This article now wears a banner at the top—“This article was published more than 17 years ago. Some information may no longer be current.” As much as it makes me marvel at the passing of time, the things that have indeed changed—it also draws my attention to how much is still “the same”.

The one thing I know is that: The Story of Alice in Wonderland will always endure, not by staying the same, but by growing along with us.

From pop culture to politics, she permeates our language and our creativity. Influencing and being remixed, sometimes sprinkled across the top so thinly you must look twice to notice a White Rabbit or Mad Hatter tucked into the milieu.

As a member in the ever-expanding army of Alice-aficionados, this sense of community has colored decades of my life. It’s amazing how many of the familiar names in this article I’ve bumped into over the years.

I watched my children play soccer, sitting on the sidelines with Gwen Stefani as she did the same for her own—all the while admiring her utilization of the Mad Tea Party in her music video. I couldn’t help but wonder, what would she use Alice to do next?

A similar sense of excitedly thinking “what next?” follows me as I comb my memories along with this article—American McGee is in the midst of developing a TV show for his Alice series of (gothic) games. Undoubtably it will be a daring take sure to turn heads, earning both excitement and ire— a phenomena I remember well.

Once I ended up debating Alice in pop culture on a BBC talk show with Sir Michael Morpurgo—who I discovered was not a fan of my book… but then again, he hadn’t read it yet! After checking it out himself, he liked it so much he gave me a quote for the jacket. (Check out the full interview transcript at the bottom of this page for more of Morpurgo’s take on LGW.)

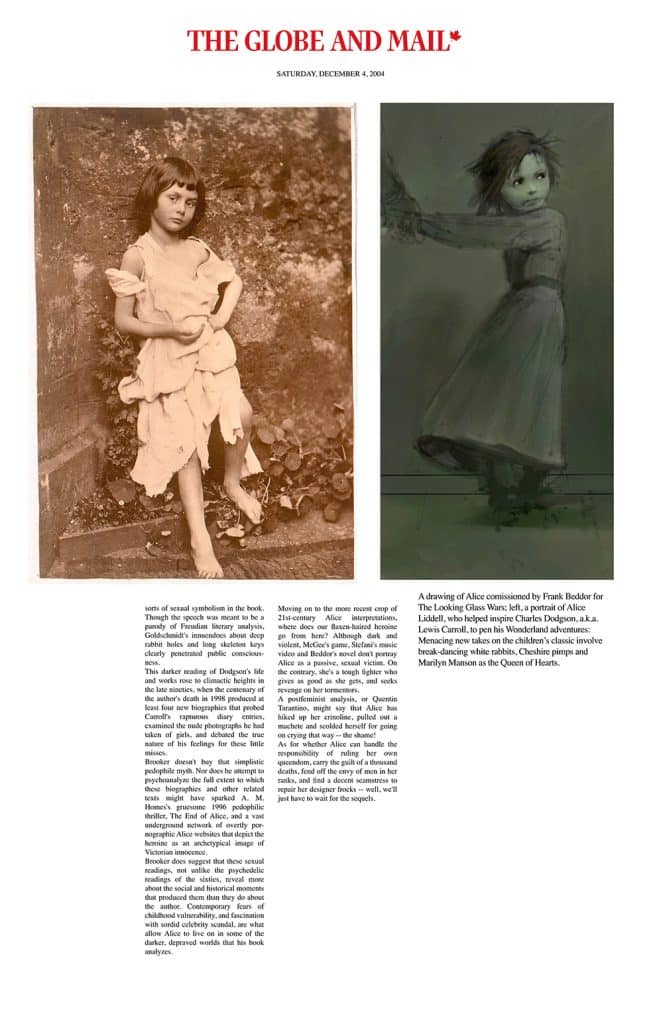

Though not everyone fell in love with my Alyss, I must admit. Will Brooker, the author of Alice’s Adventures: Lewis Carroll in Pop Culture never did come around to The Looking Glass Wars because he didn’t like my writing style. (This is exactly “Alice’s magic” of which we speak—there’s a version of her for everyone!)

This community is both insular and inclusive— we all work together, but the barrier to entry is almost nonexistent, because “everyone knows Alice”. Terry Gilliam, for example, was onboard to make The Looking Glass Wars movie with me in negotiations long since passed. While I’m never bitter about roads not taken (especially in Hollywood)—I will eternally be curious what that film would have looked like.

When Quentin Tarantino was rumored to be taking on a Star Trek project, I contemplated the value of stories and properties so large that they have room for decentralized iterations. What would Wonderland look like if created by the pulp stylings of the director that gave us Django and Inglorious Bastards? We can only wonder…

Reality has become stranger than fiction. I suspect the debate between what is Illusion and what is Truth will be the defining question of the decade. I rest content knowing the network of Alice fans will undoubtably endure and enrich this debate with their creativity—all thanks to the girl who fell down the rabbit hole.

For the original text of the article that inspired this trip down the rabbit hole of memories check out Alexandra Gill’s original post: Through Alice's looking glass darkly

Today Programme BBC Radio 4 with Michael Morpurgo

BBC: Michael Morpurgo what do you make of it [The Looking Glass Wars]?

MM: Well, I think you said it right. It's really brave, it's daring, but then it would be. I mean Frank Beddor is a man who likes taking risks. He skies down slopes at terrifying speeds. You know, why should he be scared of Alice? I mean I think the remarkable thing about the book it's very vibrant, it's imaginative, it's visual, it's very well researched. The question is, I guess, is whether you should tamper with something almost as holy as "Alice in Wonderland", and I don't know about that. I don't think any book is holy. I think we have a right to use - any writer has got a right to go to sources. I go to history, I go to legend, and this is just taking it one step further, but I do think he's been very brave.

BBC: Michael Morpurgo there's a very long tradition of writers returning to other people’s work isn't there?

MM: Yes, there is. Certainly. I've done it myself. The way I've done it is to adapt it. What Frank has done is to do a great deal more than to adapt it. He's interwoven the history, the new history, this newly found history of Alice and then told his own extraordinary, and believably visual and fast-moving tale.

BBC: Do you accept the new history?

MM: I don’t know really. It’s a jolly good story. I haven’t done the research so I don’t know. I’m afraid I’m a pretty old Father William and this for me is standing a story on its head, but it works. I don’t mind this at all. I don’t think we should be— we shouldn’t stand back and say you shouldn’t do stuff like this, because it seems to me a very interesting new way of looking at it. My problem is that I’m not a great fan of Alice in the first place. I’m a “Treasure Island” person. The world is divided into Treasure Island people and Alice people. I don’t want you to do it with “Treasure Island” please.

Woman’s Hour BBC Radio 4 with host Jenni Murray

interviewing Michael Bakewell author of “Lewis Carroll: A Biography”

BBC: Were the original Alice Books "girly", or what makes a book "girly" in the first place? Well, early this morning I spoke to Michael Bakewell the author of "Lewis Carroll: A Biography". He was in Culchester, Frank Beddor was in London.

BBC: Now Michael you read the books I think at eight or nine. Did you find all these cuddly animals and tea parties girly?

MB: No, not in the least. I don't think I'd read any girly books…The Alice books came something as a shock to me I think. I found them rather terrifying, because I got worried about all those transformations she has to go through, but "Through the Looking Glass" seemed to be an easier ride. I didn't realize then that in fact it's by far the more sinister book of the two.

BBC: How did you find Frank's version, Michael, with its fighting and its battles and its knives?

MB: I came to it rather cautiously I must admit. At first I couldn't see my way through it, then eventually I liked it a lot. I think it stands absolutely on its own two feet rather like Alice herself. I loved the world that was created. I love the use that was made of all the Wonderland and Looking Glass creatures, who I must admit, go through a total transformation in the book. I don't want to give away the ending, but in fact it emerges as a very moral story, which is really rather refreshing. Although, a lot of the atmosphere is like a terrifying child's video game.

BBC: So, Michael would it have been for a man like Lewis Carroll to choose a girl like Alice as the lead character, because she is quite boisterous, she does have adventure, she's not the Victorian ideal.

MB: She’s very far from being the Victorian ideal. I think that this is where I rather disagree with Frank. She’s pursuing her own process of self-discovery, and she learns to cope with all these dreadful things that are hurled at her. All these weird, and often quite frightening characters. And in both books, she emerges triumphant, you know putting everybody down, putting everybody down, putting everybody in their place, and as you say, she’s not in the least the little well-brought-up Victorian miss. She won’t stand any nonsense. She’s quite rude, and quite a lot of the text is frankly subversive considering t was written by a man in holy ordinance.

BBC: Michael just to go back briefly on what we were discussing earlier whether boys are alienated by having a female lead character. Is that still the case do you think, when we consider that novels like the trilogy Pullman "Dark Materials" has had a female lead in it. Are boys finding that more acceptable now?

MB: Yes, I think they are. I know quite a lot of boys who read the Pullman trilogy with enormous enjoyment, but also the honors are shared out of it, you know that it isn't only Lara all the way through, you do get Will as an alternative protagonist. This has been something that has occurred to me writing children's literature for years and years and years. After all “The Railway Children” kind of shares the honors out between girls and boys rather carefully.