As an amateur scholar and die-hard enthusiast of everything to do with Alice in Wonderland, I have launched a Podcast that takes on Alice’s everlasting influence on pop culture. As an author that draws on Lewis Carroll’s iconic masterpiece for my Looking Glass Wars universe, I’m well acquainted with the process of dipping into Wonderland for inspiration. The journey has brought me into contact with a fantastic community of artists and creators from all walks of life—and this podcast will be the platform where we come together to answer the fascinating question: “What is it about Alice?”

It is my great pleasure to have Nick Madonna and Lee Thomas join me as my guests! Read on to explore part 1 of our conversation, and check out the series on your favorite podcasting platform to listen to the full interview.

FB:

You have that beautiful mic.

LT:

Yeah, this was a gift from Riot when I was working on Convergence, and it was right during COVID. So, we had to do our initial temp V.O. all from home. It was the first time they did that, and, as it happened, it worked magically. My wife was also working in the office next door, so I was sat in my front room with my laptop, this mic, and a duvet and pillows around me and I was doing the temp V.O. for one of the characters. So, she's in one room, closing a deal with the producer and she has to explain to all of her colleagues that her husband is an insane Creative Director on video games that does voices.

FB:

I did not know you did voices. That’s awesome.

LT:

Yeah, I'm a theater kid. From school, I always wanted to act. I auditioned for the National Youth Theatre and I was into musical theater. No one wants to direct theater at school because no one really understands what a theater director does. They all want to be an actor. But, I was like, “Oh, I'll paint the sets. I'll do the directing. I'll do whatever.” The love of my own voice comes from that, I think.

FB:

I started the same way, by the way. Well, I started off as a skier and I was hired to do the stunts in these two movies, Hot Dog: The Movie and Better Off Dead. I got to know the director and he said, “Oh, I think you can be a day player.” I had one line in a movie called Amazon: Women on the Moon. It was a sequel to Kentucky Fried Movie. I had never done any acting before and the director said, “Oh, I really like what you did. I'm gonna give you a little bit bigger part opposite Carrie Fisher.” Suddenly, I had a two-day part where I was her husband, and she gives me a venereal disease and I go blind and I have to walk into a wall. I have to do this pratfall. So, I did this thing and I got two or three jobs in a row and then I said out loud to somebody, “This is really easy. I think I'm going to do this.” From that day on I never got another job.

LT:

That's always how it works.

NM:

Making your debut, and Kentucky Fried Movie, that's one way to go--

FB:

One way to go to the bottom. But, nevertheless, this is my first podcast talking about video games and talking with creators and designers and producers of video games, and folks that I’m collaborating with, as well. To start off, I’m really curious about your first introduction to video games? What got you excited to be in this business and to design games?

LT:

I was kind of lucky when I was a kid. My dad worked adjacent to programming so when I was very, very small, we had Apricots and black and green old school monitors in the house. So, I always remember playing whatever games my dad liked. Golf was the first one. I couldn't hit a ball in real life, but I could get a hole-in-one with a computer game. That was a that was a fun kind of like, “Oh, okay, I can be pretty good.” That was really fun. Then, we got one of the, they were called Video Packs, I think in the US, but in the UK, they had another name. The licensing between the US and Europe, it was still at that point where a console was released in America and a console was released in the UK and the names were completely different. We had a sort of a Pac-Man clone and a Space Invaders clone and a Submarine clone game. So that was my first introduction to video games and I love them to bits. But I think the first time I played something where I was like, “Oh, this is interesting. I want to do something with this.” It was probably Wolfenstein and Doom, those first 3D, first-person point of view games. You would play those levels again, and again, and again. Because, of course, you already have the shareware version, because my dad bought the PC he wasn't going to buy me the games. So, I had the free shareware version and I'd just play that again and again and again.

Then a friend of mine had the same thing and I called him up modem-to-modem, and then we were playing multiplayer. From that point on, I loved games a lot. So yeah, they've always been there.

FB:

It's interesting that you bring up your dad because I was really close with my dad. Anything my dad was interested in, I ended up gravitating towards. I imagine there's an emotional connection to that time with your dad and playing those games. I had a similar situation with golfing. I was a big Tiger Woods fan so I started playing his game and then I optioned the artwork for the 18 Infamous Golf Holes and I thought I would try my hand. It never got across the finish line but I really relate to the Father-Son aspect of finding things that you have a love for and that you can share.

How about you, Nick? What was your first intro into the game space?

NM:

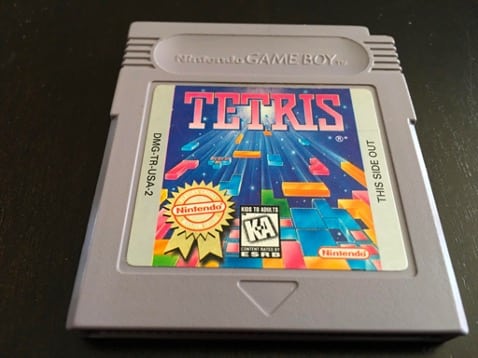

Similar to Lee, but also some differences. We had a Texas Instruments computer very early on in the mid 1980s. It didn’t do a lot, but it rendered some images on screen of animals that I could press a button and they reacted to that. That was really my first, true introduction to games. But my main difference with Lee’s story was that my real first game system, and what really got me into games, was a Gameboy. My dad, through his work, made some trades over the holidays, and was able to get his hands on the original Gameboy, the big gray brick version, which was hard to get when it came out. He was able to get me a Gameboy and a copy of Tetris. That was my first gaming system. That was my first real sense of, “This is mine. It's more than a toy. There's something there.” I could just sit by myself and play it in the corner, and no one would bother me. That’s what got me started down the path of being really interested in that kind of stuff.

That Father-Son bond, I had that too, but it wasn't around games. It was a long time before I actually had my first console but what I bonded with my dad over was comic books, pulp novels, and things like Conan and Sherlock Holmes. We went to the comic store every week and we were collecting and reading. There were certain things that eventually dovetailed into the games, especially the fantasy and the mystery elements. For example, the latest game we worked on was a Justice League game, so there's a lot of love there. It has gone from games and media around games and that's influenced a lot of what I'm interested in now and what I like to work on.

FB:

What I really love about doing this podcast is, everybody who’s creative is pretty much touching pop culture and we've already been talking about comic books and games. Lee, we're talking about acting earlier, you're talking about your first love being movies, and synthesizing those things to come up with your own creative vision.

Lee, could you give me a little background and connect the dots from that experience with your dad and creating those games, to what you're doing now with Rich Liebowitz at your studio?

LT:

To follow on the theme, it all goes back to my dad. This is always the case. My dad played lots of sports and when I was born, he reserved a season ticket for me at Aston Villa, which was our local team. Safe to say, I'm not a big football fan. My younger brother ended up being the sporty kid and I was much more the art and theater kid.

The other thing I had with my dad, because it wasn't going to be sports, was movies. Every Saturday, my dad would take me to the video store. The key one was Superman, which I think I must have watched thousands and thousands of times. My nan literally said, “I'm not going to come and babysit for Lee if he makes me watch Superman again.” I used to know all the words. But then when we would go back to the video shop, I would search for other Christopher Reeve movies. One time I picked a very old film he did that was really unsuitable for kids. We started watching it and my dad was like, “Oh, no, no, not this one.”

Weirdly, that period of searching through the video store was one of the first times I was ever introduced to Alice as well. It was the 1972, the Peter Sellers version with Fiona Fullerton as a young Alice. I got to that because I really loved James Bond and A View to a Kill came out in 1985. Fiona Fullerton is a Bond girl in it. She plays the Russian spy in a Japanese bathtub with Bond, and she goes, “Oh, Tchaikovsky.” My favorite. As a kid I'm just looking at the musical references and I don't understand the double entendre that's going on underneath it so she's always the Tchaikovsky Bond girl. So, scanning through the video store, I see Fiona Fullerton and my dad’s like, “I know her. Where do I know her from?” I'm like, “You know her because she's a Bond girl, Dad. Obviously, you pay attention to Bond girls.” We picked that video up and I was not prepared for the surreal, very bizarre, 1970s version of Alice in Wonderland. I had obviously come across the book in some way, but this was the first time seeing it. I think I saw it before I saw the Disney film as well.

It's very, very odd. I went back and looked at it a few days ago just to sort of refresh my memories and I was suddenly like, “Oh, now I know why I like Monty Python. Now I know why I like Mighty Boosh. Now I know why I like surreal comedy because the movie is like a sketch that goes into another sketch, which goes into another sketch, which goes into another sketch. It really doesn't conform to traditional narrative. It’s more like a video game narrative. In games, you're always trying to get the player to divine where to go next themselves. That's the ultimate. If you can play a game without the game stopping you and saying, “Oh, hey, go and see this quest,” or “Hey, go over there,” Getting that player to feel that sense of agency is the goal. The 1972 Alice in Wonderland film reminded me of that. She has options and she has to just keep going.

FB:

The novel is so episodic, and I thought they tried to make that work for them in that movie. By the way, I forgot that Michael Crawford was the White Rabbit and he went on to play Phantom for all those years. Dudley Moore was in it too.

LT:

There’s quite a few people that pop in it as well. Especially for me, everyone in that cast was in British Kids TV, which is really weird in a fantastic way for those who haven’t experienced it.

FB:

That's a really great story because with Alice, not only were you intrigued, but it's the way the story was told and the humor triggered an interest in that kind of storytelling.

Same thing with you, Nick. You have your PHL Collective company. You're the CEO. Or how do you label yourself, or is it just as the guru of games?

NM:

Yeah, I don't even know. I founded the company. CEO. Head. I just do whatever needs to be done to make it work.

FB:

When you're an owner of some sort you wear a lot of hats. But connect the dots for me from your 80s computer to your high-tech operation you have going now.

NM:

It actually started more low-tech. That love of comic books and my weekly habit of going to the store with my dad was what got me started in art. I was okay in school. I played a lot of sports. But art was the thing that I really excelled at. That's what I could really focus on and it's what I wanted to do. For a long time, I was drawing comic books, and I was taking drawing classes and kind of figuring things out. Eventually, at the end of high school, after completing independent art study I applied to an art school here in Philadelphia called the Tyler School of Art, which is an extension of Temple University.

At that time I was like, “I want to do art. This is what I want to pursue. I would love to be an artist for Marvel or DC. This is my thing.” I talked to a recruiter and talked to some teachers, and I showed them just this massive stack of sketchbooks I had of character studies and characters and panels and pages. I was, no joke, literally laughed out of the room. They didn’t consider comic books to be a true form of art. According to them, that was not a pathway to being an artist. Oh, my God, I still remember it and I hold that grudge to this day. And I should, rightfully so.

But taking that information, taking that low point I was looking at, in the early 2000s, I thought to myself “Okay, if comic books are no path forward, what can I do with my art? How can I utilize those skills to pursue something that I'm really interested in?” Games were always important to me and I continued to play throughout my youth and through high school. Just about that time, there started to be some programs around Game Design and 3D Art and understanding how to manipulate the computer to output things that could be rendered on a television or printed on a PlayStation disc. That started me down that pathway of trying to figure out how I pivot, utilize these art skills, but do something which maybe has a little bit more of a path forward. So, I pursued 3D Art and I have my degree in 3D Art and Animation. From there, I utilized those skills to work my way up through games through being an artist, a 2D and a 3D artist, a Quality Assurance tester, being in production, being in business development, and finally running a studio. I made a third pivot from 2D art and comic books to 3D Art and Animation to the boring business guy that sits on his computer all day. But I do more than that. I’ve rolled with what has worked really well for me and what has been fulfilling and that's where I am now with my studio and what we're doing.

FB:

I really love that story. Because, when you're dealing in art, and that's your passion and that's your path forward, it's pretty scary. You don't get that much support from school. You’re lucky if you get any support from your parents because that doesn't spell success, or being able to take care of yourself.

I also love the pointed obstacle, and that there's a visceral reaction still in your body. I really have that as well, from the many rejections of my novel. Some of the very pointed rejections, which were not really about the book, but about my background My dad used to always say, “Rejection is a great thing, son,” and I go, “What are you talking about?” “Because the door might get slammed on you, but it's going to open another door up a bit, and it'll probably be the door that you should have opened in the beginning.”

NM:

I did get that support at home. Luckily, my parents saw what I could do, and they encouraged me. There was, to this day, still a lot of fear of going into a field that they don't understand. Just a lot of parents kind of have that, especially with new media and a lot of what we do. But seeing that success and seeing the growth within that field, and seeing that their support has made their child successful is important.

Because, those moments of rejection are defining. They’re lessons and they're also growth moments for you as a person to figure out, “Well, am I just going to give up on the thing that I really love? Or am I going to find a way to make this work? Am I going to find a way to move forward?” I think those are really important lessons. As we've done talks at schools, because a lot of kids today are fans of games, and they want to go into game design. I always think back to that moment, I made sure not to crush a dream early. But be realistic and say, “Look, these are the things you need to study. If you are really interested in this, I would suggest doing X, Y, and Z.” I don't tell them it's impossible. I don't tell them, they’re terrible or anything like that. I make it positive and give them the right kind of pointers so they can go on a similar path, or maybe even an easier path than what I took to where I am now.

LT:

I also never realized that you were from an art background, Nick. Me and Nick met, not that long ago. But as soon as we met, there was something where I just got on with this guy. I had the same thing, I wanted to draw, but it was never quite good enough. I went to art college, and it was like, “What's this stuff like that? That's not important.” I ended up going to art school because I wanted to go to film school and I rang up the National Film School and said, “I’m 15. How do I get there?”

If anyone's listening, and they're thinking about what to do next and they don't quite know - go and do a foundation course, or go and do a year where you try lots of different mediums. The first year of art school, you try painting, you try sculpture, you try technical design, or costume design. It’s about bringing different perspectives to view. I think the more, this is how I ended up where I am, the more you can be like Alice, the more you can be curious, the better. I'm just way too curious about everything. Why is that? When’s that happening? Why is that happening? Eventually, your parents stopped being able to answer you and point you in the direction of books or teachers and that carries on growing and growing and growing.

I think that's one of the best things about the game industry versus the film industry. In the game industry, by and large, most people are very, very curious about everything. I think in the film industry, people have much more of a sense of, “Hey, I'm keeping to my lane. This is what I specialize in.” The notion of heads of department is a very rigid hierarchy. That hierarchy exists in video games as well, but it's more often connected to salary banding, rather than actual responsibility on a project. The reality of video games is you've got the player in the middle of it, and the player is completely unknown. They're this random entity. You'll have to think about which way the player is going to turn the game, not necessarily where you want to turn the game. That conflict of who the author is, is the main difference between film and games. I'm really enjoying the game side of it at the moment. That's not to say, there's not a lot to do on the film side, because that's fun as well. But in gaming, that unknown entity is really fun.

FB:

The film business is difficult on the business side of it because it's more rigid. They take big swings. I know they do the same thing in the game space but there really is a collaborative effort, it seems to me, to make games fully realized compared to how it works in movies, where if you give the power to the director, and the director knows what they're doing, they drive the ship. But in games, there are so many parts that you need to collaborate with.

So could you talk about how you guys met and how you collaborate? Then I want to get into the game Justice League that you just released, Nick, because it's pretty exciting.

LT:

The game business runs much the same way the film business runs in terms of relationships. Nick and I met because of Rich Liebowitz, who runs Epitome, who I'm working for now. Rich, he's one of those, what Malcolm Gladwell would call a serial networker. He knows so many people. He has a very good profile and an understanding of what drives those people and what they want. When you meet so many people, you can be like, “If I put these two together and get them to have a conversation, I wonder what's gonna happen there?” That’s what Rich did with me and Nick. He put together a couple of meetings. I got to see Nick work. Nick got to see me work. There was a mutual attraction. A mutual admiration of each other.

You have to have humor in whatever you do. You have to. If I'm working with someone who has no humor, it's just over. As soon as you can find that with someone, you can understand that person and that they are pushing towards the same sort of quality you are, it might not be exactly what you like, it might not be to your tastes, but if you can see them working, you can see that productivity and it's very, very easy to find good collaborators in the game industry, for sure.

There's a ton of neurodiversity in games as well. Again, it is very, very different from film. When I worked in film, I learned about communicating ideas. I learned about leadership. I worked for some great directors, and I got to see those directors be in control, in a sense. But if you really analyze what that control is, they're really just marshaling other great leaders. A great art director, a great director of photography, a great writer, and then a director above. And that director works differently with each of those, those three people. The art director, you go off and you talk about this, and maybe you'll go to a museum and you'll look at photographs, and then a costume designer, maybe you'll go to a show. There’s different ways of drawing lines or creating tighter relationships so you can enable that person to push and go further. That's inherent in video games as well, but even more so.

FB:

Nick, Lee sounds like he really knows what he's talking about. Can you tell me about the actual mechanics of the two of you working and a little bit of the history?

NM:

Our origin story is definitely connected through Rich. As Lee mentioned, he works for Rich’s company, Epitome, and Rich has been in the game industry for a long time. We've been working together for the past couple of years and Rich is helping me with strategy and business and augmenting the efforts that I've been doing over the past 10 years to grow the business. There's a lot of things that we want to do and a lot of games that we want to make and having someone like Rich has been invaluable to how we plan for the future.

I met Lee through Rich. He connected us and as Lee said, there's just a lot of similarities between us in terms of comedy movies and games. There are a lot of touchstones and that’s going to be key to any good friendship or any collaboration. We got on pretty quickly and we’re collaborating on one project, which is an original IP from my studio called Silverlake, which is a horror title that we're really interested in making. A lot of the early ideas for the game and the comic were bounced off of Lee and he’s given a lot of valuable feedback. It helps strengthen our friendship, but also, I trust his feedback. He's worked on a lot of really great things and I value his input. That's the origin story.

FB:

I saw the demo for that horror game, and it has a really interesting and dark tone that’s so different from your latest game, Justice League. I don't think people, if they saw both, would connect that this is the same creative force. To Lee's point, sometimes people get outside of the box or they're in a box and they want to get outside of the box, or sometimes people just have creative ideas.

Tell us a little bit about that game and the premise. What other horror games would you compare it to?

NM:

One of the things that I think is really important for any creative is to be able to work on something that they have a connection to or feel a connection to. While we love the games that we make based on big IPs, internally at the studio, we're also really big fans of horror and survival, and a lot of movies and novels in that vein that really influence our thought process behind Silverlake. For us, again, we want to make something that we would want to play. That's always gonna be a driving force for a designer. When we're playing really great survival games that are out there, we're like, “This is really fun. But what if we did it this way? Or what if we added this extra layer on top of it? How do we make this different? How do we inject something new into this genre?” That’s where Silverlake came from.

The story takes place in the 1930s in the Pacific Northwest, and it's based on indigenous mythology and culture. We have a character who's come back from World War I and has seen and been through severe traumatic experiences. He comes home and is confronted with the expansion of industry in the Northwest, and how that has changed his family and his tribe's land. There are a lot of supernatural and horrific elements that are injected into that narrative, which we're playing on to really bring that horror element to it. Then, people might not be familiar with everything that happened in the 30s, what people went through, and what industry was like at that time, but thematically, there are a lot of common threads to things that are happening today. So we're pulling on those threads to make the story that we're telling, from all these years ago, relatable to players today. There are a lot of important themes and things that we're touching on, but essentially at the core of it, we're telling a horror story. We're telling a story about this man's journey, who he is as a person, and who he becomes after he goes through all these traumatic experiences. There’s a psychological and mental aspect to it. It's a really interesting property for us that we're working really hard on and very excited about.

FB:

I was in the film business, and still am to a certain degree. One of the reasons I started The Looking Glass Wars, is very similar to what you're talking about. Which is to have my own personal story that I could work on and develop and invite people into and have control over it. I always describe it as my sandbox, and I'm inviting these people to play in my sandbox and go crazy in the sandbox, but I know that it's my sandbox. But, we all have to make a living, and that's where the IP comes in. That's where I'll sell something or I'll get hired as a producer on something which isn’t mine. It's just a work-for-hire.

Tell me the difference about how it is to work on Justice League, which is obviously a big IP from Warner Bros. I imagine there were a number of issues in terms of restrictions or things you can and can't do. Can you share a little bit about that game now that it's public and being played around the world?

NM:

With any IP that you don't own, there's always going to be rules, there are things you can do and things you can't do. There are certain things that you need to be wary of, because there are other aspects of the brand, whether it's toys, or cartoons, or movies, that you can't step on. You don't want to overtake another product that the same company's doing. There are always those rules and we've dealt with those rules for a number of properties that we've worked on in the past.

What made Justice League different was the complete freedom that we had, which was awesome and unexpected. When I first originally pitched this game, I took a lot of my years of comic book love and poured it into this pitch and created a story that reintroduced players to the Justice League in a way that was different from how they were depicted in modern media. For the past 10 years, it's been the really cool Zack Snyder movies that are really dark. Everyone's super serious. That's great. Those did really well. That's how everyone knows these characters for the most part.

In our game, I really rolled it back to the origins of the Justice League, and the Saturday morning cartoons, and the things that make these characters so iconic and joyful. Why are they celebrated? Why have they lasted this long? When I pitched that to DC, they gave us the smallest amount of notes ever. That was really awesome because I was expecting massive rewrites to this whole thing that we did. They saw and identified that we knew what we were doing. We love these characters and we were showing that we love these characters through the game, through the gameplay, and through the choices that we've made. That alone, that confidence in us allowed us to really create our own little sandbox within the universe. We worked really closely with Warner Bros. and DC for two years to make sure that everything we were doing was spot on, we weren't stepping on other people's toes and that we were representing the characters in an authentic and accurate way that was joyful and fun and creative and new. Every step of the way, they were patting us on the back, encouraging us to move forward. It was really awesome.

I’ll tell you one of the really great things that helped us identify that we had something good. Sometimes it's hard to tell if the work is good, right? Internally, everyone likes it. You have collaborators or friends saying “Oh, this is really good. I really liked it.” But you don't know how honest that feedback is all the time.

We made big swings to get top-tier voiceover talent for the game. We had Nolan North, Diedrich Bader, Fred Tatasciore, we have these prolific voiceover actors doing voices in our game. When they started reading the script during the first V.O. session, they were laughing, genuinely, and that's when we knew. That's when we felt good. That was the one thing for us that made us think that the earlier feedback that we've been given is accurate. We can validate it now. Because, a lot of times V.O. actors get in the booth to do the job. It’s a work for hire, “I gotta read these five lines. S.A.G. says, "I need to be here for an hour, then I have to be out the door.” But to be in the sessions with these actors, and have their respect and have them laughing and have them saying, “Oh, wait, what if I make a joke right here? This line is great but let me do this little thing right here.” It was fantastic.

Every step of the way from conception to release, we've had all these really encouraging moments and, critically, we're seeing it in reviews. We're seeing players love it. We're seeing people understand that this is our love letter to the Justice League and to these DC characters. Getting that feedback now that people are playing it is really good and it's made the entire team really happy. Sometimes when you spend a long time on something, whether it's a movie or a game, you get lost and you're not sure and you feel some self-doubt before it comes out. You're like, “Oh if I see a bad review score, I feel like I've wasted two years of my life.” We've all been there at a certain point but when we started seeing the reviews come out for this game, we were over the moon. We're so happy that everyone understood it. We're really happy with the reception.

FB:

Congrats on that reception because it is a terrific game.

If you enjoyed this interview, be sure to read Part 2 of my chat with Nick and Lee!

For more information on Looking Glass Wars & Alice in Wonderland, check out the All Things Alice Blogs From Frank Beddor