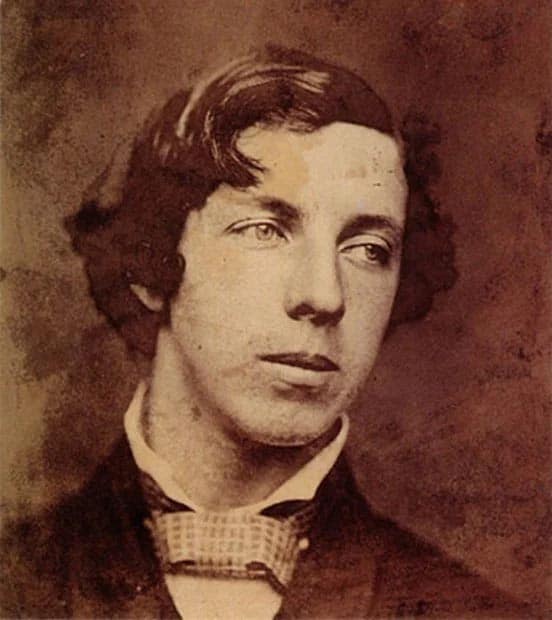

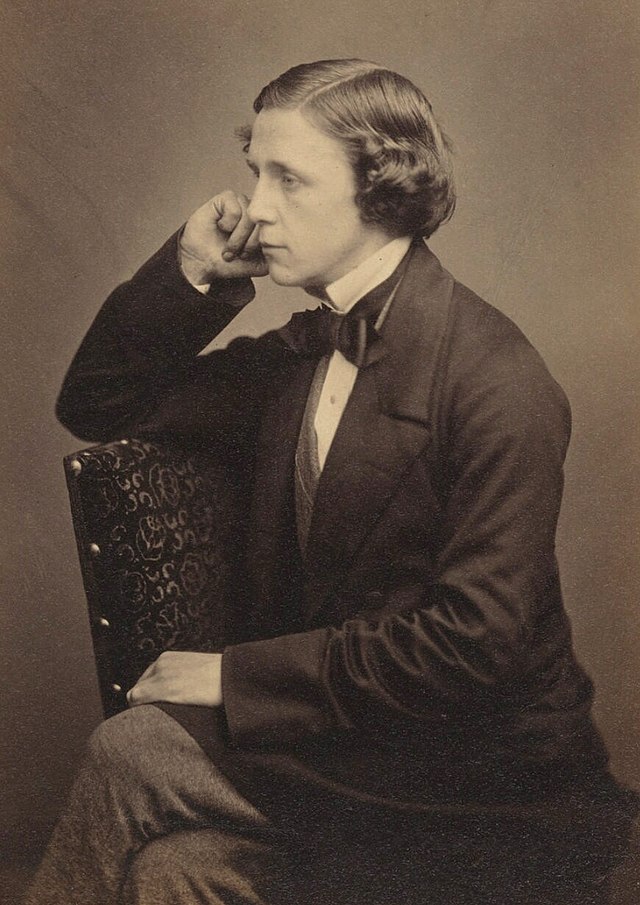

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who gained international fame as Lewis Carroll, was born in Cheshire, England in 1832, the eldest son of a conservative, middle-class Anglican Family. A shy loner with a pronounced stutter, a sufferer of migraines and seizures, he was a precocious, scholastically gifted boy, and success in school came easily to him when he chose to apply himself; the young Charles, it seemed, was prone to distraction, to reverie. Nonetheless, his talents brought him to Oxford University’s Christ Church, where, in 1855, after earning first class honors and a B.A., he was awarded a Mathematical Lectureship. In 1861, he became one of the youngest deacons in the Anglican Church.

By all accounts, Reverend Dodgson was an austere, fastidious man, a puttering, fussy bachelor inclined toward conservatism in politics, religion, and social mores. His daily routines were precisely choreographed and adhered to; he inevitably took the same routes from his rooms in Christ Church’s Tom Quad to lecture halls and back again. He made diagrams of where guests sat when they came to dine with him, noting down what they ate so that the next time these guests visited, he wouldn’t serve them the same dish again. He summarized and catalogued every letter he wrote or received.

Such a man would seem an unlikely candidate to author Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland, whose enchanting nonsense has held the world under its whimsical sway for over 150 years and counting. But the history of imagination is filled with surprising paradoxes, and Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was the greatest paradox of all.

Respected, comfortable, with a small circle of friends, contentment yet eluded the thirty-year-old Oxford Don when, in 1856, Dean Henry Liddell arrived at Christ Church with his family. Until then, a shadow of disappointment had hung over Dodgson’s life—he couldn’t have articulated why—but it began to lift as he befriended the Liddells and their three daughters, Edith, Lorina, and Alice.

Especially Alice, the youngest child, an adoptee.

Dodgson had always been more at ease with children than with adults, but in Alyss’s presence, the constriction inside him relaxed to a greater degree; the guardrails he’d so carefully set around his daily life wobbled. He found himself again drifting into reveries, as he hadn’t done since he was a boy.

It wasn’t anything untoward that drew him to Alice Liddell. She had an ineffable quality, an intriguing coupling of wisdom and innocence in her look and manner. Oddly, Dodgson felt as if he might learn from her—he didn’t know what exactly, only that whatever it was might dissipate the mysterious pall he felt over everything he did.

One afternoon, he took the Liddell girls out for boating trip to Godstow. They stopped to rest, and while Edith and Lorina played in the shallows of the River Isis, as that particular stretch of the Thames was called, Dodgson lounged on the grass with Alice.

“Don’t you want to join your sisters?” he asked.

“No,” she replied.

Dodgson thought this a charming answer. “But why not?”

“After you’ve been a princess and had your queendom taken from you, as I have, it’s hard to get excited about a mess of fish and weeds in a river.”

Dodgson laughed. “Whatever are you talking about?”

Alice explained that her real name was Alyss Heart. She spelled it out: “A-l-y-s-s.”

Her mother was Queen Genevieve of Wonderland, she said. She and the queen and a party of courtiers had been celebrating her birthday in Heart Palace when her nasty aunt Redd, a grimacing woman with flaming red hair, attacked. It was a horrible, bloody scene, with Redd’s raging card soldiers fighting Queen Genevieve’s chessmen.

“Card soldiers?” Dodgson interrupted. “Chessmen?”

Alyss tried to describe the platoons of fifty-two soldiers who would lie in a stack before being dealt into action, then unfolded and fanned out to fight. She did her best to present him with a picture of the pawns and rooks and bishops under General Doppelgänger’s command, but what she really wanted to tell Dodgson was that she didn’t know what had happened to her mother, though she assumed the worst.

“You don’t know?” Dodgson gently pressed.

No, Alice explained, because Redd’s most fearsome henchthing, The Cat, had tried to kill her and she’d had to jump into The Pool of Tears with royal bodyguard Hatter Madigan, a graduate of the Millinery, where Wonderland’s elite security personnel trained. She had lost Hatter in the pool but was sure he would find her eventually and take her back to Wonderland.

Alice went on to tell Dodgson everything she still remembered about Wonderland: the giant mushrooms, caterpillar-oracles, tarty tarts, and looking glass travel via something called The Crystal Continuum.

“Let me see if I understand you correctly,” he said. “People can travel through looking glasses, enter through one and exit from another?”

“Yes. I’ve tried it here but none of the glasses work.”

“Tell me more about this Red Queen of yours,” Dodgson encouraged, thinking of Queen Victoria, her excesses and intimidations.

He took out pencil and paper, taking notes and sketching, as Alice went on at length about Redd—and about The Cat, and Hatter, whose top hat flattened into a weapon of spinning

blades. She described how General Doppelgänger could split into the twin figures of General Doppel and General Gänger, and each of them could then split into twins as many times as they wanted. She talked of her tutor Bibwit Harte, an albino two meters tall, with bluish-green veins pulsing visibly beneath his skin and ears a bit large for his head—ears so sensitive that he could hear someone whispering from three streets away. And, her voice dipping low in a sadness different in character from when she talked of her mother, she told Dodgson about her best friend, Dodge Anders, son of Sir Justice Anders whom the Cat had killed in front of her eyes at her birthday party.

Dodge. Dodgson.

He was the boy. The reverend was flattered, though he believed Alice’s stories to be the result of hardships endured before the Liddells had adopted her. It was likely, he supposed, that whatever had befallen Alice’s birth parents and landed her at the Charing Cross Foundling Hospital had been quite traumatic, and that she invented stories to cope with the horrors of her life. Mere stories? No, an elaborate fantasy life—harsh, to be sure, but startlingly inventive.

“You have the most amazing imagination, Alice,” he told her.

“I did,” she huffed. “It hasn’t been so powerful since I’ve been here.”

Charles Dodgson, energized and inspired to a pitch he’d never been before, didn’t realize it then, but with his pen he was going to try and bring some relief to this delightful child, this product of unknown traumas. He would transform her gruesome, violent imaginings into the ridiculous, rendering them laughable rather than things to be feared. And if, by turning Hatter Madigan into the Mad Hatter, General Doppelgänger into Tweedledee and Tweedledum, and Redd’s assassin—who could morph from an ordinary kitten into a murderous humanoid with feline head and claws—into the grinning Cheshire Cat; if while Dodgson did all of this, he also managed to satirize the current state of British politics and its major actors, well, all the better.

Dodgson—let’s call him by his nom de plume, Lewis Carroll— had written poems and little satirical works before, even published a few of them in journals he deemed not very special. (It’s curious to note that he’d first used the pen name Lewis Carroll the year he met Alice Liddell, for a poem he published in 1856.) Still, not Carroll’s earlier publications, not mathematical puzzles, not the beauty of logic, had fired up his imagination as much as transforming what he deemed to be Alice’s make-believe into a playful adventure novel.

He saw Alice regularly over the next several years, during which he found himself aglow with creativity. The world looked somehow brighter, more vibrant, and for the first time he thought himself to be truly happy. He had already taken up the new art form of photography (again, curiously, in the same year that he met the Liddells), but now his explorations of that medium increased until he was something of a master. He created an invention for taking notes in the dark, as well as an early iteration of a game that we know today as Scrabble. In mathematics, he developed new ideas in linear algebra. And when not exercising his imagination in these various ways, Carroll found time to befriend gifted artists and scholars—John Ruskin, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and numerous others.

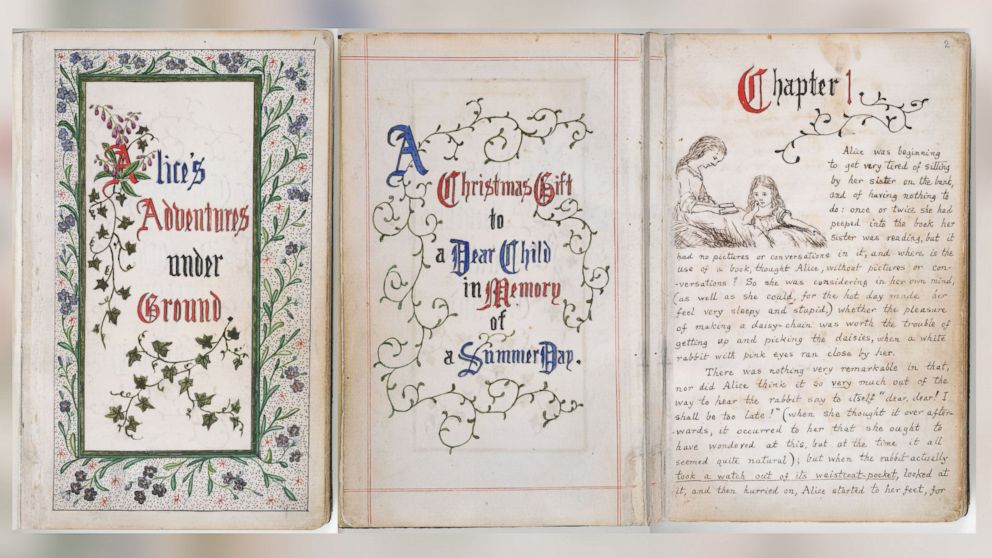

With the manuscript of what he had titled Alice’s Adventures Underground at last finished, he presented it to Alice Liddell one afternoon on the banks of the River Cherwell. It was wrapped in brown paper and tied with a black ribbon. Dodgson watched anxiously as Alice untied the ribbon and carefully removed the wrapping.

“Oh!” the girl exclaimed, her mouth flat-lining in displeasure.

What sort of title was Alice’s Adventures Underground? She wanted to know. And why was her name misspelled when she had correctly spelled it out for him? And who was Lewis Carroll?

“I thought it would be more festive than saying it was by me, a stodgy old reverend,” Carroll said.

Festive? She had told him little that was festive. Alice opened the manuscript. Its dedication took the form of a poem, in which her name was again misspelled. Her gaze caught on one of the stanzas:

"The dream-child moving through a land

Of wonders, wild and new,

In friendly chat with bird or beast –

And half believed it true."

“Dream-child?” she murmured with growing concern. “Half believed?”

She turned to the first chapter. Carroll noted at once the quiver of her bottom lip, how she slumped as if she’d had the wind knocked out of her.

“I admit that I took a few liberties with your story,” he said. “Do you recognize the tutor fellow you once described to me? He’s the white rabbit character. I got the idea for him upon discovering that the letters of the tutor’s name could be made to spell ‘white rabbit.’ Here, let me show you.”

Carroll took a pencil and small notebook from the inside pocket of his coat, but Alice didn’t want to look.

“You mean you did this on purpose?” she asked. He had purposely twisted her memories—which, with his help, she had hoped to prove to everyone were true—into this foolish, nonsensical book?

“I . . . I thought it . . . m-m-might help you,” Carroll stammered.

Alice jumped to her feet, yelling. “No one is ever going to believe me now! You’ve ruined everything! You’re the cruelest man I’ve ever met, Mr. Dodgson, and if you had believed a single word I told you, you’d know how very cruel that is! I never want to see you! Never, never, never!”

She ran, leaving Carroll at the riverbank. Shaken, unsure of what had just happened, he picked up the manuscript, still warm from Alice’s touch, fearing that this was as close to her as he’d ever be again.

The publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland met a lukewarm reception at first, but within six years, it became a phenomenal commercial success. “Lewis Carroll” was famous, and the book’s royalties gave Dodgson the financial security to do whatever he wished. Although pleased by the public’s reception of his work, he preferred to remain at Oxford, teaching, serving tea to close friends. In short, he preferred to live modestly as a retiring bachelor.

Some of this might have had to do with depression. Alice was making good on her word never to see him again, and all friendly association with the Liddell family had ceased on June 27th, 1863. Without the enlivening spark of Alice’s presence, the pall Dodgson had known before meeting her resettled over his life. His interest in photography deserted him. He invented nothing.

He had heard through gossip that Alice resented what fame had come to her as the purported inspiration for Adventures. How it must have galled her, he supposed, that in betraying her memories with his book (as she believed), he had thrust a fame on her founded on absurd falsehoods. He gave up hope of ever spending time with her again and uncharacteristically destroyed four entire volumes of his diaries and ripped pages out of others— pages that detailed afternoons with Alice Liddell, as well as the day he broke with the whole Liddell family.

Life trudged on. Dodgson pursued his mathematical interests and wrote poetry, but the efforts felt mechanical. By 1870, after the death of his father had darkened his overall mood even further, he recognized that he needed Alice, his “dream-child” (he thought the designation a compliment), to help him—not just to live as fully in his imaginings as he’d once been able to, but also for the strength she somehow gave him to contend with a world full of grotesqueries, corruption, and petty vanities.

Dodgson never would have believed that Alice Liddell was one day going to return to him: a young woman with enlightened notions, on the cusp of marriage, who would not only forgive him for his so-called betrayal but recognize that, because of the fame his book had brought her, she had an opportunity to effect substantive societal change that wouldn’t otherwise have been available to her.

Nor would Dodgson have believed that, unexpectedly buoyed by Alice’s company, he’d again find himself writing as Lewis Carroll. Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice found There, a sequel to Adventures, was published in 1871. A nonsense poem entitled The Hunting of the Snark entered the marketplace in 1876.

All of these things came to pass, reminding Dodgson that, in his best days, he had always preferred to believe in the impossible. Happily for him, another impossible thing happened: as Miss Alice Liddell recruited Charles Lutwidge Dodgson into her schemes for bettering the lives of the unfortunate, he discovered a world that even Lewis Carroll couldn’t have imagined.