As an amateur scholar and die-hard enthusiast of everything to do with Alice in Wonderland, I have launched a Podcast that takes on Alice’s everlasting influence on pop culture. As an author that draws on Lewis Carroll’s iconic masterpiece for my Looking Glass Wars universe, I’m well acquainted with the process of dipping into Wonderland for inspiration. The journey has brought me into contact with a fantastic community of artists and creators from all walks of life—and this podcast will be the platform where we come together to answer the fascinating question: “What is it about Alice?”

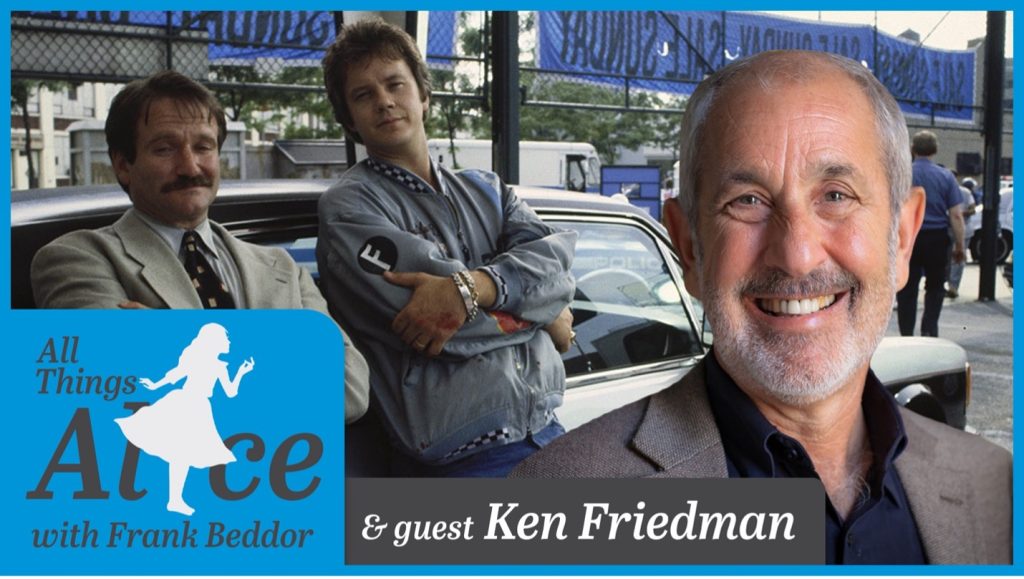

It is my great pleasure to have Ken Friedman join me as my guest! Read on to explore part one of our conversation, and check out the whole series on your favorite podcasting platform to listen to the full interview.

FB:

Welcome to the show, everybody. This is Part II with director and screenwriter Ken Friedman. I had such a good time chatting with him in Part I that I invited him back to talk more about moviemaking, all things Alice, and The Looking Glass Wars.

Hey, Ken, thanks for coming back for round two.

KF:

My pleasure.

FB:

So, let’s talk about movies and starting out. A lot of times people get their breaks because they make independent films, and the independent films have a voice, and they go to Sundance, they go to film festivals. Then they find themselves in Hollywood and they're trying to make the jump to more commercial ideas.

How do you advise your students in terms of the stories they choose, the subject matter, and the process?

KF:

Well, as a tenured professor of writing at NYU Tisch Graduate School of Film and Television, I get to work with really smart, really bright, and really interesting students. We want to help them find their voice and express their voice, not give them a template to the voice that's going to make their career happen. If they’re interested in money and celebrity, there are better places to be than Tisch Grad Film. They can go to Stern Business School across the square if that’s what they’re interested in.

Being successful and famous either happens or doesn't happen. If that's your goal, you'll have a better chance getting there making films that are totally personal. I think this business value new voices and new ideas. I think if you write to a commercial end, you don't have a chance to really establish yourself as an independent voice.

I talk about Chloe Zhao a lot because I worked with her early on, but she had a vision. And she made two low budget films for $60,000 each. Songs My Brothers Taught Me and The Rider, which is one of the best movies I’ve seen. Eventually she got her chances to make bigger films. But that was an outcome of her personal expression, not an outcome of her business design.

FB:

That means you believe what Mark Twain said, “Write what you know”?

KF:

I think that's become a bit of a cliche. And one I've probably used. Certainly, you can write what you know. But you can learn what you don't know. I did a television show called The Grid, which was about terrorism and counterterrorism, and we had characters who were terrorists.

Now, what do I know really know about what happens in the life of a human being who decides to be a terrorist and kill as many people as they can? I didn't know about it. I certainly wasn't sympathetic to it, my family having been on the wrong end of things at times. But it was a world I could find out about. We talked to ex-terrorists. We talked to politicians, lawyers, and clerics living in Arab countries and who have different points of view about Islam, politics, and culture. But what really helped me was reading novels written by young Algerians and young Tunisians about growing up in those countries. You could really hear their voice in those books and understand how things can go so badly wrong in somebody's life that they would choose that path.

FB:

Let’s talk about Cadillac Man. Tell me about working with Robin Williams. What did he bring to it? Did he improvise a lot of dialogue? Was he collaborative on set?

KF:

It was a great situation. Robin, early on, came to me and said, “The reason I'm doing this film is because I love the script.” But of course, who wouldn't want Robin to do his stuff? He’s funny. He's insightful. But he was smart enough to say, “I don't want to mess up the story. I don't want to change the story and change the character.” So we agreed we'd get one take as it was written in the script and then open it up to improv.

But, even more than that, we had table reads of the script in the weeks just before shooting. So if they improvised during the table read, I'd make a little note - This is a good idea. That was a bad idea. That night, I’d go back and update the pages. So I'd rewrite the dialogue as we rehearsed to reflect when they came up with good stuff.

FB:

It sounds like a great experience. I don't remember you having the same experience with Johnny Handsome.

KF:

Well, it was difficult until it happened. Chuck Roven had a book called The Three Worlds of Johnny Handsome and he liked the idea of the book but little else. It had the potential for a really good character. He was born with deformities and shunned by society so he gravitated towards the criminal world, where he became a master at coming up with bank robberies. So, the movie starts with him double crossed during a robbery and he’s thrown in jail, where the people who betrayed him have him killed so he won’t talk. Except he doesn’t die. In the hospital, he volunteers to join an experimental program where he’s physically transformed through surgery and cut loose. The question is, what’s gonna happen to him? Is he going to try and get revenge or is he going to focus on the woman he’s fallen in love with?

The first drafts of the script were really good. But then we went through three or four different directors and producers and the script was getting to the point where it was satisfying too many people. But Chuck finally took it to Walter Hill and he decided to go with one of my earlier drafts.

Working with Walter Hill was one of my great professional experiences. He knew everything about movie history and had worked with many of those people. He was a great guy and great to worked with.

FB:

And Mickey Rourke, how did that come about?

KF:

I had a very good relationship with Mickey. I don't know how he was brought onto the picture but he did a great job in the movie. Like a lot of movie stars, he didn’t like to speak a lot of dialogue, so we pared the dialogue down. Considering the history of the character, he would be very kept in and closed, not used to speaking, so I think Mickey’s desires to cut the dialogue helped.

FB:

Mickey was remarkable. He was one of those actors that had a stretch where he was so compelling to watch. Not since maybe Brando, was I so drawn to an actor.

KF:

We got Mickey at his height. It sounds strange, but he and I played racquetball several times a week during production. Never talked about the movie, though. Whatever internal stuff was going on, he used it in the character. He didn't use it in his life.

FB:

Who won in racquetball?

KF:

Generally, I did.

FB:

So when you adapt a book that's not very well known, you can really take the ideas or theme and go somewhere that might be different from what the intention of the book is. What's your take on when you're working on something that's well established?

KF:

There are times where I feel I want to work with the author, if they’re available, and I want to interpret their story cinematically. I don’t want to make it my story.

With Heart Like a Wheel, which is about drag racer Shirley Muldowney, I liked her and she was still active in her career so I felt like I had a responsibility to her. If the book is out and people are reading it and I like it, then I’d like to work with the author but also write it in a way that was readable. The readability of a novel is different than the readability of the script. But, I always went for the greater truth. Who was this person? What was at their core? Not, what happened on August 15? So for Heart Like a Wheel, we’re adapting real events in her life but interpreting them cinematically to try and get underneath Shirley Muldowney.

FB:

I found it really challenging to find a structure for The Looking Glass Wars when I was working on it as a movie property because of the age of the protagonist. Alyss starts at seven and then we see her at 13 and then she's a 20 year old. It takes place over 13 years and there's a lot of territory to cover in a two or two-and-a-half-hour movie. I was never really able to separate myself from the material in a way that would find the truth of the character until you and I started talking about it as a TV show. Because as a television show, that 13 year span and that life that Alyss had in Wonderland, then in our world, and then back in Wonderland, made a lot of sense over eight episodes.

Back when you were writing movies, they were such a driving force in pop culture. Now it seems to be in television, unless you're in the Marvel Universe or DC Universe. How much of your teaching at NYU has switched from writing for film to writing for television? And what's the difference in your approach with your students?

KF:

To begin, a good story’s a good story. I was responsible for developing the TV part of the program because I had just done television. The Grid was my next-to-last job before I went to NYU. At the time, I was really plugged into the TV world, and how to develop ideas into long form stories.

Now I'm back to teaching in a slightly different position of being head of thesis writing, and working with people on their long form stories. Sometimes TV becomes a feature or a feature becomes TV. It depends how many characters and what the story is. I think that the way people should develop their projects was different at the time that we talked about Alyss’ great potential, and it still has it, as a TV series. I look at the ways in which to tell the story differently now.

FB:

I was very excited after I saw the Queen's Gambit, especially the first episode. It used to be that you couldn't start with the young kid and stay with the young actress or actor because the audience would get behind that person. But it was seamless and Scott Frank did an amazing job.

KF:

The limited series is still the most intriguing television work to do as a writer because it has an end and it all fits together. I love series that are open ended but in terms of the writer expressing themself in this medium, the limited series is great.

FB:

In terms of deciding on a project, one of the things you said was, “What's the show?” What do you mean by that?

KF:

What's the experience you're meant to have? I think the document, whether it's a treatment or character descriptions, or verbal pitch, you're trying to describe what the series is going to deliver.

FB:

I remember you saying to me, you're selling the environment of Victorian England and Wonderland. You’re selling what happened. What happened to Alyss being exiled. Then you're selling the situation this girl find herself in and then you're developing the story arc of how she's going to navigate those worlds.

KF:

She came from Wonderland, escaped the coup, and was dropped into Victorian England. I still feel that’s a compelling character that I want to watch. I really want her to find herself and now that she’s found herself in the real world, can she go back and find herself in the fantasy world?

FB:

The imagination was also something you landed on. The theme is in the book and you always encouraged me to land on that in the TV show. That thematically it's about creativity and a creative person who's being denied in a repressive place, but they have all this potential. Thematically, it's “Who am I?” And this is her journey to find her way home. So it's also got a little Wizard of Oz to it.

Well, that was a fantastic conversation, Kenny. Thank you.

KF:

It was fun!

Check out Part One of Frank's interview with Ken Friedman!

For the latest updates & news about All Things Alice, read our blog or subscribe to our podcast!