All Things Alice: Interview with Dr. April James, Creator of The ALICE Way

As an amateur scholar and die-hard enthusiast of everything to do with Alice in Wonderland, I have launched a podcast that takes on Alice’s everlasting influence on pop culture. As an author who draws on Lewis Carroll’s iconic masterpiece for my Looking Glass Wars universe, I’m well acquainted with the process of dipping into Wonderland for inspiration.

The journey has brought me into contact with a fantastic community of artists and creators from all walks of life—and this podcast will be the platform where we come together to answer the fascinating question: “What is it about Alice?”

For this episode, it was my great pleasure to have wellness educator and opera singer Dr. April James join me as my guest! Read on to explore our conversation, and check out the whole series on your favorite podcasting platform to listen to the full interview.

Frank Beddor

Dr. April James, it's so nice to have you on the show.

Dr. April James

Thank you. It’s so nice to be on the show.

FB

Your approach to Alice in Wonderland and wellness is really interesting. The way you use Alice and the five steps is very clever. I’m excited to get into that.

AJ

Thank you. I use them as they come to me.

FB

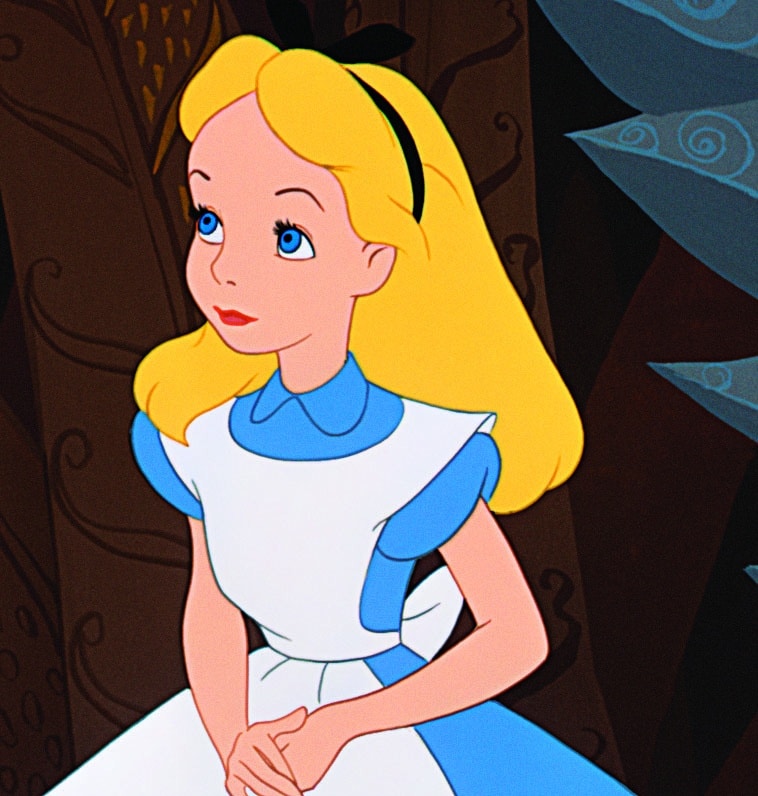

I want to start with a question about your introduction to Alice in Wonderland. Your website states it was Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland, which is very unusual that his film would be the introduction, given how long Alice has been in pop culture. Most of the time, people either read the book when their parents introduced them or they saw the Disney animated movie. Before you saw Tim Burton's movie, what did you know of Wonderland?

AJ

I didn't know a whole lot. I might have seen the animated Disney film when I was a kid. I'm sure it was on television and it might have flitted by my consciousness. But I never read the books as a kid. The only bit of Lewis Carroll I really knew before seeing the Tim Burton film was the poem “Jabberwocky.” I took a Victorian literature class in undergrad, at Queens College, and we had to read that for an assignment. I loved that poem because I was into medieval stuff. I had taken Arthurian literature classes, and I was really big on knights in shining armor. The mock Old English style in which “Jabberwocky” is written really appealed to me and I just loved that. But I didn't really know anything else about Lewis Carroll or Alice's Adventures in Wonderland until after that Tim Burton film.

FB

Tell me about the experience of seeing the Tim Burton movie and relating that to “Jabberwocky” and its author. What was your reaction to the movie and where did you go from there?

AJ

I almost didn't see the film. I was at a really difficult point in my life. I returned to New York after getting my doctorate up at Harvard. I moved back in with my mother because that's what you do when you can't afford to do anything in New York. I came to call it a “Decade of Awfulness.” I was trying to build an opera career, some kind of creative career, but my mother kept having health issues and we kept having family friction because I have an older brother who was creating havoc at a distance with her. By the time March 2010 came around, I was borderline depressed and nothing was really working. But I was a member of the Actors Work Program, which is part of the entertainment industry unions, and I'd met someone who was a member of SAG. She had passes to the then newly opened Alice in Wonderland and she invited me. I thought, “Well, I don't really know anything about Lewis Carroll. I don't really care about Tim Burton and Johnny Depp.” I hemmed and hawed but eventually, I decided to go. I’d not seen a 3D film and I figured it'd be worth the price of admission.

It just totally blew me away. The moment the music came up and the lights came up on the screen, I felt something reawaken in me. I'm a singer and a classical musician and the music caught my ear. There was some mystery and some magic and wonder and innocence in there. Then the visuals started to reach me and as Alice was going through her story, I kept finding resonances with my own life. Adults telling you what to do, “We think you should do this. Everyone should do that.” “What, I don't get an opinion here?” Then what really got me was the Mad Tea Party scene where Alice comes out of this clearing and there's a table with the Dormouse and the March Hare. Hatter’s at the end of the table asleep in his chair. As he awakens, he sees Alice coming out of the clearing and his face fills with delight. The moment his face filled the screen, I heard, inside my head, this British-accented voice go, “That's me.” I asked, “Me who?” No response. I just went back to watching the film and by the end, I came out of that theater and I felt this buzzing inside of me. Something reawakened in me. That's when I started being obsessed with Hatter, Lewis Carroll, and all things Alice.

FB

Had other films evoked such a strong reaction in you previously?

AJ

Not as strong as that. I had seen films that I just loved. When I was a teenager, I was really into the Beatles and I saw A Hard Day's Night. I'd sing the songs at the top of my lungs. Something like that.

FB

Alice in Wonderland resonated with you to the point where you have a career built around wellness. You said you went back and started thinking about the Mad Hatter and all things Alice and Lewis Carroll. Where did the journey take you after the movie? Did you read the book? Did you see a documentary? What happened?

AJ

I read all the books. I read both of the Alice books and “Hunting of the Snark” and Sylvie and Bruno. I read biography after biography about Lewis Carroll and the more I learned about him, the more I fell in love with him. Especially reading the collections of his letters, I felt like I was encountering a long-lost uncle. That's how I felt and still feel about Lewis Caroll. He gets me. He gets children. He gets people. If we're in a foul mood, he knows how to pull us out of it.

FB

There are two camps when interpreting Lewis Carroll's books. There's the interpretation that it’s whimsical, very nonsensical, and magical. I suspect you subscribe to that interpretation because of the work you do. However, on the other side of it, people really look at Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as dark and twisted. The terror of being out of control in your body, growing and shrinking, and things like that. Were you able to see both sides of it reading the text? Did you have a really strong first impression of where Lewis Carroll was coming from?

AJ

My impression has always been that he's coming from the whimsical, nonsensical side. The good side, the magical side of everything. He was very interested in imagination and he was very spiritual and connected to God. This love of life permeates his best works. Joy and love are positive emotions that connect us to the good that's in the universe. The good that lies at the heart of all of us.

FB

I agree with you. The first word you used was imagination and that's what struck me about the text. As an adult, writing for adults and for kids, I always thought it was about keeping that childhood wonder and imagination going and how we lose it as an adult. In a lot of ways, Lewis Carroll was a very rigid man who taught mathematics, yet he was flipping to the other side with his writing. One part of your wellness program is about getting back to that youthful, imaginative joy that you always lived as a kid.

AJ

Exactly. One of the sayings I like is, “It's never too late to have a happy childhood.”

FB

Excellent. I love that.

AJ

Some people didn't necessarily have the happiest childhood, right? I had a good childhood but I had a rather responsible kind of childhood, too. “You're going to go to school and you're going to learn, and you're going to do this and this and this.” College was never a question. I was going to college. But I always wanted people to play with. My brother is way older than I am so he wasn’t around when I was a kid and there weren't any other kids my age in my neighborhood. So I really had to use my imagination a lot growing up. Creating worlds of wonder for myself. As we get older, for some reason, society tells us not to be playful, or we get this idea that can't be playful and do good work, which is absolutely not the case. I had to relearn that.

FB

Kudos to your parents because education is really important. You went to Harvard, which is exceptional as well. Tell me what your household was like in terms of the educational part of it versus the playful part of it. You said that when you were on your own, you were imaginative. Was there a crossover, or did you carve that out yourself and your parents were by the book?

AJ

My parents were both teachers. My mother was a special education teacher, and my father was an attendance teacher, which is like a truant officer, but you work for the Board of Education. So they were both really responsible and interested in learning. My mother comes from a family of teachers. Her mother was a teacher and her sisters were also teachers or librarians. It's a very educated family. I was always expected to go to school and do well, and it wasn't hard for me to do that. I liked learning. I loved reading. As a kid, I was in the library all the time, pulling out whatever interested me. I remember reading The Chronicles of Narnia series when I was a child.

Harvard was actually the first time I started to believe in myself and my ability to do anything. I'm a singer by inclination more than training. I've always loved music. I had these two tracks going in my life. There was the liberal arts education track, but I loved music, and I wanted to study music. However, I was discouraged from doing music as a major during my first bachelor's degree at Queen's College. I understood that, so I studied communications, and I went into TV and publishing. I hated it. I didn't like the field. After a couple of years of job to job to job, I was laid off right before Thanksgiving, and I said, “You know what? I'm going to go and study what I wanted to study before. I'm going to go back to Queens College and study music, and we'll see how it works out. That’s how I ended up at Harvard.”

FB

Good for you.

Do you think that was a smart thing for your mom to say to you, versus saying, “Follow your passion”? I find that to be really difficult. I have two teenage kids, one who just went off to college and knows what he wants to do. He doesn't want to be in entertainment, he wants to be more in business. But my daughter, she's going all over the place.

My father was a real entrepreneur, a risk taker, and he was like, “Yes, go do it.” I started off on the ski team and it seemed like a ridiculous idea that I would ever make money or that I would be good at it. And I would have to not go to college, where I was going to go to college part-time, and my mom said, “Absolutely not.” My dad, however, said, “Absolutely do it.” I wonder how you feel about your mom’s advice and, if you were giving that advice to yourself, what would you say?

AJ

It’s taken me a long time to get over my mother's advice. I realize that she was right in a way and she was wrong in a way. My father, even though he was an attendance teacher when I was growing up, was laid off from the city in the 70s. He was also an entrepreneur and he started his own driving school after a time. So I have both this toeing-the-line thing and the entrepreneurial thing going. Now, I understand and I actually appreciate my mother's take on the arts career-wise. I wish she'd been a little more nuanced in what she had said.

After I got out of Harvard, I tried to have an arts career. My research was on women composers and operas composed by women. I started my own opera company and it was so difficult. Even if my mother had been in perfect health and we'd had perfect stuff going on in the family situation, it still would’ve been so difficult. I just said, “You know, what? I don't want to be a full-time artist.” I got to that point.

But I understand what my mother was saying. What she was saying was it's very difficult to make it in the arts. You can, but it's not as clear a path as getting a nine-to-five job somewhere or getting a teaching degree and then teaching. I understand where she was coming from.

FB

It’s not just talent. Talent can only get you so far. If you’re an actor, you have to be so driven that what you're saying to yourself is, “I don't care if I do community theater, I am going to act. I am not thinking about being a movie star. I just need to be on the stage. It's how I live and breathe.” If you don't look at it that way, then you're not going to make it. You're doing it because you can't do anything else.

AJ

That's exactly it. I love singing. I sing all the time. I wake up in the morning, and I'm singing. During the day, I'm singing. I'm singing Bach. I'm singing Handel. I’m singing Mozart. All this gorgeous music that I love. I don't have to be out in front of people to do it. I came to that realization. I do need to be with other people. There's a pianist I'm working with now. I sing in choirs. I've done some recordings, but I don't have to be in an operatic role on stage.

FB

You found your way in terms of combining a lot of different interests. You have your website and your wellness program, the ALICE Way, which is how I originally found you. I love the way you describe helping adults rediscover their natural joy and playfulness so they can better navigate life's ups and downs. Alice in Wonderland is so deeply rooted in culture and brings lots of joy and amusement to people, and you've attached these five steps. Could you tell us the five steps, how you came to them, and why it's been effective for people?

AJ

Alice is not just the name of the heroine of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. For me, she also gives her name to the acronym for the five steps. They’re equations. “A” equals “Awe plus Authenticity.” “L” is “Love plus Levity.” “I” is “Inspiration plus Impossibility.” “C” is “Courage plus Clarity.” “E” is “Exercise plus Expressivity.”

FB

Beautiful. There's a double meaning for everything. Then you sign up for your program and you work your way through the acronym. People want awe in their life and they want to be authentic. To be authentic, you have to know yourself. And to know yourself is one of the themes of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Do you tie the story and Alice as the protagonist into the exercises?

AJ

That's exactly what I do. I have an online video course and I also do this in person. I'll talk about the video course as that's most accessible to people. I divide it up into chapters plus an intro and a conclusion. In the chapter on “A” for “Awe and Authenticity,” for example, I do a video where I introduce the topic by reading something from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland that relates to awe. Then I tell a story from my life that connects to the same concept of awe. Then there's an exercise, a separate video, on how you can experience awe in your life. Most of the videos are under 10 minutes. I also have a 42-page playbook to accompany the course so people can do written exercises along with each chapter of the ALICE Way.

FB

Is there any crossover between the text that you're referencing and Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland? Was there anything in his movie that you carried over for your program because you liked it? Or do you stick with the original, Lewis Carroll text?

AJ

I keep with the original. The original is the reason why the Tim Burton film is so effective. So let's reference the original work. I really want to encourage people to engage with Lewis Carroll and engage with his work. The ALICE Way is not just about me. I want adults to rediscover joy and I want to have other people to play with. But it's also about appreciating this man who was just such an incredibly loving soul and left us such engaging, enriching, and magical works that can still affect us.

FB

That are still important 150-plus years later.

AJ

It’s amazing. How many times in a week do you hear the phrase “down the rabbit hole”?

FB

I bet you have heard it a lot more since you saw the movie. Before, you probably didn't even know it was connected to Alice in Wonderland.

AJ

Exactly. I don't think I ever knew it was connected.

FB

You use the word joy. Joy is having a moment in society and culture right now. Why do you think that is?

AJ

Joy is one of the most underrated emotional states.

FB

It's true. It's one of those things you forget as an adult. Speaking for myself, I'm usually waiting for some something really outstanding to happen, like having this interview, which will create great joy for me. As opposed to finding joy in the little things when you're just going about your day, like a really amazing cup of coffee. I think we should be enhancing joy in life. There's imagination and there's wonder and there's awe, and a lot of the things you talked about, but living with joy is a nice state if you can get to it.

AJ

Sometimes people think it's unapproachable or unattainable, but it's not it. I maintain that joy is our natural state. That's something Charles Dodgson understood. His cultivation of these child friendships and his love of telling stories grows out of a recognition that children come in joyful. We come in joyful. Dodgson was the eldest male child in a family of 11, so he got to experience that with his brothers and sisters. He was like the family entertainer. He would make up things for his siblings. I think that's where his love of the theater came from. He was able to access imagination and joy and saw other people who could also do that regularly.

There's something divine about joy and I think Charles Dodgson understood that joy and love come from the Divine Well. That's where we come from. That's the source we go back to. So let's keep that in our lives because that is the actual fuel for our lives. Good energy is the real fuel that keeps us healthy and that's why we need to cultivate these good emotions, speak good words, take in good thoughts, and do good deeds. That's what keeps us healthy as individuals and as a society.

FB

You certainly seem to be living the ALICE Way. At the same time as Alice and Lewis Carroll, there's a secondary character that has somehow found her way into you, is that correct?

AJ

Madison Hatta, Sonneteer.

FB

Can you tell us a little bit about her and her birth?

AJ

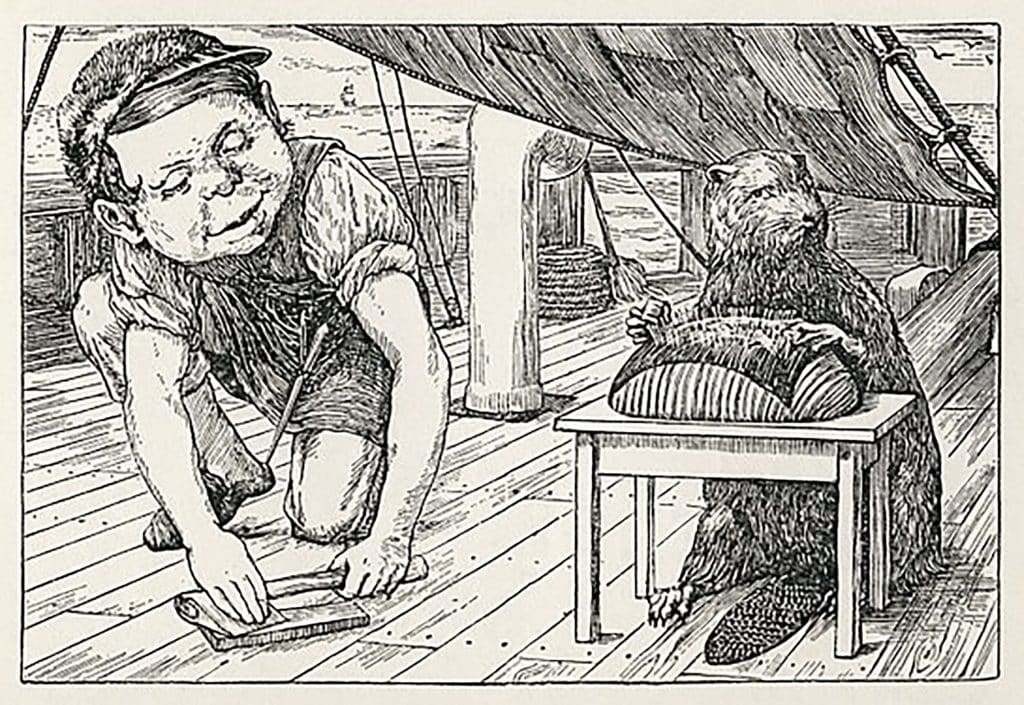

This is what I mentioned earlier, the voice that came to me during the Tim Burton film. It was about a year later and I was obsessed with finding images from the film to use as wallpaper on my Mac. I came across one that had a picture of the Hatter and a poem on the side, which was written in a Hatter-ish voice. So I'm looking at it and then that British-accented voice piped up inside my head again and said, “I could do better. It's not even a proper form. It needs to be a sonnet.” I hadn't written one of those since I had a Creative Writing class at Queens College years previous. But I had been working with angelic energies a couple of years previous to that so I recognized this as a directive from a spirit.

So I got out pieces of paper and a pen and I started writing. Then I started laughing because 15 minutes later, we had:

"If I were not mad, what on Earth would I be?

It is an unlikely prospect I'm sure you'll agree.

Those voices that whisper when no one is near

Their meaning is all too entirely clear.

I love out-of-turn.

I sing in the rain.

To me, this is custom,

To others, insane.

My past is a mystery shrouded in dreams concealed by blue starlight and moonlit by streams. My present meanders up on common roads.

And as for my future, who knows what it holds?

My friends, they're a mixture of whimsy and wise who come round the bend to drink tea in disguise.

In a world where one plus one equals three,

If I were not mad, who would I be?"

Came right out of my pen. That's how I wrote it. Then the name Madison Hatta, Sonneteer came right out of the pen afterwards.

FB

That was really brilliant. I can see the connection with Lewis Carroll and how strong it is in terms of the brilliance of that poem and how relatable it is to his work and to your own creativity. Thank you so much for sharing that. Have you published that somewhere or where would somebody find that?

AJ

That is in a little chapbook called Madison Hatta’s Book of Unreasonable Rhymes. That was published by Moonstone Press in Philadelphia back in 2015. They may still have some copies available. The ALICE Way is a course but I also plan to have it as my second book. I published my opening essay from that book, “Down the Rabbit Hole,” on the Gulf Coast Writers Association website. It won third place in the Non-Fiction category of their 2024 Writing Contest.

FB

Amazing. How cool.

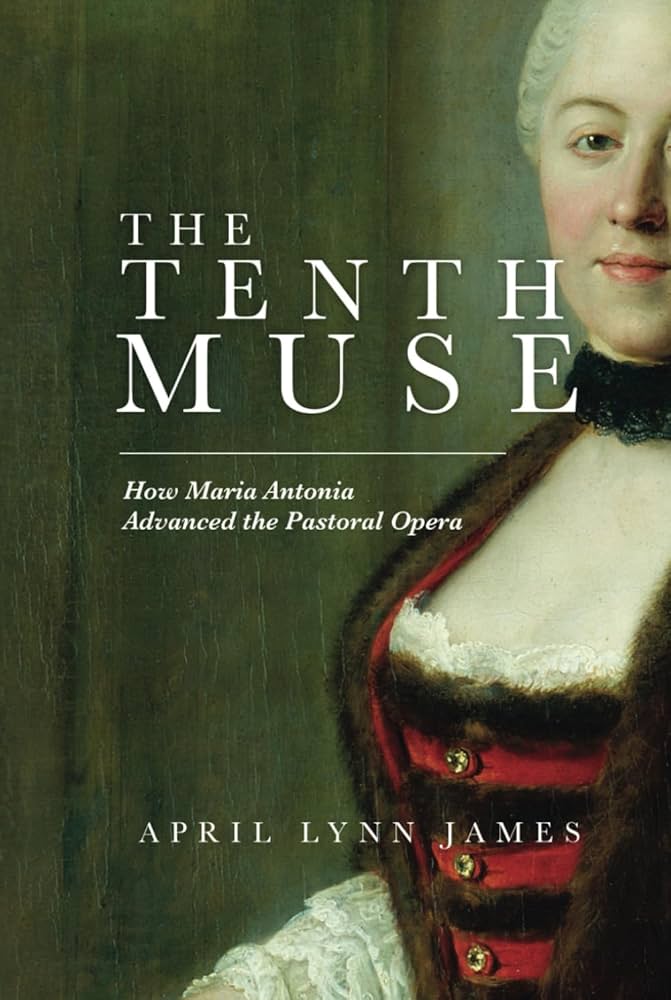

Your first book was The Tenth Muse. Tell us about your first writing experience and what the book is about.

AJ

The Tenth Muse: How Maria Antonia Advanced the Pastoral Opera. A pastoral opera is shepherds and shepherdesses in love. That's the simplest explanation of it.

Maria Antonio was a noblewoman who lived in the middle of the 18th century. She was well known at the time because she was a composer, poet, and singer, as well as a patron of the arts who wanted to turn the German Electorate of Saxony into the fine arts capital of Europe. She composed two operas. She wrote the music and the lyrics, and she sang as the lead. This is extraordinary for anyone of any time to do, but particularly at that time and for her to be a Princess. People wrote poems to celebrate her life. They named their kids after her. In fact, one of the people named after her was the Queen of France, who everyone has probably heard of, her cousin, Marie Antoinette.

FB

Wow, that sounds like it could make a good movie. She seems like such a fascinating character and so ahead of her time.

Is there anything else you would like to talk about regarding your ALICE Way program? I really hope people will check it out. It's been so much fun talking to you about Alice in Wonderland. I really appreciate your taking the Mad Hatter and turning him into Madison Hatta. I named my reimagining of the Mad Hatter, Hatter Madigan. We both need that “mad” somewhere in the name. Yours was divine. She came to you. I think mine came up from below.

AJ

I call Madison the guardian angel of my sense of humor. She came at a time when I was starting to lose my sense of humor. I think we all need that reminder.

FB

Thank you for offering this wellness program and for the incredible amount of optimism you shared. Most importantly, I'd like to end on the joy that you communicated and the joy it's been having you on the show. We wish you the best of luck and thank you for taking the time to chat with us.

AJ

Thank you for having me on your show, Frank. It's been wonderful chatting with you.

For the latest updates & news about All Things Alice, please read our blog and subscribe to our podcast!