As an amateur scholar and die-hard enthusiast of everything to do with Alice in Wonderland, I have launched a Podcast that takes on Alice’s everlasting influence on pop culture. As an author that draws on Lewis Carroll’s iconic masterpiece for my Looking Glass Wars universe, I’m well acquainted with the process of dipping into Wonderland for inspiration. The journey has brought me into contact with a fantastic community of artists and creators from all walks of life—and this podcast will be the platform where we come together to answer the fascinating question: “What is it about Alice?”

For this week’s conversation it is my pleasure to have Ed Decter join me. Read on to explore a sampling of our conversation and check out the series on your favorite podcasting platform to listen to the full interview.

FB:

It’s been a minute since you and I met at a Shakespeare class at UCLA and that is when you told me you were writing— I think it was your first script?

ED:

No, it wasn’t the first one, but it was a spec script that my writing partner at the time John and I decided to write to put out into the marketplace because that was an era where spec scripts sold very well.

FB:

Especially comedies, right?

ED:

Yes. And it all started with Shane Black with Lethal Weapon.

FB:

The movie we’re talking about is There’s Something About Mary. Just tell me, is that true, that you had read an article about somebody who had hired a private detective?

ED:

No, I had heard a story that a man who, just so happened he was gay, had completely lost touch with the person growing up that made him feel comfortable about being gay. This was sort of a more difficult pre-internet era where everybody wasn’t on Facebook, so he had hired a private investigator to find that person. Also, my writing partner lived at an apartment building that looked out to the bedrooms of these condos of a building or two over. There used to be a, this sounds especially creepy now in the me-too era, there was a woman who would get dressed but would never put down the blinds and we were young guys, un-married, and we would glance over there and we would wonder, “what if this private I was looking for her and would lie to the person who hired them and say, “no I didn’t find her” and then now that he has talked her and sort of stalked her he would know everything about her so he could talk to her very easy and we would have all this info. So that’s where the idea was born.

FB:

Well, it’s been 25 years, this summer will be the anniversary, and you bring up the me-too movement. I wonder, do you think, There’s Something About Mary that could be made today given some of the dialogue that Matt Dylan said in particular about working with retards.

ED:

There’s not a chance that it would be made today. There’s not a chance. But it's kind of great that it came together in that way because it found exactly the right director because those guys are really gregarious but they’re completely not mean spirited. Therefore they didn’t infuse it with any kind of creepiness.

FB:

Yeah, those guys are very funny, and they had a track record and they’re very charming and they convinced the studio at the end of the day.

ED:

Well, they didn’t convince the studio at the end of the day, meaning before they had shot they were supposed to have taken out everything in the script that we now recognize as funny. The dog going on fire, of course unharmed. The hair gel, the people singing in the trees, I mean they were supposed to take out all of that and they kept saying “yes, yes we’re taking it out” then they started shooting.

FB:

Right, and also, you’re talking about the prequel story when he was in high school with the braces on. That was 25 minutes of the movie and was critical to setting up his character and our sympathy for him. Especially when he got his junk caught in the zipper.

ED:

Yes. I said to Peter at the time, are you going to have Ben, who I think at the time is like 32, play his high school self? And Peter just said, “It’ll be hilarious.” And it was. He had the bad haircut and the braces, it was hilarious. If they didn’t have the street cred of having directed Dumb and Dumber, which made a ton of money, it never would have happened.

FB:

Well, I think that’s a really important point in all creations. When I wrote The Looking Glass Wars, I had an editor on me all the time. I mean I probably had to do 40 drafts and then I was really fighting for the cover art. I had all this great concept art. They were like "No. No, you don’t make a decision on the art." But at the end of the day, the art overwhelmed the choices they came up with, so they chose mine. The great thing about writing books is they really want you to have the voice and they really want you to take over but at the same time there’s all these publishing restraints that are not dissimilar to movie and TV restraints.

ED:

When you wrote the book I got extraordinarily jealous and decided I was going to write some books.

FB:

You’re so competitive.

ED:

I was so competitive, in golf too, and so I decided I was going to write books.

FB:

No, you said “if you can do it anybody can do it”.

ED:

No, no, no. I said, “If Frank is writing books, I’m writing books”. Now I had an advantage that you didn’t have at that time, I had written close to a billion dollars worth of movies at that point. So, she was the opposite, she would tell the copy editor “he uses capitals a lot because he’s a screenwriter and that’s the voice of the book, don’t change it”.

FB:

Wow—I never would have had that. So, how did you enjoy transitioning to directing?

ED:

It’s startling, when you grow up you think, “oh a director really makes all of the decisions and chooses everything” and it’s really not true unless you’re doing an independent movie that you have helped get the financing for. Then you have more of what Scorsese goes through with less budget.

FB:

Right.

ED:

When you work for a studio and you do a first-time movie, you get a lot of, "tomorrow there will be gene Simmons from Kiss in the movie." Then you will say, "well which part is he playing?" "He goes whatever part you write tonight for him."

FB:

Wow.

ED:

Yeah, that kind of thing.

FB:

That does not happen in independent films. On the movie Wicked, to your point. I was producing Wicked and then shortly thereafter Mary. In Wicked we had 2 million dollars, so the director was able to make all of the decisions in concert with what the whole production wanted. On Mary, once they left us alone, the Farrelly brothers shot everything they wanted because we were out of town.

ED:

A really good showrunner friend of mine said that “Movies are war. Television is government.”

FB:

That’s a great analogy.

ED:

Yeah, you can go off and make war and shoot something and literally burn down a town and then go home and have the insurance pay off the town and never go back there. But in television, you’re returning places, if your show is working and you go on for many years, your returning places for many many years.

FB:

Because you do both comedy and drama can we just take a step back to where the writing inspiration came from? To be able to write in these multiple genres whether it's drama or procedural or comedy. How did you find that voice?

ED:

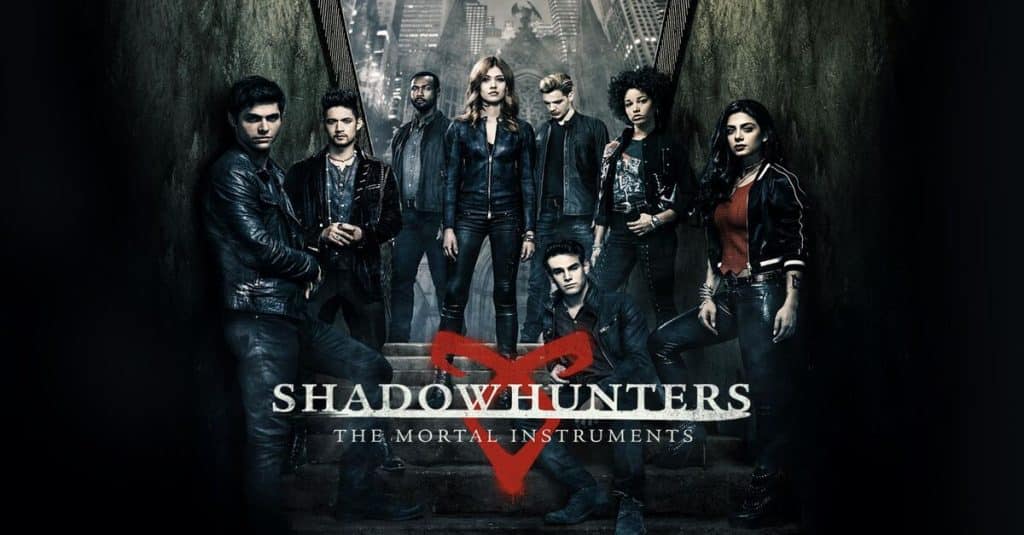

That’s a really good question and I teach this at the AFI. I always say you have to find the part of yourself that connects with a project and different parts of yourself connect with different projects. I created that show Shadow Hunters on freeform and obviously, it's very tough to connect with vampires or werewolves.

FB:

Again another genre, Fantasy.

ED:

Right and that connects to Alice very much and we will talk about that. That one I really could connect to, there was a mother who didn’t tell her daughter how special she was, much in the Harry Potter paradigm, and when she became 18 she started to come into powers that really confused her and then in fact jeopardized her because she didn’t know who she really was. It’s a classic paradigm in all of fantasy but I could relate to a parent protecting their kid so much that they actually hurt them in certain ways because they didn’t give them tools to survive on their own and that was essential to the first season of that show.

FB:

Do you think about it from the character and developing the character first? If you have a novel you have all the plot pieces so then it's about how is it going to work best for television. And if it's a series you’re thinking about the character arc for the whole series.

ED:

Right and sometimes a novel closes itself off and ends and a lot of times you could say, "wow if that didn’t end, if this next thing happened you could start developing it into a series." A lot of times people are disappointed that things aren’t exactly like the novel but they are completely different forms. For instance, if it just so happens that the novel is a first-person story. As soon as you say it’s going to be a tv show it can’t be in first person anymore.

FB:

No.

ED:

That means that you’re moving to some form of third person but you still want to stay very close to that character, but instead of a character thinking five or six things you have to show those things. So, some people get disappointed because when you move away from the first person, you’re losing a lot of that voice of that person’s thinking, that people are so attracted to. But there’s no other way to do it.

FB:

Talk to me about the stakes and the obstacles you’re looking to create especially in a mystery. You have to have a lot of red herrings, but how do you go about teasing out of the novels what you think would be the best obstacle and then therefore stakes that keep escalating from episode to episode?

ED:

Well, you start with the character, with what operates all the time that makes them interesting. Of course if it's in a book it’s already there. You tease out what makes them interesting, what makes them see the world differently, or notice the world from a unique perspective. The classic example is CSI. You and I would see a gunshot victim and that would be really gross for us but in CSI they would say “wait a minute they fell down in this way, therefore, the bullet had to come from here, but there’s no bullet hole there so what could explain that?” Then, there is the mystery. I think all of us are interested in what’s beneath that we see. For instance, Alice going down the rabbit hole. We use Alice in Wonderland terms in every writing session. It’s just part of the vernacular. We say “and this is where we’re really gonna go down the rabbit hole”. Where the detective goes down the rabbit hole, where the detective finds this really gruesome clue and then really really goes down deep and researches that and gets into that world. We also say “what’s on the other side of the looking glass?” and “this is where we see wonderland”. In a fantasy project, for instance, you go, “when this door opens, we see an entire different dimension”.

FB:

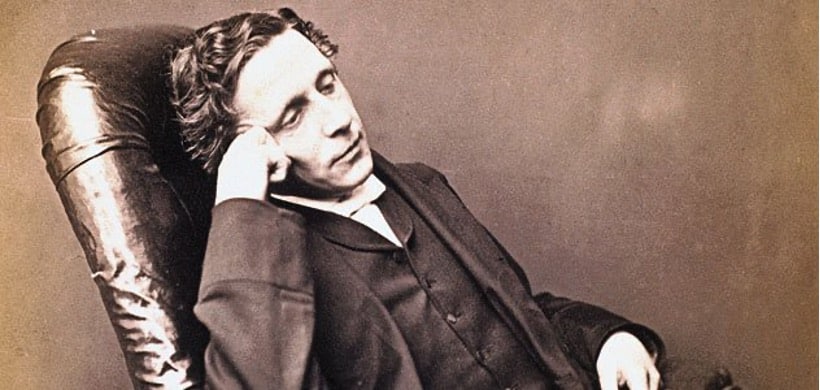

So much of it comes from a book that was written 157 years ago. It’s sort of remarkable.

ED:

In current-day fantasy stuff everybody goes “you should give JK Rowling 10% of your money” But she didn’t create the fantasy story. One of the original fantasy stories was Alice in Wonderland. The idea that Alice didn’t know precisely who she was which is identity, then she goes down the rabbit hole and then she encountered a wonderland you know. We use it in writer's rooms all of the time.

FB:

What’s interesting about the reference to Alice these days is that his books have been adapted into 197 languages like twice Harry Potter so if anything, Rowling should be giving money to the Lewis Carroll estate. Obviously, I’ve been playing in the Alice universe for a long time, but I wanted to ask you a question about that because in Alice in Wonderland, she falls down the rabbit hole and the adventure in the book is very episodic. It's not always like she has a lot of agency but she does have agency she does stand up for the injustices but she is trying to figure out who she is and I think that question is universal. Who am I? Today? Who will I be next year?

ED:

I mean generally, fantasy is about identity. Even modern-day ones, what’s the one where the guy has two parts of his life, and they're completely separate and he goes to work--?

FB:

Oh, Severance, Ben Stiller’s show!

ED:

Yes! We come back to Ben Stiller, the reason why I have my house. If you think about it, he doesn't really know who he is because part of him has been severed. So that’s an identity thing and that’s a fantasy thing but it doesn't look like Alice in Wonderland, it doesn't look like Shadow Hunters or like the Harry Potter series.

FB:

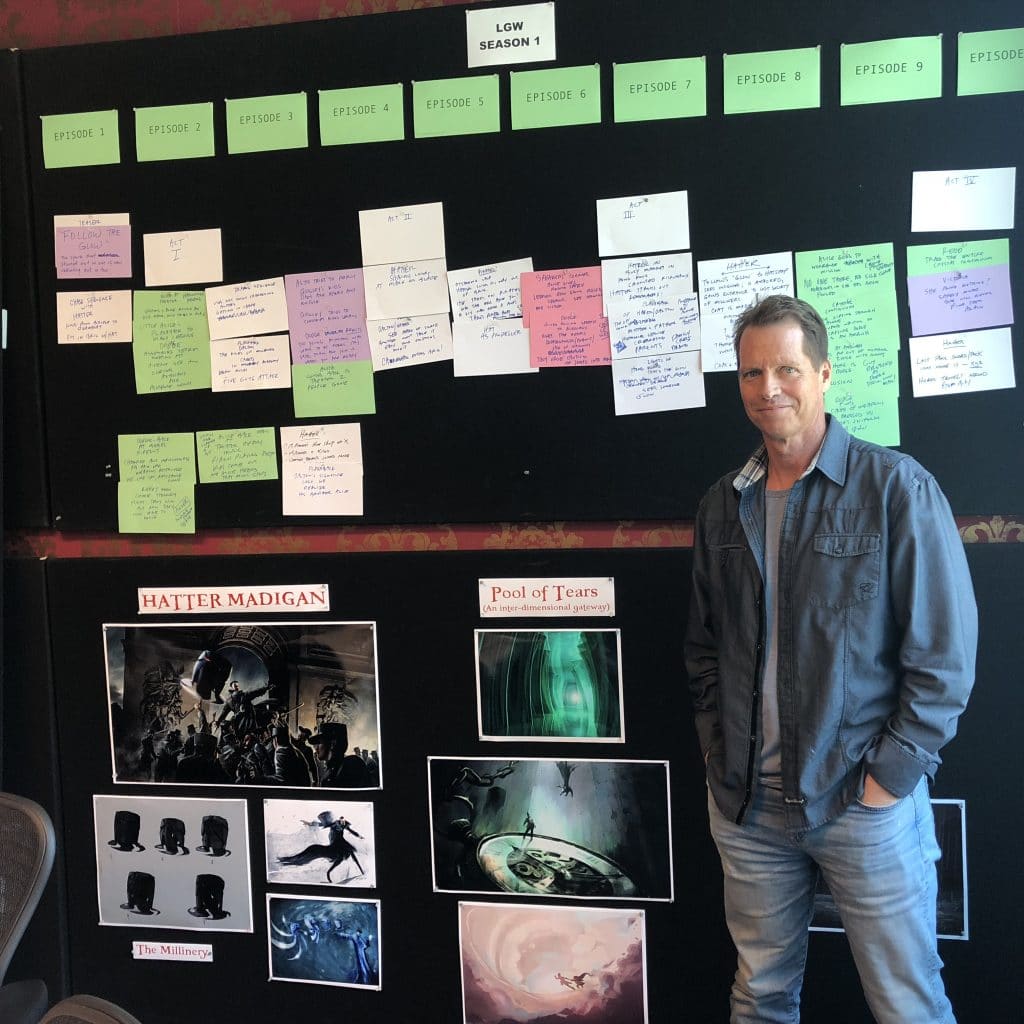

I think it’s just a powerful metaphor. What I discovered with Alice is not only is it so deeply seeded in culture, it’s referenced across all mediums. However, it hasn’t been adapted into as many TV shows as the Wizard of Oz because it’s episodic. So, one of the things that I was thinking about was how do you change that so the identity part of it is strong? So that she has a mission to go on. When you and I got together and put a writer's room together to break out The Looking Glass Wars to figure out the best strategy to turn it into a TV show— one of the things that you’re quick to point out from a casting standpoint was that we want Alice as the 20-year-old, as the adult Alice to follow. Because if you get so invested in the young Alice and then you do five or six episodes and then she’s gone that can be a bump with the viewers.

ED:

The only time I’ve seen that work slightly, in a modified version of that recently, was the Queen's Gambit. I mean that was really bold that they had the first episode with the young actress without your big star except in the very opening of the show.

FB:

What was your experience as a child or as a young adult with Alice in Wonderland. How did you first come to Alice?

ED:

Probably like everyone did. You would hear these phrases that everyone used, then you read the book. What I loved most in engaging with Alice was when you wrote the Looking Glass Wars and to me, that was like what Wicked did to the Wizard of Oz. A whole new look and a new point of view on that story. For me, that got me more into Alice than the original story because like you said it's very episodic and whimsical, beautifully written, but what I liked about the Looking Glass Wars was exactly what you were just describing. There is a drive to it and a mission to the whole thing and oppositions that you’ve set up that are so much bigger than in Alice in Wonderland. You have these wonderful Card Soldiers and Redd, and everybody built out so that you say to yourself “ah, this is a universe”. We can traverse this universe and its infinite. The coolest thing we were talking about when we were working on the series together was that you could do a flashback episode to hundreds of years before. To the whole generation before Queen Redd. There’s all that, and then what’s to become of the split between Wonderland and the real world.

FB:

Yeah and I felt like that was the most unique aspect of it, is Wonderland coming up through the rabbit hole. Because the premise is that Lewis Carrol changed the story, it suggests there’s a real story and that’s infinite. You can just continue to grow. One of the things you did in the room, and I wonder if this is something you do in every room, is you created zones. Could you talk about what that means in creating zones for taking a novel or a work to world creation, how do you see that?

ED:

First of all, every show has world creation whether or not it’s just taking place in our normal everyday lives or it's taking place in something unbelievably fantastic like Wonderland. What we're talking about with zones in television is that when you’re doing a series and you want that series to run a long time you want to have different areas to go to where there’s big areas of story. If you just have a single lead in a drama series, that person will burn out all the story in a couple of episodes. As that person meets their family of the show. Whether it's their real family or just the characters that they meet in the show. For instance, in yours, you want to be able to cut to Hatter Madigan and his whole story like, then you want to be able to cut to Queen Redd and what’s going on with her and is she looking for Alice. Then if she sends the Cat to go look for Alice, you want to be able to follow the Cat. Then you want to be able to follow Hatter Madigan’s brother. The shows that people really love, if you think about it, those are zones of story that are very rich and very powerful and can sustain a whole episode. So when you’re world-building in something complex and large like Looking Glass Wars you want to establish all these different areas that you can go to so that the audience is going, “Oh I want to see the conclusion of this story, now we’re over here.” And then “Oh my god what’s happening here?” You want to start a lot of fires.

FB:

I’m thinking about the Looking Glass Wars season one a little bit differently now. What do you think about the way that they set that up Queen’s Gambit? Is that possible for the Looking Glass Wars? Because the premise of Alice meeting Lewis Carroll and seeing him change her story—that’s the high concept moment which everybody can recognize as, "oh this is why this is different." This is why this should exist. Especially in culture now where facts are not facts, what’s real and what’s fantasy. It feels thematically like this is an interesting spot but you have to spend some time with her as a young girl and meeting Lewis Carroll and seeing how Lewis Carroll gets it wrong and how it affects her. That would change the idea that we started with which was she was an unreliable narrator.

ED:

In fact, Lewis Carrol was the unreliable narrator.

FB:

Exactly. I’m wondering if you were choosing between those two, having the high concept and getting it out early vs. holding back and using the unreliable narrator with trust that we can flashback to the coup later and to a reveal that Lewis Carroll did in fact get it wrong. What is your take today?

ED:

Well, a lot of it has to do with sales. Meaning that, and it depends who you are. The Queen's Gambit was really a risky thing to do because you have a big star, she wasn’t a big star at the time but she became a huge star, Anya Taylor Joy. Now story-wise, you’re absolutely right, it would be great to spend time with Alice, especially like in a first episode, and do a prequel to the whole series. In the business of television very often they want you to do the series and not the backstory of the series but now the world has been opened up to different ways of telling a story and I could see that the first episode could be. You could go back in time. You could start with the adult Alice that is your star very much like in Queens Gambit and you could flash back to her young life that she barely remembers because she remembers Lewis Carrol's version of her story.

FB:

Exactly and everybody keeps telling her that’s the real story and she’s the muse to that. The pain came from that as a young girl, she pushes away.

ED:

Right.

FB:

Are there other references to Alice in Wonderland that you identify with? Or that you have put together recently?

ED:

I see it in so much in everything.

FB:

In Stranger Things I just saw it, it’s everywhere.

ED:

By the way, this is the paradigm. Monsters inc. Ok, it’s a completely animated movie. It’s in our world, little kids getting scared by monsters, that’s our ground zero or home base. That’s the buy of the movie. Then there’s this whole sequence with all the doors traveling in space. That’s Wonderland.

FB:

Yeah exactly.

ED:

That’s you transported into another world.

FB:

If you were to reimagine a classic for television, like how many times have they done Sherlock Holmes? It’s amazing.

ED:

They just had season two of Enola Holmes.

FB:

And it did fantastic, my daughter loves that show. Is there one out there? Could you do Treasure Island? Anything come to mind in terms of something that you read as a kid that you would be interested in reimagining?

ED:

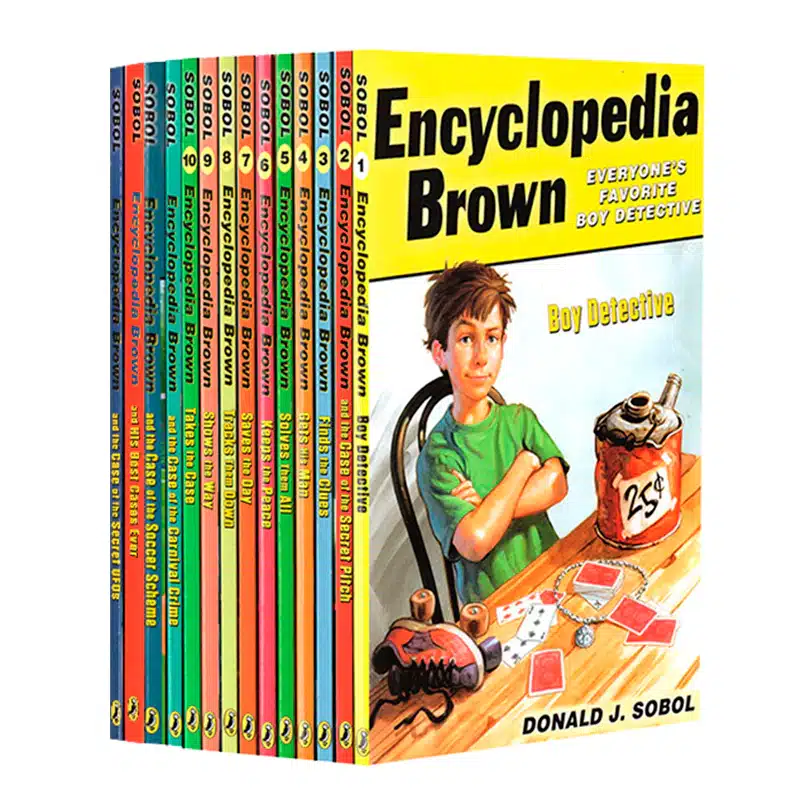

The first thing that pops to mind is a kids book that I loved. It goes right to the work I’m doing now. When I was young I loved the Encyclopedia Brown books. It was a kid detective, and he was just real knowledgeable about science and all this stuff. He would figure things out. It was a trigger, a gateway drug for all these novels that I read now. I’d remake that with a woman detective.

FB:

Is there a way for us to contextualize this whole conversation? What is it about Alice that resonates with culture as an iconic character, as a fantasy book? The feeling of wanting to escape, to having an identity?

ED:

‘Cause Alice kind of rebels, right?

FB:

She does.

ED:

It’s deep in the genes to want to rebel against authority. Then the other thing is the idea that everything feels in some way that their life is kind of humdrum or mundane. Even people whose lives aren’t humdrum and mundane, to them it’s their lives. There is this sense that, what if there was something else? Like another dimension or something where a whole world opens up. The same guy who said television is a government and movies are war said that when you have a child it’s like an undiscovered country of love.

FB:

Yeah, it’s so true. To wrap this up, let me just ask. What is the most requested piece of advice as a teacher, what do you think inspires the students? What do you think they most often ask?

ED:

They most often ask this, “how do I write something successful?”

FB:

Right.

ED:

Which is not the right question.

FB:

Clearly.

ED:

The right question is, how do I write something that is personal to me? Something that can…

FB:

Can connect?

ED:

Can connect. I call it the bridge and that is really the core of Alice, right? There’s this girl and we sort of understand her life and we see her and then she goes into this other world and we go with her and it's a bridge to another world. If you as a writer can build that bridge and bring people along on a journey that’s what leads to success but it comes from you and it comes from the character. There are a lot of people who think I’m going to create a world and then stick a character into it.

FB:

Yeah that does not work.

ED:

That does not work, and world creation is following a character and then discovering a world.

FB:

If you and I were musical we would take that phrase, a bridge to another world, and we would write a hit song. Thank you so much for joining me today.

ED:

My pleasure.

For the latest updates & news about All Things Alice, read our blog or subscribe to our podcast!