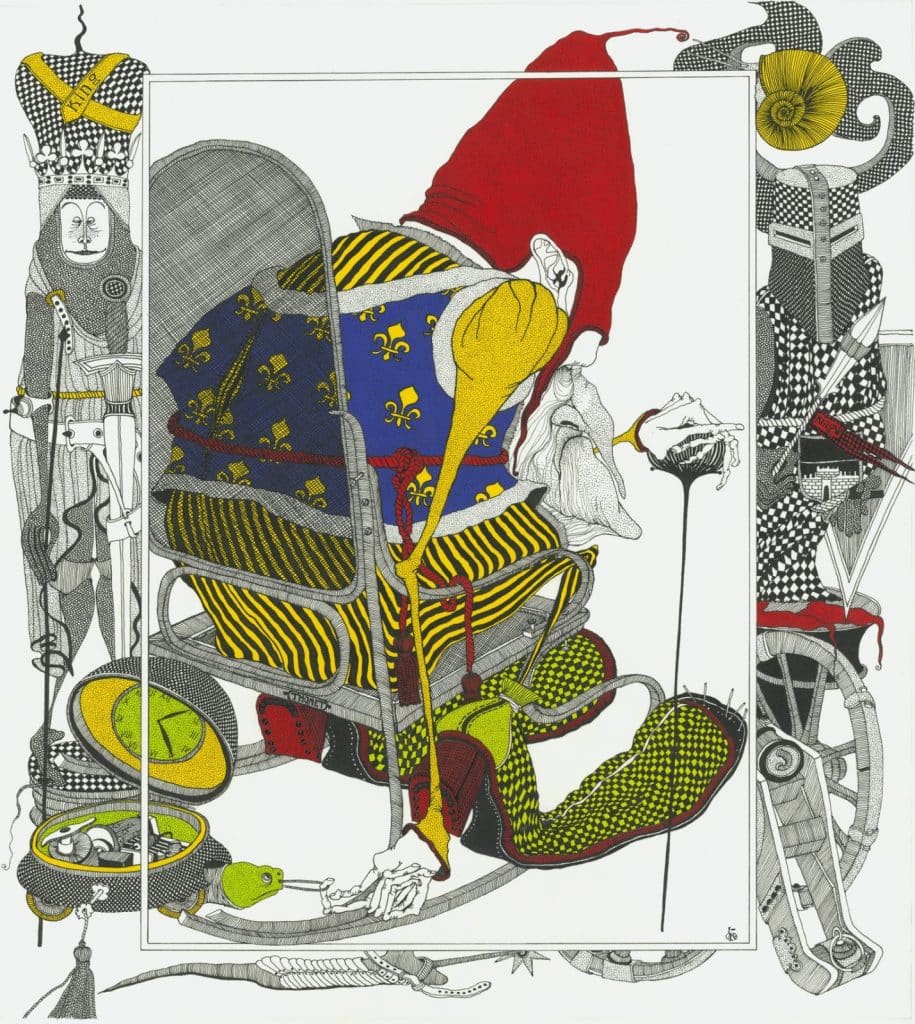

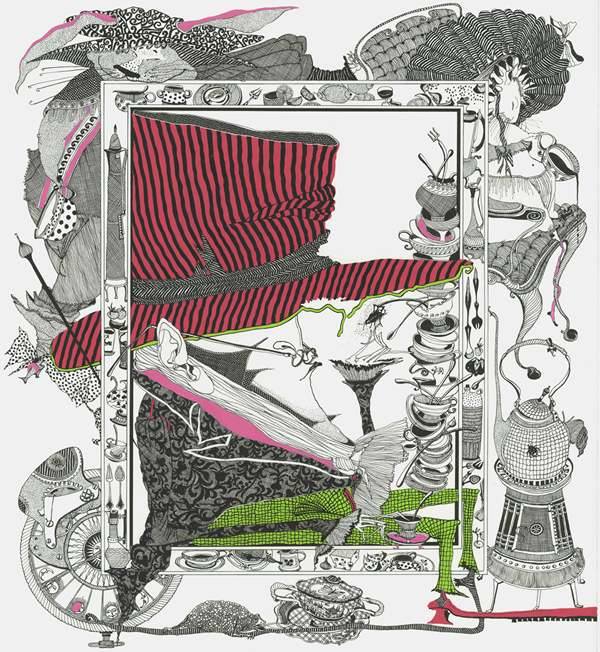

If you had to choose one illustrated book of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and that's all you could have in that big library of yours, which one would you pick? Mine is Ralph Steadman’s take on Alice. I absolutely love Ralph Steadman. It's the lines, the contemporary 60s vibe. It's not a surreal nightmare, it’s a surreal world. I just absolutely love his Alice book. How about you?

AH

I was afraid you were gonna ask this question.

FB

I thought, “Oh he's a scholar. Let's break it up a little bit.”

AH

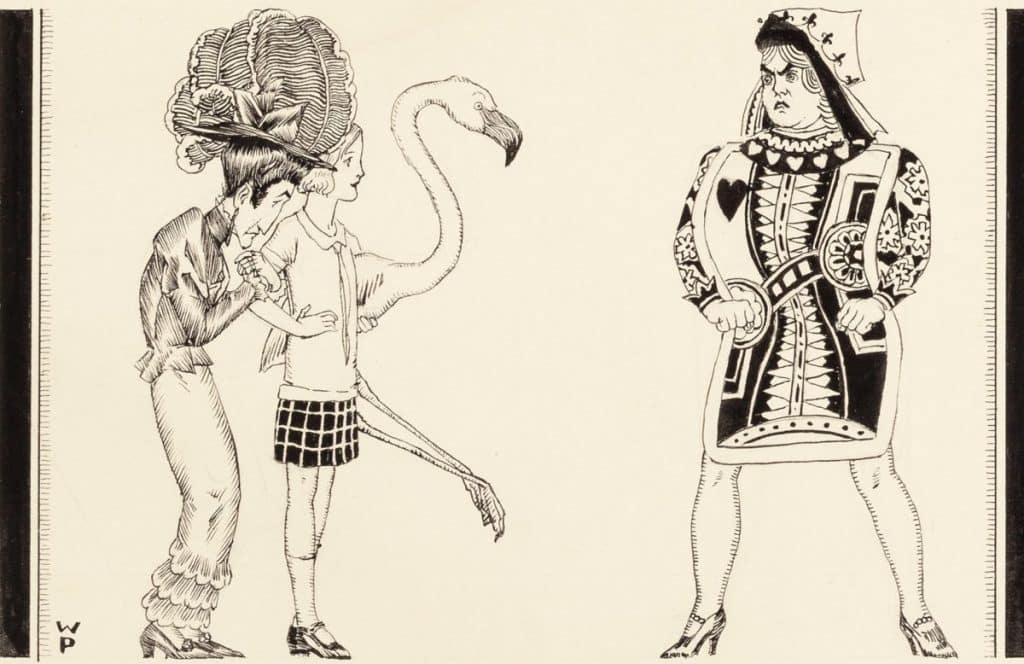

It’s not an easy choice. I do love Steadman’s illustrations. I love Barry Moser's. I love John Vernon Lord’s illustrations. Jean-Jacques Sempe, who most people know from his New Yorker covers, published an edition in French in 1961 that is just delightful. They're all brilliant. If I had to pick one, Willy Pogany was an illustrator in the early to mid-20th century. In 1929 he did a flapper Alice and it is absolutely delightful. It's just brilliant work. One of the reasons I like it so much is when I started collecting and I was leaving one of my places of employment to take another job, the Pogany edition was given to me as a going away gift, and I always treasured it.

There were multiple editions published at the same time. There was a deluxe edition and there was a trade edition. One of the things that's different about the trade edition, the deluxe edition does not have this, ironically, is there are colored end papers. The rest of the book is all black and white line drawings but the endpapers are this montage, this collage of different scenes, all in color. There’s just so much to look at. There are so many things that he was the first to do. That’s really one of the things I look at in my scholarly interest. Who was the first illustrator who did something different?

We've mentioned Alice falling down the rabbit hole a few times. Carroll, in his manuscript, has no picture of Alice falling down the rabbit hole. John Tenniel has no illustration of Alice falling down the rabbit hole. It's not until one of the early American pirated editions that somebody actually illustrates that scene. But everybody is sure they've seen it before and in fact, you haven't because before that showed up in 1898. Those are the sorts of things that I look for. Sometimes it's in the detail. It's one of the things I like about John Vernon Lord’s illustrations; there's just so much to look at in his work. There's a 21st century Russian illustrator, Ksenia Lavrova, who is absolutely brilliant. It's hard to come by her editions in the United States, you have to order them from abroad. I actually picked it up in Russia on a trip a while ago, but the color illustrations and the level of detail, you could sit for an hour looking at one illustration and not see at all. That's how brilliant it is.

FB

That's terrific. Well, definitely going to check that out and the edition with Alice as a flapper.

You mentioned Barry Moser as well. I think he won an award for his Alice book in the 1980s. It seems that every generation reinterprets Alice. In the 1960s there were psychedelic aspects because of the Beatles and the Jefferson Airplane song, “White Rabbit”. In the 1990s there's the whole tech side of it with The Matrix. What do you attribute that to? This re-purposing of Alice to reflect day-to-day life?

AH

It's the movement of the illustrator and using themselves, as well as introducing something generational. For example, how does fashion change? If I'm looking at a Tenniel illustration in the 21st century, these fashions don't mean anything to anybody, right? Pogany’s work in the 20s, the bobbed hair and the flapper dress, and those sorts of things would be very different for that generation. Some of it is speaking to cultural reference in fashion, in the backgrounds, in what's on the table. One of the things I collect are teapots, no relation to the Mad Tea Party, and I've threatened to do a study of just the shapes of teapots in different illustrations.

I think when you start looking at that, that's what starts to tell you why things change. They want to bring something new to it and they want to bring something interesting to it. They want to bring out some elements of the story that nobody had brought out before and they want to do it in a contemporary way. For example, there are an increasing number of graphic novels. We talked a little bit about the translations, but if you look at the illustrations that came out of other countries, the dress can be very different. The portrayal of how the characters look, if you look at a Japanese or Chinese or Russian illustration is very different from a French or German or English illustration, which is very different from an American or a Latin American illustration. So some of why it gets reinterpreted in illustration is to make it relevant to the local culture.

One of the things I've looked at is, which illustrators got republished in a country other than their own, and which ones never did and why did that happen? I don't have a great answer to that. I think in some cases, publishers were looking for what they could republish cheaper, and sometimes the not-very-best illustrations got republished. In Esperanto, it probably doesn't matter what illustrations you use, but in other languages, it does.

FB

It also speaks to why stories last, because they form timeless bridges that connect generations, cultures, and experiences. Alice just happens to work. You mentioned Japan, which I think has the most editions of Alice in Wonderland of any country.

AH

It could be. The Japanese and the Russians each have a very deep interest in Alice, probably for very different reasons. But both have a very strong number of editions.

FB

Stories that are generational and that we hand down, we're sharing a piece of cultural connection for us to somebody else who's then taking it and reinterpreting it for their kid.

AH

Part of it goes to the absurdist surrealistic nature of the books, or at least they've been appropriated by surrealists and absurdists. Each generation thinks it’s the first generation that has dealt with the complexities that it's had to deal with and the topsy-turvy nature of what's going on in its world. That’s why Alice continues to be relevant because it was happening in the Victorian age, it's happening today, and it's happening every decade. If you look at some of the very early films, they're very surreal. That's why I think these things last because you can pull out these elements that are so peculiar but they're timeless.

FB

That's very true how timeless it is and you can interpret it in so many different ways.

I also spoke at one of your events probably eight, or nine years ago in New York and showed my artwork and the various books and graphic novels I was working on. I've hired a lot of different concept artists, mostly people who have worked in Hollywood and it's been really interesting to work with them and see how they interpret the material. They’re looking for something familiar, but they want to make it wholly their own and they certainly want to make it part of The Looking Glass Wars world. But there's always a nod. There's always a little detail for fans of the original books. I'm always looking to do that, even if I've made up all sorts of stories about Lewis Carroll.

I don't know if people know that he had diaries and there are missing pages from his diaries. There's all sorts of speculation about, maybe it had to do with those photographs that he took of young Alice and that the parents were unhappy and things like that. I dismissed that and I said the reason he ripped out those pages is because Alice Liddell was actually Alice Hart from my series and he didn't want people to know that he co-opted her story. Granted, he thought she was traumatized from being on the street as an orphan. So there are little details that I've picked up over the years. I'm not a scholar, but I'm like, “Oh, I could use that. I could repurpose that. That'll be good.”

AH

It’s doubtful he ripped out those pages, by the way, it's more likely that his heirs ripped those pages out of his diaries.

FB

I think Will Brooker wrote about that. He mentioned in his book about Lewis Carroll. Where did those pages go? And what were they about? There was a riff between Alice Liddell and Charles Dodgson over something. I don't know if anyone's figured out what it was about.

AH

The original riff was actually between Alice's mother, Lorina, and Dodson. One of the films that had an interesting take on it was Dreamchild. Wholly fictional, but what a great film.

FB

That really went outside of the books and found a way to tell a story that was edgy and of its era.

AH

And the reenactments of the scenes with her in them with Jim Henson's workshop were just brilliantly done.

FB

There was a photograph of Alice when she was 18, 19, or 20 that Lewis Carroll took, and she looks very unhappy. What’s the story behind that photograph?

AH

I don't know a lot about it. In most Victorian photographs, people look unhappy for a reason. The exposure time was so long that you could not hold a smile for that long. So rather than do that, they just said, “Hold that.” Because if you started with a smile, little by little it was going to go down, it would almost be like the Cheshire Cat smile. You're gonna see it disappear. That's different between the mouth and the eyes.

But the eyes, she did not have the happiest marriage in the world. So whether that might have been part of what's being reflected in that photograph. And of course, for Victorian childhood going into adulthood, there was this kind of heartbreak. You’re not a child anymore, you have to behave in a very certain way. Of course, Carroll was making fun of that in the books but that was very true and that's the way Alice was raised. That would probably also help explain that photograph. She left behind her childhood.

FB

Lewis Carroll gave us a lot of interesting words and terms, obviously, “down the rabbit hole.” He didn't invent rabbit holes, but he made it a portal. Wonderland. I don't believe he invented that either but he certainly invented it as a magical place. “Curiouser and curiouser,” is another phrase. But there are a lot more obscure words that he invented that are in culture today. Why don't you give us a couple of the not-so-well-known ones?

AH

Jabberwocky certainly has quite a lot of those words. Frabjous day. Brillig. Slithy toves. There's hardly anything in that opening verse that he didn't make up. Of course, Humpty Dumpty has to explain what every one of those words mean. If you string along Humpty Dumpty's whole explanation, it still doesn't make any sense. I've tried to do it multiple times. Humpty Dumpty gives this whole long explanation and he explains each word, but it doesn't make a sentence when you get to the end of his description. The vorpal sword is another one.

FB

I've made that into a really great weapon.

AH

There are lots of those things that he either made up or popularized in a way that they wouldn’t otherwise have been without him.

FB

Who was Humpty Dumpty in that 1930s movie? W.C. Fields?

AH

Yes, the 1933 Paramount film. Cary Grant played the Mock Turtle. Gary Cooper was the White Knight.

FB

Okay, so if you were cast in that movie, who would they cast you as?

AH

It would be the White Knight. I love the concept of, “It's my own invention.” In my work life, I would always come up with these off-the-wall solutions and I always felt like, “It's my own invention.” Maybe that makes no sense to anybody else and it's, “Why would we do that?” But I still thought it was a good idea. So I've always associated myself with the White Knight. Carroll associated himself with the White Knight. That’s essentially his self-portrait, not necessarily the illustration, but as a character.

FB

I didn't realize that. I think that is a perfect place to end this very compelling and enjoyable and fun conversation. And your book Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The English Language of the Four Alice Books Published Worldwide, explores the legacy of the four Alice books. Is that available?

AH

We have two editions. There's the Deluxe Edition, which is a two-volume set available to order if you contact jaredx2@gmail.com. We also have the Standard Edition for Volumes One and Two, which are available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

FB

Perfect. I thank you for being on the show and sharing all your insight. Thank you very much for that. I really appreciate it.

AH

Thank you, I appreciate the opportunity to speak with you.

For the latest updates & news about All Things Alice, please read our blog and subscribe to our podcast!