Hope Renewed: Princess Alyss Embraces Her Destiny - Part 4

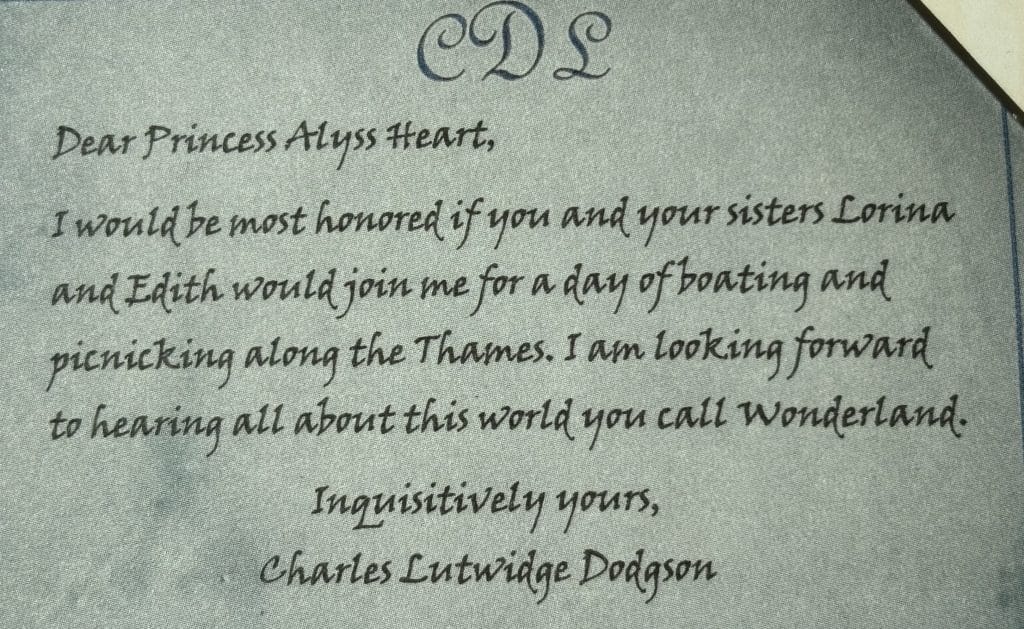

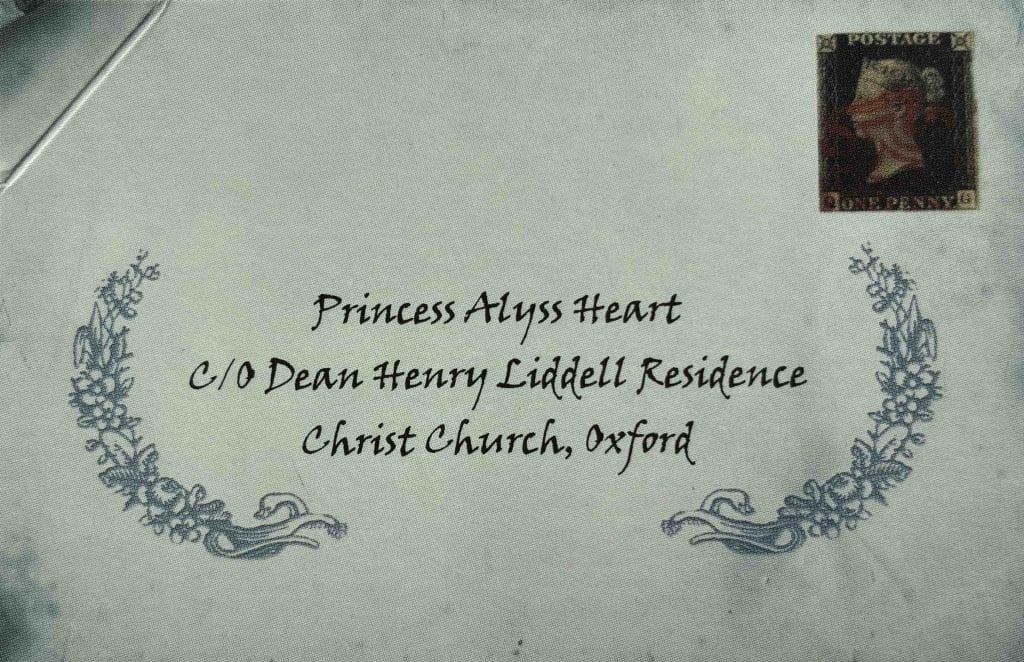

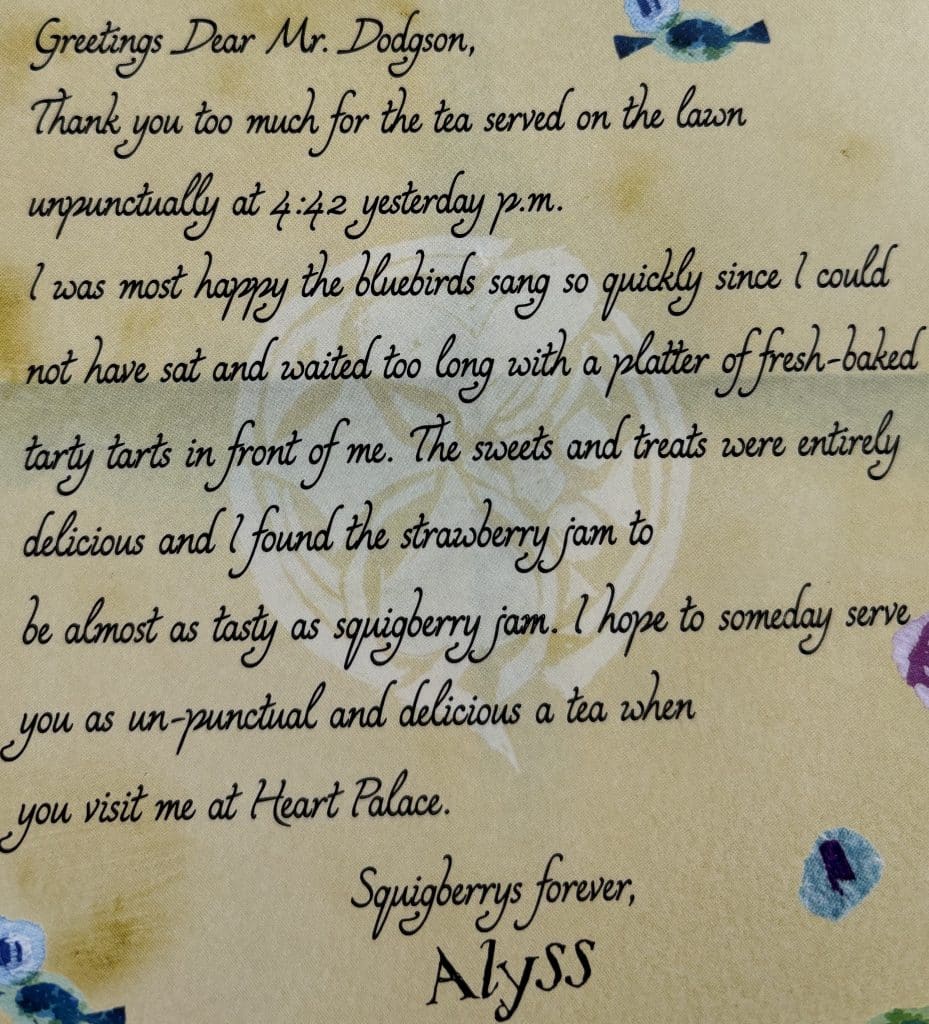

Back in 2007, we collaborated with noted Alyssian historian Agnes MacKenzie to publish Princess Alyss of Wonderland, a stunning collection of letters, journal writings, and art from Her Royal Imaginer, Princess Alyss Heart. These breathtaking documents chronicled the incredible childhood of Wonderland’s exiled heir apparent and future hero of The Looking Glass Wars.

Part One spanned Alyss’ flight from Wonderland and how she survived her first days on the rough streets of London. In Part Two, Alyss recounts the horrors of the notorious Charing Cross Orphanage and her disappointment at being adopted by the unimaginative Liddells. Part Three follows Alyss' pain and indignation when she is betrayed by her good friend, Lewis Carroll.

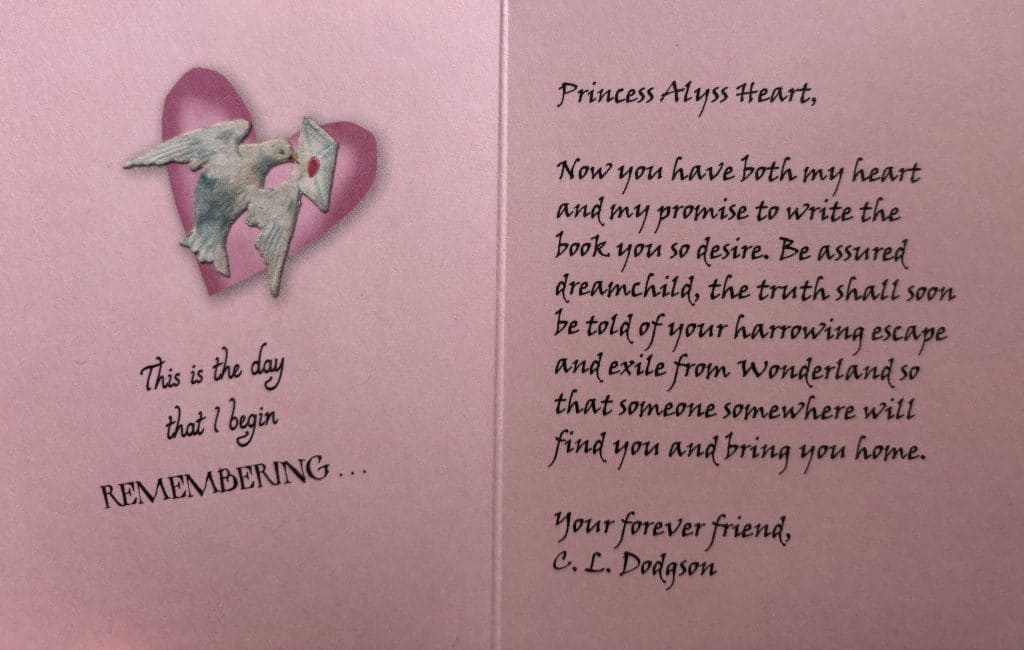

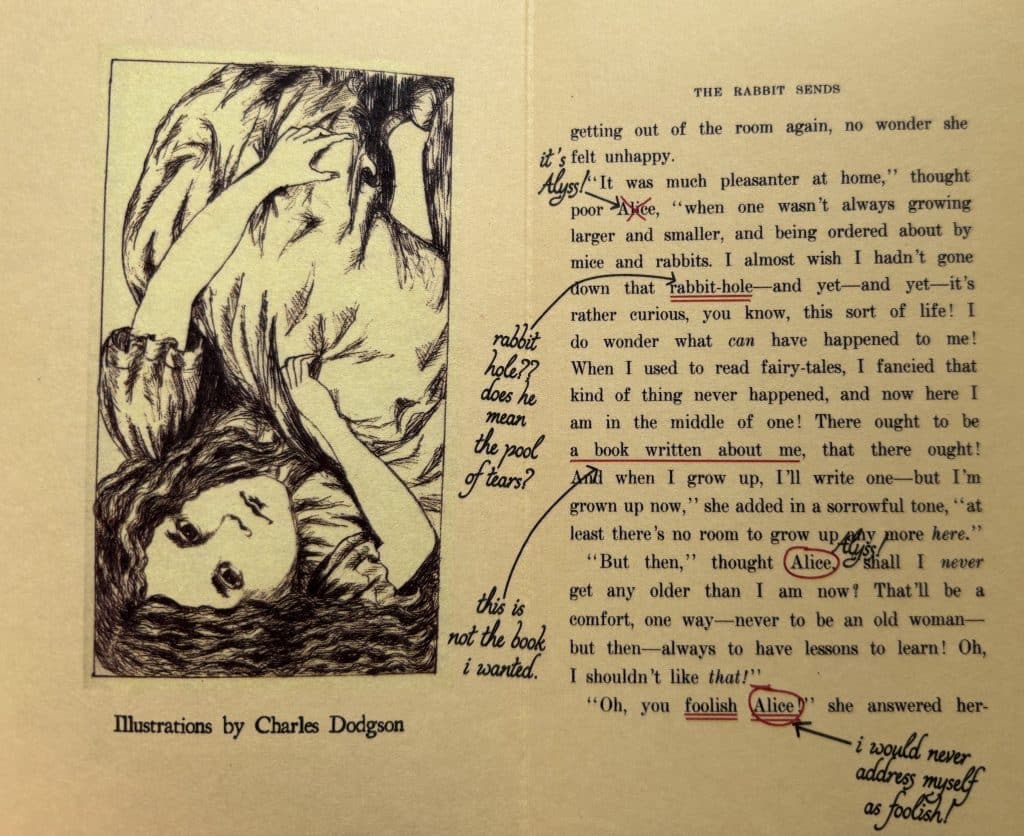

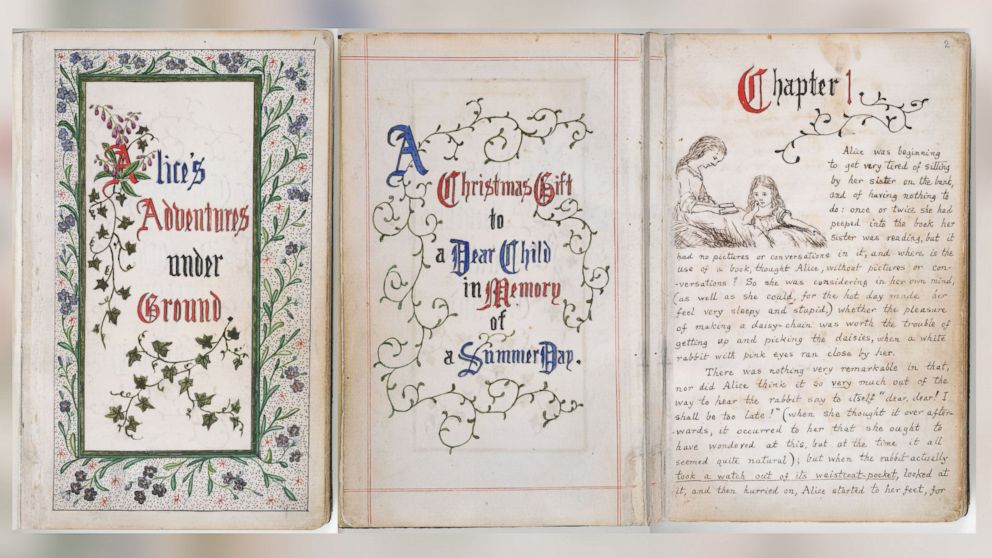

When we last saw Alyss, she was slipping into despair over the gross falsehoods contained in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” She thought Lewis Carroll believed her when she told him about Wonderland, Redd, and Hatter. But he had just twisted her words and now she had to admit that “Alice” had won.

Yet Alyss wouldn’t be down for long. A surprising message from home soon arrived and helped remind Alyss of who she was meant to be…

(*As always, I am indebted to the tireless and exhaustive research of the eminent Wonderland historian Agnes MacKenzie. Her dedication has helped keep the true story of Queen Alyss alive!)

Diary Entry - October 19, 1865

Since the BETRAYAL, I have been in the darkest of moods, unable to smile or even enjoy a delicious toffee twist. Wanting to be alone and as far away as possible from any mention of “Alice,” I decided to walk to a meadow where I often go to think about Wonderland when a ray of brilliant, almost crystal, sunshine cut across the meadow and all of the flowers lifted their faces skyward and began to sing. It was the most wondrous sound I had ever heard. Unbelievable, perhaps, to anyone from this world but for me. I was immediately aware of the presence of Wonderland.

Diary Entry - October 19, 1865 (continued)

I now realize that flowers are the link to Wonderland and that they are the purest receivers of Imagination. Everything and everyone else I have encountered has been rather lacking in spirit, form, and IMAGINATION compared to what exists in Wonderland. In this world, animals are treated as if they have no mind of their own and respond by being inarticulate while in Wonderland so-called animals hold public office and play instruments. And the buildings here are so SQUARE and SOLID. Who could bear to live in a box all of their life? Boxes are for transporting items, not a place to live, laugh and dream! My mind continued to race as I recalled the creatures and streets and shops of Wonderland. I became so dizzy with color and space and Imagination that I immediately began painting and by teatime had covered every inch of my bedroom walls with art.

Diary Entry - October 27, 1865

I was in my room today when suddenly and very clearly I heard Bibwit Harte’s voice call out to me, “Princess! You must check your pockets!” What could it possibly mean? Thinking hard all day I went to each of my pinafores and coats and dutifully checked every pocket. Nothing but one stale peppermint twist which I immediately ate. Hmmm? It was very puzzling. And then I knew! My birthday gown from Wonderland! I went to where it was stored in the closet trunk and pulled it out. I checked every pocket. NOTHING!!!

But wait…

Letter from Princess Alyss to Royal Tutor Bibwit Harte

Most Honorable and Learned Bibwit Harte,

Of course, it would be you, the knower of all of Wonderland's secrets past, present, and future, who would find a way to contact me. Unfortunately, I possess no such knowledge so I am forced to use the British Post. Dear, dear Bibwit Harte you have no idea how thrilled I was to hear your voice and receive your message. But it wasn’t until I remembered the secret pocket sewn inside the right wristband of my Birthday gown for keeping treasures that must never be lost that I made my discovery. I unbuttoned the tiny pocket and immediately felt the cool, clear roundness of the Imagination Sphere! I remembered how you would leave the sphere on my pillow whenever you wished to summon me for Imagination Training. Now that I have found the sphere I will begin training immediately. Expect updates.

Your most promising student,

HRI Alyss

Diary Entry - November 22, 1865

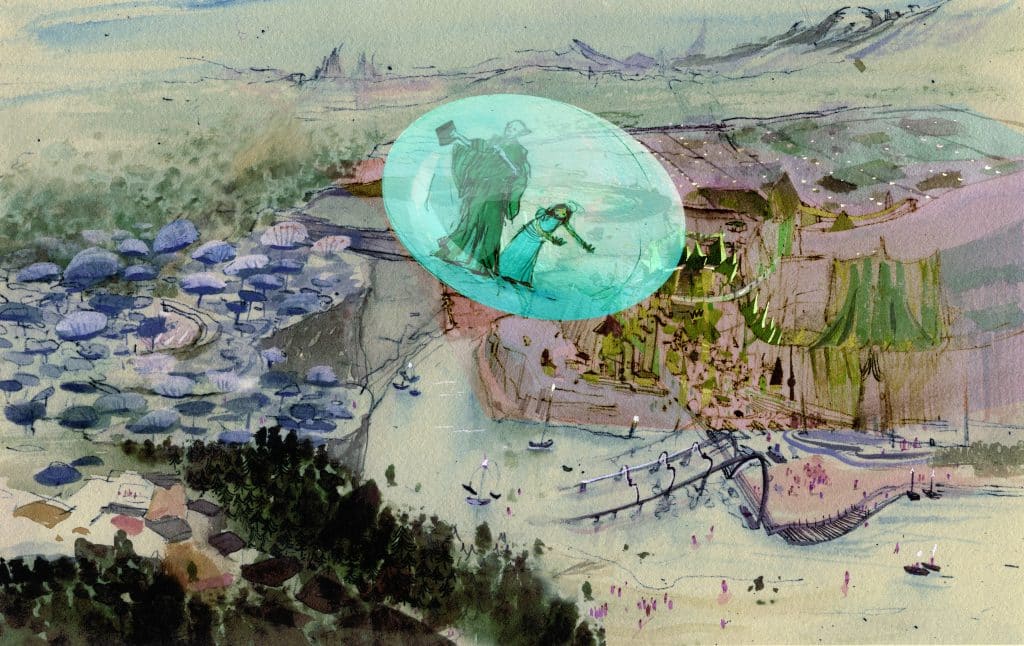

After training all day with the Imagination Sphere, I fell asleep and immediately began to dream of traveling with Bibwit over Wonderland in an enormous illuminated bubble. As we floated to all seven corners of the land, Bibwit told me the Secret of Finding Your Imagination. I have tried to record them exactly as he told me because I am certain this information is vital for everyone.

The Secrets of Finding Your Imagination

What you see behind you is as important as what you see in front.

Do cartwheels twice a day while humming your favorite song.

Laugh very loud if you cannot remember something.

Walk backward if you are in a hurry.

Never hurry to something unpleasant.

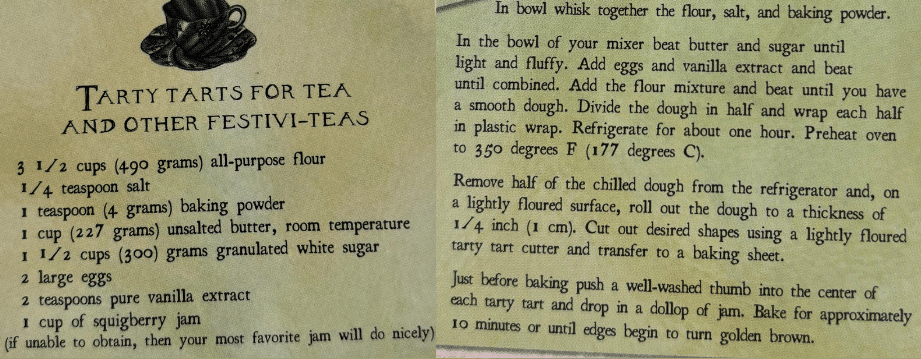

Eat something delicious before bed.

Look out the window immediately upon waking and say hello to the twin suns.

Bid the Thurmite moon goodnight before sleeping.

Remember to dream.

Dream to remember.

Tickle your imagination when stuck.

Agnes MacKenzie

Dear reader, you see before you one of the most valuable documents ever given to our world. It is with the utmost sincerity that I encourage each and every one of you to practice the secrets revealed here and be prepared to experience an imagination that has no bounds.

Letter from Princess Alyss to Royal Tutor Bibwit Harte

Most Honorable and Learned Bibwit Harte,

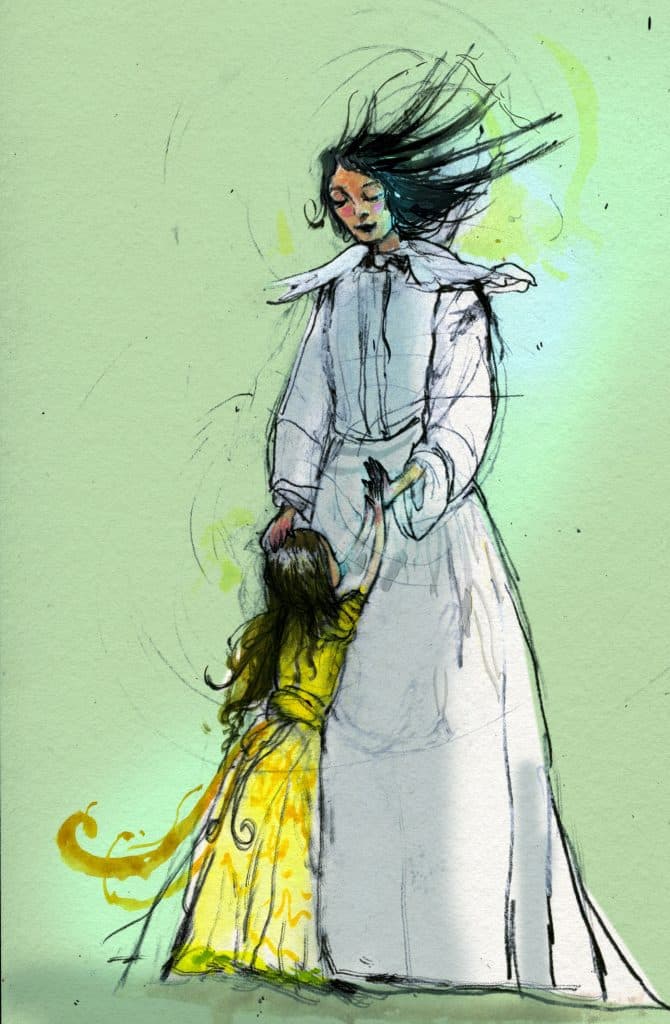

I have been faithfully training with the Imagination Sphere three times a day and am very happy to inform you that my Imagination is becoming very powerful. The skies are bluer and the sun brighter and people smile much more now. When I see with my Imagination I see things that are hidden and I am able to assist others with their searches. For instance, Lorina lost her favorite doll and by simply imagining where she could possibly have left it I was immediately able to find it. And most importantly, I breathe in the air and imagine that it fills me so much that I can float above the trees and see all the best puddles. I will continue training each day and hopefully will find the puddle that will return me to Wonderland in time for my next birthday. I have also learned many new ways of imagining that are useful here in this world. Painting and drawing are very much like imagining in Wonderland, only here I use a brush with colored paints or a piece of lead to make what I need to see or feel or remember. My imaginings must stay on the page here in this world but they feel no less real to me than what I once imagined in Wonderland.

Your forever grateful pupil,

HRI Alyss

Diary Entry - January 1, 1866

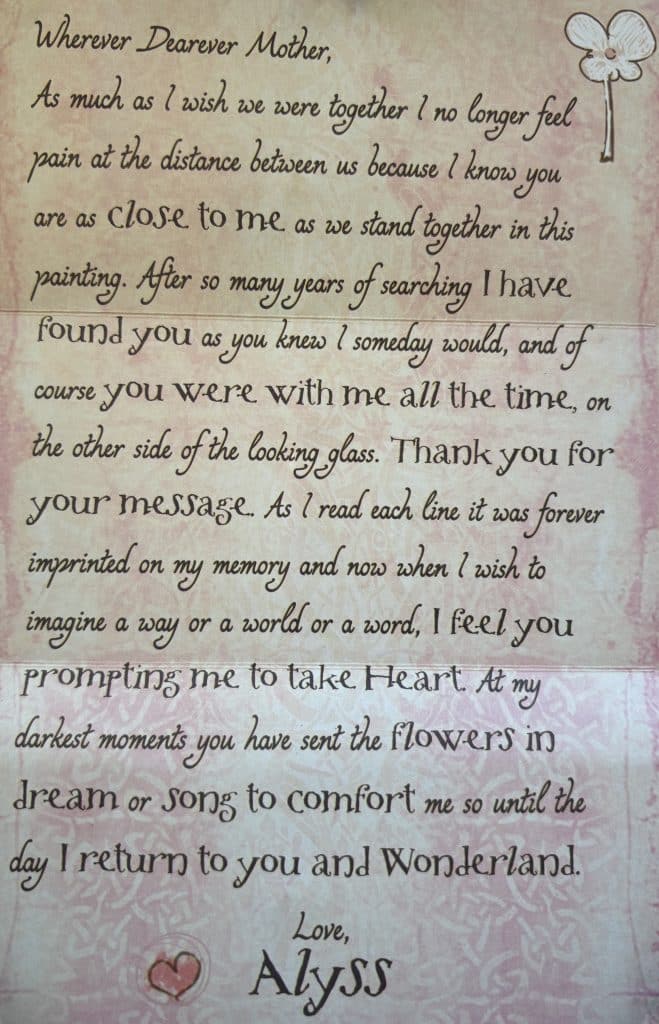

When mother ordered Royal Bodyguard Hatter Madigan to take me away from Wonderland I begged her to let me stay. Her last words to me were “No matter what happens, I will always be near you, sweetheart. On the other side of the looking glass. And never forget who you are, do you understand?” Since arriving in this world I have spent much of my life staring into looking glasses and hoping to see my mother but it wasn't until my powers of Imagination began to increase that I finally understood what she had meant. I must first IMAGINE that I see her. Trembling and nervous, I approached the looking glass and imagined my mother smiling back at me, within moments a message appeared!

Aces, Spades, Diamonds and Hearts

Lost their princess off the charts

Your Majesty's subjects await your return

So the light of imagination can continue to burn.

Someday, sweet daughter, you'll find your way home,

Hurtling out of this mundane realm,

Even though I cannot tell you how far,

A way can be found if you remember who you are,

Regal destiny is yours to win

Take Heart and always remember to….Imagine.

Agnes MacKenzie

Fascinating! What Alyss describes is an advanced form of 'mirror scrying' or receiving messages from other realms by images that form in your mirror. Known to every culture, 'magic mirrors' were used throughout history to enable one to see the present, the past, and the future. But the mind boggles at the concept of having a personal message written in such a lyrical manner suddenly appear in a looking glass. Some may question the authenticity of the message, but if not Queen Genevieve, who else would have sent this message of hope to a long-lost daughter? I wonder what messages await me in my own looking glass should my Imagination ever grow strong enough to see them.

Diary Entry - Undated

Today upon waking I realized that I no longer cared about Lewis Carroll's book or what others believe to be true and that all that matters is what I believe. As soon as this thought flashed through my mind I felt incredibly confident and decided to go puddle hunting. Towards late afternoon, I saw IT, shimmering in the center of Queen's Lane, a puddle where no puddle should be! I am certain that, this is the puddle that will take me home to Wonderland. I will always remember my mother’s words: “You will be the strongest Queen yet. Your Imagination will be the crowning achievement of the Land.”

Go back and read Parts One, Two, and Three of Alyss' Letters to discover how the Princess of Wonderland adjusted to her rude awakening on Earth.