As an amateur scholar and die-hard enthusiast of everything to do with Alice in Wonderland, I have launched a podcast that takes on Alice’s everlasting influence on pop culture. As an author who draws on Lewis Carroll’s iconic masterpiece for my Looking Glass Wars universe, I’m well acquainted with the process of dipping into Wonderland for inspiration. The journey has brought me into contact with a fantastic community of artists and creators from all walks of life—and this podcast will be the platform where we come together to answer the fascinating question: “What is it about Alice?”

It is my great pleasure to have Christopher Monfette join me as my guest! Read on to explore our conversation, and check out the whole series on your favorite podcasting platform to listen to the full interview.

FB:

Chris Monfette, I’m happy to have you on the show. The title is All Things Alice, except it's really turned into a podcast about pop culture and creativity.

You're deep into Star Trek: Picard. I'm curious where you left off with the show, given the strike, and what your state of mind is. Are you on the picket lines?

CM:

We were lucky in terms of Picard because Patrick Stewart had only wanted to do three seasons. They knew going into it, because I didn't come in until the second season, that it would be three and out. So there was a really unique structure to Picard where it was handed off from showrunner to showrunner for three seasons in a row. The novelist Michael Chabon had developed the first season with Akiva Goldsman and was the vision and the showrunner.

In Season 2, they had brought in Terry Matalas, who was my showrunner for 12 Monkeys, and Terry brought me. Because of the crazy pandemic pandemonium, rather than Terry taking the reins completely, season two was split between him and Akiva. Terry didn't really get the keys to the car until season three, which is really the season that we feel we were allowed to do the kind of Star Trek we signed up to do, and really tell the story that we were longing to tell. And I think we did it really well. I’m very proud of what we did and what our team accomplished and I think folks have received it really well. It’s been really embraced critically; the fans seem to have loved it. I feel like we checked all the boxes and took the right path with that season.

What’s interesting is it started to air concurrently with all of the strike talk. It was very strange. In one half of your brain, you have all this anxiety about, “Oh my God, am I not going to work? How long is this going to go? How am I gonna pay my bills?” Then, the other half, it's constant praise from the internet being like, “We love this. This is great week after week. This episode is better than the last episode!” There’s this weird feeling of getting all of these rewards that you hope for as a writer at the worst possible time. You can't put them to use. There's no show to springboard to right now. I can't leverage this into selling my own thing or going to work for some show I dreamed of working for.

FB:

That’s very entrepreneurial of you to think, I need to leverage success. That's a big thing in Hollywood, but at the same time, given there's the WGA strike, there are a lot of folks that don't have that reinforcement of their work every day. That must be a nice little buffer against the reality of a strike. Are people jonesing for a season four? Is that a possibility?

CM:

Just to be clear, it's not so much leveraging, it's wanting to continue doing the thing that we love doing, telling stories.

Coming off of season three, there's been real fan fervor. Terry, in the press, pitched his vision of how Picard could go forward, sans Patrick Stewart, and move into a series that he called in his head, Star Trek: Legacy.

The fans picked up on it and really started demanding it. There's a petition, a lot of online momentum, to make that show a reality. We've never been in a position where we're more poised to springboard into something like that and to convince Paramount and CBS that it should be the next Star Trek adventure. Yet, we just can't. All the writers are hungry to get back in the room and tell more stories in this universe with these characters. But everything's on pause right now.

FB:

There’s all that uncertainty of when the strike is going to be resolved but then, it’s the worry of, have you lost that momentum from the fans to use their enthusiasm to hopefully convince Paramount to move forward. Fingers crossed it’ll work out.

CM:

I think we can get there. I'm hopeful. And if not, this will resolve itself. There will be other shows and entertainment is not going away. But, the strike is a fight worth fighting.

The strike is very interesting because there are several tiers of writers. Some writers are new to the industry and just got their WGA cards. Some writers are pre-WGA. Some writers have worked, for quite a while, but are not paying their bills off of WGA credits or are staffed on shows. Then you have the middle tier of writers who go from show to show and are also developing. They don't have other jobs. I'm one of them. This is how we pay our bills. Then you have a whole upper tier of writers, the Ryan Murphy’s, the J.J. Abrams’, the super producers, and even just the very hyper-successful showrunners who have overall deals or have had incredibly successful shows. They can financially weather a six-month or eight-month strike in a way that other writers can’t. It’s rare when you can get all three of those tiers, who have varying degrees of urgency, to agree that this is a fight we have to win, and we have to stick it out no matter how much it pains us to do that. And I think we're doing it.

FB:

It seems the middle is holding, which is going to be important. One of the issues is staffing and what the writers room looks like. From 12 Monkeys to 9-1-1 to Picard. How would you describe each one of those shows in terms of how many writers were on staff versus the arguments surrounding the strike about making sure that there are staff writers that are learning their craft and moving the show forward?

CM:

I'm of several minds about it. I've been fortunate enough to work on shows, whether it was 12 Monkeys, 9-1-1, or Picard where we had eight to 12 writers in the room at any given time. We were really blessed to have full rooms certain seasons, but we never had an empty room. All the shows that I've worked on really benefited from all of those voices creatively. I've always said this in interviews, Terry Matalas, especially in 12 Monkeys, and Picard really has a talent for conducting the orchestra. He knows how to staff a room of writers, each with unique strengths, and then knows how to get them to play off of each other so that there'll be certain writers who are better at the comedy, there'll be certain writers who are really good with the big sci-fi 35,000 foot ideas. Other writers are dialogue people, and we'll all write and rewrite each other's script and it'll be better for everybody’s contributions. Whereas something like 9-1-1, for example, you're assigned an episode, you write the episode, the showrunner polishes it, then production tells you what's too expensive, and what's not expensive. It's less of a symphonic collaboration of voices because it's a little bit more episodic with the case-of-the-week structure. So that was a really unique experience as well.

But in all of those experiences, you had the benefit of 8, 10,12 different minds sitting around a table pitching ideas that all complemented each other and ultimately made the work stronger or made the episodes more interesting.

Now, I do totally support the idea of individual auteur writers/directors who have a story to tell they feel can only be told in their unique voice. You look at Aaron Sorkin, you look at Noah Hawley, creators who have very unique and specific voices and visions. I feel there needs to be room in the conversation for singular auteur creators to be able to create, but I do think that to protect the vast majority of shows that really do benefit from the collaboration of voices, there should be a minimum room number so that ultimately the producers can't reduce what we do to a UK model, where scripts are freelance and you can't ultimately pay your bills.

If Taylor Sheridan has to put up with a room of three writers sitting around, he's free not to use them, he's free to write every script, he's free to use them for research or to pop in now and then and ask for an idea. Otherwise, let's just subsidize them showing up to work and eating snacks, and leaving at night. But I do think there does need to be a minimum room size to support what we're doing in the long term. The amount of shows that have those singular visions are so few and far between compared to the vast majority of the rest of the industry that this is a hill worth dying on.

FB:

But also, isn't it the idea of these mini rooms that you've been putting together, where they're not officially assured it's moving forward, and yet you're doing the same work that you would have been doing if it was greenlit? That seems to be a major problem.

CM:

Yeah, we need to get more clarity and definition on what constitutes a room, the length of the room, and the population of that room. I think mini rooms started as a potentially interesting idea. Before we greenlight this thing and bring in 10 people, the showrunner wants to bring in two or three of their closest collaborators and really figure out what the thing is before we dive into it. The principle is unique and interesting. But the problem with that model is, all of a sudden, it was, “Okay, well, if you think you can get most of it done with three people in 10 weeks, why are we going to give 10 people and 20 weeks? So the burden falls on too few writers, who then aren't allowed to go to set, and aren't allowed to amass that experience and learn how to produce.

I certainly ascribe to the theory that so much of what we're talking about stems from a lack of smart, creative producing in Hollywood today. When streaming became a thing 10-15 years ago, when it was a kernel of an idea, the thought was always, let's take the mid-budget movie ($50-$90 million) and amortize that budget across 10 episodes versus two hours. We'll be able to dig into the character and we’ll tell more story, I don't think it was, necessarily, this level of spending a billion dollars on The Lord of the Rings IP was the initial thought. When you're making these big spends that equate to what you spend on a theatrical mega-budget summer blockbuster, you can't possibly recoup your costs. We’re at a point where shows are spending so much money that they don't have to spend.

I look back at my time on 12 Monkeys, where I went and lived in Toronto for 18 months, and produced seasons three and four, back-to-back with Terry Matalas and a handful of other writers. That is a unique and rare experience. We produced a time-travel show where the protagonist was going to different times every week and it often looped back on each other. There'd be something in this episode that didn't pay off for 10 episodes. We crashed a time-traveling city into another time-traveling city. We had spectacle and production value and we did it for $2.7 million an episode. We were really smart about how we produced it because we understood when to go abroad, how to cross-board episodes, how to work with actors, and work with each department to get the most bang for your buck. That is not something we would have been able to do if we didn't have writers who were emboldened and taught and instructed and had the experience of learning how to keep those costs down so that we didn't have to do it for $5-10 million an episode when we could do it effectively for less than three.

I think we have to empower power writers to learn their trade and to become good at that aspect of this industry. The more you can keep budgets down, the more that we can keep studios from having to freak out about their bottom lines and having to take content off platforms. The more we can keep writers working, the more shows we can produce for the same amount.

FB:

The notion of streaming coming in was that they were going to buy their way into the market. In the same way, Amazon sold books and lost money, but took a big piece of that business, when Netflix came along and spent a lot of money on House of Cards, they bought their way to the top echelon of Hollywood and continued to spend, and everybody jumped on. Now, of course, the market’s been saturated.

What's going to be desirable, I would think from a studio standpoint, is finding folks like you and that team that did 12 Monkeys and trying to produce shows for more reasonable costs with broader storytelling and hiring more writers and empowering them.

CM:

I also think there's an interesting thing going on from an audience perspective, too. You're seeing it with the box office reception to The Flash or even Indiana Jones, for example. Spectacle is so available on every platform. You can go see a billion-dollar, Lord of the Rings fight sequence on TV. Also, the stakes in big-budget, blockbuster IP-driven stories are the end of the world, the destruction of the universe, and the collapse of the multiverse. There’s no respite from these artificial ridiculously high stakes that you can never top.

It’s never been more important for writers to get in there and say, “Look, you don't have to do a $250 million Avengers movie, where the fate of the world hangs in the balance again. Maybe you can do three $100 million Avengers movies, where the stakes are more emotional and more personal, but the concept is still really high.” What's Ocean's 11 with the Avengers? You can find all of these touchstones to make movies that still have all this stuff in them that audiences love, but are more creative about the story, the emotions, and the themes. You can make them cost less too and then the audience will feel like they haven't seen this in the eight other things.

The one Marvel show I responded to the most, and this isn't a criticism of any of the shows on their own, but I really liked She-Hulk. Because the stakes weren't like, “Oh my God, this is the end of the world!” It was, is she going to find happiness? Is she going to find contentment? How is she going to navigate this strange, unique thing that has happened? And how could she do that and keep herself and her family and her friends together? It was written cleverly and warmly and it probably didn't cost $300 million to make. I found it really refreshing and really original. You need writers more than ever to tell you how to take all the great ingredients that IP gives you and execute them at a high concept level at high quality for less money.

It's not superhero, or I.P., or blockbuster fatigue, but there’s a certain level of stakes fatigue like we're telling the same story over and over again.

FB:

People are looking for a fresh take. I remember when The Joker came out and it was so dark and so interesting. I did not expect that it would be so successful.

But the great thing about television is, there are so many options. I saw on Twitter, you mentioned Drops of God. I've been watching Drops of God along with Hijack on Apple and that's a really unique, interesting story framed in a way that I never would have expected a story about wine and vineyards to be framed.

CM:

I loved it. It's so beautiful and unique. It's the perfect way to lean into this thing that streamers are looking for now, which is, wanting to make one thing that can serve a bunch of audiences. It figured out a way to tell a French story and a Japanese story in an American way that allowed any of those audiences to plug into it and yet it was emotional and visually interesting. It’s one of my favorite shows this year by a mile because good writers figured out how to execute it well.

FB:

It’s a great example of writers having a voice that AI could never replicate. Also, that idea of the multicultural. They have the same thing going on in Hijack, which is pretty exciting.

CM:

That show speaks to what we’ve been talking about. We’re gonna build one set, we're gonna spend our money on that. Then we're going to tell a seven-episode story. That’s a fairly financially responsible way to make television and if you can execute that at its highest level, I don't think audiences will find themselves wishing for $100 million on screen. I think they'll be captivated by what they're watching.

FB:

Your story and your career trajectory are interesting. You started as a journalist. Was IGN your first gig?

CM:

I began my career in PR and marketing. I was always a nerd growing up and my first real gig in that universe was working for Microsoft and launching the Xbox 360.

FB:

You said you were a nerd. Were you taking your interests and saying, “How am I going to figure out how to work at a cool company that does games?” For those people that are coming out of college and thinking about being in the business, you need a first step. What was your strategy?

CM:

Growing up, I always knew that I loved reading, writing, and video games. I loved books. I was a big genre nerd my whole life. I was going to Fordham University in New York, which doesn't have a phenomenally strong film program but they do have a good communications program and decent screenwriting classes. But that was never going to tip the scales for me so I started writing for the school paper. I didn’t have any money but I still wanted to play video games and listen to music and read comics and I realized I could call companies and ask to review products they'll send to me for free. So, I really embraced this idea of journalism as a way to get paid to consume and do all the things I love doing anyway and write, as well.

The second strategy that I figured out was that I was going to get more value from internships than from the actual classes. So I started interning for a lot of the same people I was asking for stuff from. I was an intern for Fox’s marketing and PR department. Then I went to Sony and then DreamWorks and I tried to learn as much about the industry as I could and make as many contacts as I could. So, when I got out of college, I was equipped to go do marketing and PR. It wasn’t necessarily my dream, I wanted to be a writer, but it was adjacent to the things that I cared about. After a couple of years, eventually, the journalists I was working with every day said, “Hey, you can make more money over with us playing the video games and watching the movies and critiquing them than you can shilling for them on a PR site.”

I've always said to anybody who asked me because there is no one path to success in this business, that the most you can do is put yourself where lightning can strike and cover yourself in as much tinfoil as you can. That's really what I was doing in the early years of my career. I went from college to that one job which led to another job that was a little bit closer to what I really wanted to do. Then, while I was at IGN, I was able to make all these great friendships and relationships with producers and actors, which five years later paid off with my first staffing gig. There wasn't a grand master plan, it was a selfish desire to get paid to be the thing that I had been my whole life, which was just a genre nerd.

FB:

How were those internships?

CM:

They were all basic internships, all unpaid. The college only asked you to do one, but I did three, just to learn and grow and make those relationships and I liked doing them.

My first job as an intern was going to the entertainment section of hundreds of newspapers and seeing if there was an article about something our company had done, physically cutting it out, putting it on a piece of paper, and photocopying it. Then I’d put a book together and make 100 copies of that book and distribute that to everyone. That wasn't a particularly rewarding job but I became very close with my boss and over three of those internships, I came out with a pretty complex understanding of how the business works.

FB:

You also wrote a novel while you were working at IGN, as I remember.

CM:

It was a short story. When I was at IGN, I got to meet Clive Barker, who had always been a hero of mine as a kid. I was doing an interview with Clive and we were talking about my upbringing and my love of his work and he goes, “I don't think you're a journalist. I think you're a writer. Pick something of mine and adapt it. I'll give you the rights.”

He mentored me and I did two movies for his production company. I never made a ton of money, but they were great opportunities to get my start and take my writing to the next level. Through him, I got to do a Hellraiser graphic novel that was eight issues long and this Nightbreed story. It was one of the centerpiece stories at the heart of this collection they were doing. A bunch of great authors were contributing short stories and novellas to a collection based on his Nightbreed universe. That was a joy. He was the first major personality with a reputation in the industry to take me under his wing and see my potential and try to nurture it.

FB:

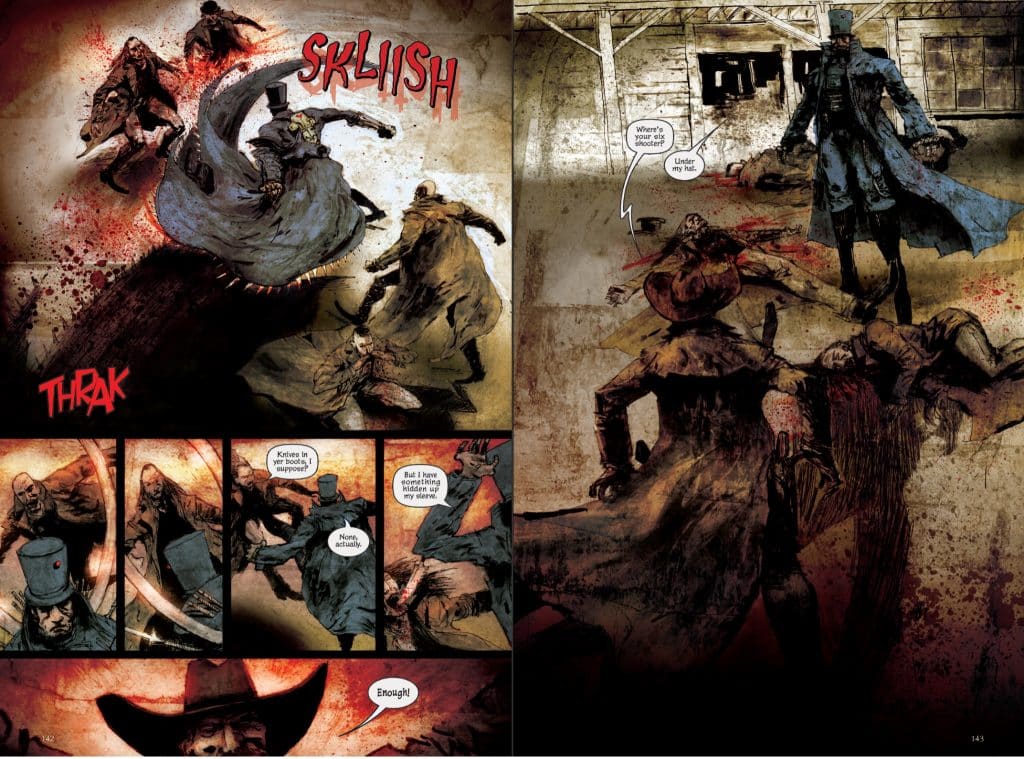

I remember you wrote an episode of Hatter Madigan for me around the same time. You had pitched me the story of Hatter in the Wild West in Death Valley.

But you come across as the kind of person that has a lot of story engine inside of them. How do you see yourself as a writer in terms of your strengths?

CM:

My story is unique in the sense that I grew up loving video games, comic books, and all the nerd stuff that a lot of really terrific genre writers grew up with, but my uncle was a theater guy. He introduced me to writers like Sam Shepard, David Mamet, and Arthur Miller. So, I became a fan of really finely honed, character-driven dialogue. I was also fortunate enough to be a teenager in the Miramax years, the rise of the independent movie, where there were all these amazing writers like Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh, with hyper-specific voices were being allowed to make these really interesting films.

Then you had someone like, I know that circumstances have made the name a little passe at this point, Joss Whedon came along and took all this really sharp, stylized, amazing dialogue and applied it to genre storytelling. These people can be talking as cleverly as someone in a David Mamet play or an Aaron Sorkin drama.

I like to think that’s where I bring value to a room. I can do the big swing 35,000-foot sci-fi concepts but then also more granularly, do a great scene with really crackly dialogue and sharp character work. I'll never write a broad comedy. I'm not funny. We had a writer on Picard, Cindy, who’s tremendously funny. I could never do that and I'm in awe of that kind of talent. But dialogue writers were really my biggest influence in film and TV coming up.

FB:

I studied acting for a short time under Stella Adler and one of the things she required was for you to study playwrights like David Mamet and understand where they were coming from so you could really grasp the work. I think I learned more from playwrights and the economy of storytelling and the necessity for great dialogue to make things work. It’s satisfying as an actor, but I was really fascinated with their backstories, the reason they became writers, and how these plays came about. That was very influential to me in writing The Looking Glass Wars.

CM:

No one will ever accuse me of writing a scene with naturalistic dialogue. There’s no right or wrong here but I know a lot of writers who want their characters to talk the way people really speak. I'm 180 degrees in the opposite direction. I love words and I want my characters to use those words as best as they possibly can and in the most inventive combinations. I look at shows like Succession, and I'm just in awe of the way they'll take a simple idea and wrap it in the bacon of this incredible verbiage. Or Steven Moffat on Doctor Who, who has this amazing crackerjack, very twee kind of dialogue, or Amy Sherman Palladino has this machine gun rat-a-tat-tat of words. I really love the mechanics of constructing a sentence with wordplay and rhythms in a way that other writers don't find value in because, for them, it's about making the scene as human as possible and as relatable as possible. For me, if I go to the theater and I see a truck turn into a robot, I want the dialogue equivalent of that. I want to go see entertainment in a way that I don't experience in real life. I want to see people talk at a level I wish I could talk at. That’s my jumble of influences.

FB:

With the story you wrote for me, the first thing that I read was Hatter’s interior dialogue. That's how the story opens. I thought you were able to get into his head and be very poetic at the same time, and then set the story up for a classic villain who underestimated our exceedingly talented and deadly hero who is “the other”.

The dialogue was very poetic and not all that realistic. I think there was a line where the bad guy said, “You have a six-shooter?” because he wanted to draw on Hatter and Hatter responds, “Yeah, it's under my hat.”

CM:

I remember when you first introduced me to your world, Hatter was the character that I plugged into immediately because I am such a Doctor Who fan and I'm so deeply influenced by it. Hatter Madigan and Doctor Who are nothing alike but they are these lone heroes unstuck in time and they have the flexibility to find themselves moving through their narratives in these nonlinear ways. There's something I've just always liked about those kinds of stories, whether it's Sam Beckett and Quantum Leap, or Doctor Who. These characters want, in a weird way, what everybody experiences. They just want to go from Point A to Point B to get the thing that they so desperately want, but because of the way their life is structured, they can't get there that way. There’s something beautiful and lonely and interesting, whether the character is as serious and action-focused as Hatter or as whimsical as Doctor Who. I've always loved those kinds of stories.

FB:

I was quite rigid in the story structure with Hatter, not in terms of dialogue, but in terms of following historical events, so that it would feel like the audience could really suspend disbelief in terms of the notion that this was a real place. But in exploring television, and exploring the idea of doing this as an ongoing show, conversations I've had with you and other people was, “Why doesn't Hatter go through a portal to our world in 1871, why shouldn't you have him time jump and start to create that fish out of water in all sorts of times, and have that contemporary lens?” It’s a really interesting idea, getting into The Looking Glass Wars through Hatter and his time in our world. I just haven't quite been brave enough to pull the trigger on that, because I keep thinking, “Where's Alyss in this? Would I be cutting back to Alyss? Or would I just simply leave her until this series runs its course for three, four seasons, and then introduce Alyss and expand it?

CM:

You’ve quite purposefully created a world that there are 10 ways into. You could choose any of those and they would be wildly successful approaches.

FB:

I don't know if they'd be wildly successful but maybe if you helped me out, they would be. But I'm exploring that. You and I worked together when we did that mini room to explore the structure of The Looking Glass Wars TV show. The Queen's Gambit hadn't come out and I thought it would be interesting to start the show where you have a cold open of the adult character and then you would use the first episode to tell the origin story. But I still think that most people who read The Looking Glass Wars hook into Hatter. He's the most popular character.

CM:

Hatter, in some ways, is the wish fulfillment. We all wish we could be as cool as that character and as composed and as strong and stalwart. I always loved Alice in the original books because she's so driven by a sense of curiosity and discovery. I think we all are. We all in our own lives come to a rabbit hole and wonder what's down there. And it's, are we brave enough to jump or not? Curiosity, especially for writers, is the best quality you can have. The most important quality you can have is to wonder why and to wonder what and then to go chase those things and experience them and manifest those things in your own life. I think what you've done in your fiction is to expand upon that. You have these two central characters and one is about curiosity and discovery and then the other is very much about loyalty. He is on this mission, experiencing this other world, but it’s with an almost singular purpose to get back to where he's from. He's not interested in shedding that purpose to discover and consume and learn. He just wants to blaze through the world. I think there's a little bit of all of those characters in everybody.

FB:

Though, the wish fulfillment and blazing ahead, in terms of doing a series, would probably get a bit old if he wasn't able to have interior difficult problems, that he's failing, and how that affects his search and his personality and these obstacles that he comes across.

You brought up the word curious. In my book series, I always use imagination. What do you think about the combination of curiosity versus imagination to ultimately create something?

CM:

I think imagination is just an extension of curiosity. Curiosity is standing in front of the rabbit hole and imagination is picturing what might be down there and the reality is, whatever you'll discover when you jump.

I have traveled more than this but, maybe you've never been to Europe before and you're curious about it, and you want to break out of your American view of the world. So you get your passport and you go to Europe, and you taste the Netherlands and you see Paris and you see Italy and you experience all these wonderful cultures and foods. Imagination is taking that experience and saying, “Okay, what if that happened in a fantasy world? What if that happened in a sci-fi world? And you're able to write those stories better because you've empathetically, as a human being, shared that same degree of experience in your own set of contexts and life.” The key is coupling that sense of real empathy for what is out there in the world and then applying imagination to it. Curiosity and imagination are inseparable.

FB:

There are levels. It’s also research and curiosity, immersing yourself in whatever that thing is that you're interested in, and then trying to imagine what you're going to create and then working on creating that. It's all a part of this zone that we'd like to get into where those two come together and give you some inspiration.

CM:

I think some writers can do both and some writers have made wonderful careers out of doing one. Certain writers have their things. Carl Hiaasen will always write books about Florida. He knows one thing and he's gonna drill down until he's explored every nook and crevice of the one thing that he knows well. Other writers will say, “Well, I want to experience the world and I’ll go write that.” Both are fine because they're driven by a curiosity to understand either many new things or better understand the one thing that you find yourself around. It takes the same quantity of imagination to tell the smallest, most granular story as it does to tell the biggest, most fanciful.

FB:

Were you introduced to Alice in Wonderland through the novel, the Disney movie, or something else?

CM:

Through the books. Growing up, my grandfather always really encouraged me to read. He would go to yard sales and tag sales and people would just throw books out on their tables for a quarter. So my grandfather would always come back from the sales with a paper bag of books that he found for me. A lot of those books were older. Doc Savage novels, which still predated me by 20-30 years. So, at a pretty young age, I was reading John Carter of Mars, old Doc Savage books, and pulp stories that he would pull from these tag sales. Eventually, he brought home a really beautiful hardcover version of Alice in Wonderland. I can't remember exactly what age I was but I remember it being really formative for me. I really enjoyed it and then I think the animated versions came after that.

My experience with Alice was unique in the sense that my first visual of it was whatever I made up in my head. I wasn't cobbling it together from cultural reference points.

FB:

Which most of us are doing now because it's so deeply seated in culture. Have you seen it much in television? I see images of Alice popping up. I think it came up in Stranger Things.

CM:

It's gotten to a point now where you're like, “Yeah, okay, we get it.” It’s a staple but if I hear “White Rabbit” as the soundtrack to a given scene ever again it’s, “I get it, guys.” Alice is a universal story in the sense that every story, whether it's Star Trek or Lord of the Rings, it's the hero's journey. We're leaving home, we're going to a strange place where we're going to find out things about ourselves and that change in us will allow us to complete our journey and hopefully come home. That structure of storytelling shares inherent DNA with Alice so it makes sense that it pops up everywhere.

FB:

Do you have a favorite? Whether it's a song or a movie or any piece of art of Alice that resonated with you along the way?

CM:

The American McGee Alice games because I like horror a lot. It was great to see someone step in and do a darker, horror-driven take on these things. I like that game quite a bit and there's been talk ever since it came out about there potentially being another so it gets refreshed in my gaming zeitgeist every couple of years. I remember that making an impression upon me in terms of one of the first adaptations of that material that was really interesting and cool and visual and unique and spun it in a way that it wasn't just telling the same story. It was telling a different story from a different point of view, which I liked a lot.

But I'm of the opinion that the best adaptation of Alice in Wonderland has yet to be made. I go back through all the various ones that I've seen, and I don't think I love any of them. The Disney ones, whether it's the Johnny Depp one or the original, they’re so polished. I'm waiting for Guillermo del Toro to try it or Tarsem Singh, or a filmmaker who weirdly uses practical and CG in an interesting way because so much of Alice to me is tangible. Other parts of it are very painted and illustrative. None of the other adaptations I've seen get the balance that I've pictured in my head for so long.

FB:

It’s also a struggle, because she's 13, and it's seemingly episodic. Everybody that's done a take on it, including myself, tries to find a structure that allows the reluctant hero story to play out in a way in which you can suspend disbelief and buy into it.

CM:

Stranger Things is an Alice in Wonderland story in a weird way. We went into the upside down, and they cast those kids young and they made it work.

FB:

But in television, you have a little bit more opportunity, and certainly, when you have a show, and even movies that have both young characters and adult characters, you have those four quadrants. That show can be nostalgic as an adult and it can feel completely fresh for my 13-year-old.

CM:

There’s a weird Ouroboros effect with these IPs. With Alice, the book is published and it comes into the zeitgeist, and it inspires all these other works. There is an Alice in Wonderland quality to all of these other different stories that are being told in different genres. It gets absorbed into the zeitgeist in other ways, whether it's a poster in the background or a music cue that nods to their roots in Alice. Then, eventually, it comes back around to, now we want to remake the thing that inspired all the things that inspired us to remake it. Do we remake it using all of the iconography of the things that it inspired? Do we use the visual language of all of the different iterations? Or do we have to find some new visual language to tell that story again? Because otherwise, it’s a song that's singing itself.

That’s what you've done so well with creating your world. You found another way into it, that visualizes it differently and contextualizes it differently. It feels like Alice without feeling either too dissimilar or too similar. I think that's what you guys have been doing brilliantly in your world.

FB:

Thank you. I've been trying to push outside of what people know as Wonderland. Whether it's bringing Wonderland to another culture, another timeline, or expanding the geography of Wonder nations. I'm looking to expand with other writers and other voices who can see the world in a way that, having done this for 20 years, I might not be able to do or see. It’s been interesting and exciting to talk to other creators about handing over the universe and saying, "What would you do with this?”

That whole collaborative effort, whether it was working with you in the room, collaborating on a graphic novel, and now working on a game, it’s very exciting to have a world that is big enough with a bright enough canvas that attracts other creators.

CM:

Even looking at something as recent as Across the Spider-Verse. Even just that little section where they dip into Mumbatton. For 10 minutes of the movie, we're going to show you what Spider-Man through an East Indian lens looks like. There's a lot to explore there and you realize, even just telling the same story with a slightly different aesthetic, or cultural view, gives it all these new layers. It's not just a quick glow-up. It gives it a real depth. I could have spent two hours in just Mumbatton alone learning what that kind of Spider-Man story would be like. It's great that you give other authors voices to explore these things from other angles because there's a lot to find there.

FB:

I know you have a lot of original work. You're obviously on this big show but you've written a lot of pilots. I know before the strike, you were pitching projects. Tell me where you're at with some of your original work. I remember you did something called The Survivors.

CM:

I had a run there where I would write these pilots that I would send to my reps, and they would go, “Yeah, no, I don't think anyone wants to do anything with that.” Then, a year later, some other version of it would be huge. I had written a script called Survivors, back in 2014, which was about a support group for the survivors of various horror movie scenarios. At the time, I was patting myself on the back for having such an original idea. But my reps were like, “Oh, this is a little meta. I don't know if it's gonna work, blah, blah, blah.” Years later, how many seasons deep are we into American Horror Story? Also, there's a terrific novel called Final Girl Support Group that came out a few years later that touched upon the same concept.

Still to this day, the pilot that I'm proudest of is a restaurant drama. It’s about two brothers who couldn't be more different, forced to come back together after the death of their father. But, at the time, my reps were like, "Nobody wants a food show.” Now you have The Bear.

All you can do is write what you're passionate about writing and keep writing, which is the problem I'm struggling with now. The strike is such a stressful time that it tempts you to take a break. You think, “I'll put my pen down because I can't do anything with what I make anyway, or blah blah blah.” But that muscle can atrophy. So, you have to pick up the pen and work at it every day.

I've got a horror feature I'm working on now, which I can't say too much about. But every day I go to write it and I kind of shake my head and think, “Why am I this insane?” This idea is crazy. Hopefully, there'll be some life in that at some point. Terry Matalas and I have a number of things on deck that we'd like to do, and hopefully, we'll be able to do once the skies clear and the strike is over. We have a retelling of Phantom of the Opera that we've been wanting to do forever and we'd love to find a way to make that happen. Terry certainly wants to keep on exploring the world of Star Trek and hopefully, the powers that be will let us do that. It’s writing a new pilot, writing a new feature, and then hoping when this all resolves itself, we can get back in a room because that's really where I love to be. I love sitting in a room with smart people coming up with cool stuff.

FB:

In the room we put together you always were the first to jump in almost every time.

CM :

It’s ‘cause I’m obnoxious.

FB:

Yes, you are very obnoxious, which is such a superpower. I wish I was a lot more obnoxious having witnessed you jumping in but you were a driver of the room. It was super helpful to be fearless in sharing an idea that people could jump on and start to riff off of so you need that. It’s no surprise that you've gone from show to show and that you and Terry have a strong partnership and understanding.

CM:

I’m starting to believe this, and maybe I'm wrong, but I feel like it has a lot to do with having worked on a time travel show. Because when you're working in time travel, not only do you have to have these big creative sci-fi ideas and couple that with emotional character-driven ideas but you have to think, “Well, if we do this, then it undoes this because it goes back in time so that wouldn't work." Your brain teaches itself to iterate really quickly, to have a really good idea, explore it, realize if it contradicts something else in the time travel, and if it does, throw it out and go back because you can't lose the time. Then if it works, great, go to the next idea.

I found that a lot of the writers who came from 12 Monkeys have all described entering subsequent rooms and feeling like they're going faster than everybody. They’ll pitch 10 things and maybe other people in the room have pitched one and they feel like the asshole, like, “Oh my God, I am bullying my way into the room? Am I being too loud? Am I pitching too much?” And I think it's just because we've taught our brains to iterate and calculate the math of a story beat in multiple timelines, and it makes your brain faster. It really is a testament to the more you do this, and the more you do it with great people who challenge you, the better you become. You can take half of your idea and half of their idea and make something that's better than either idea. It's an amazing feeling. There's nothing I love more than working with great writers.

FB:

I have had a delightful time chatting with you, reconnecting, and talking about the business and your career, and fingers crossed for the strike and fingers crossed for this new idea.

CM:

Thank you for having me. I always love reconnecting with you and it's great to be able to have a long-form conversation and really dig into it. This was a blast.

For the latest updates & news about All Things Alice, please read our blog and subscribe to our podcast!